3 black Philadelphians whose statues should replace Frank Rizzo | Opinion

As Philadelphia begins the healing process, we must ensure future memorials reflect the city’s diversity and tell a more complete story.

When I moved to Philadelphia, Frank Rizzo had been dead for nearly two decades. Still, black Philadelphians spoke about him with a passion and anger that was visceral. Rizzo’s legacy includes the untreated trauma that he inflicted on the African American community.

The Rizzo monument represents Philadelphia’s discredited past. The former mayor and police commissioner was sued by the U.S. Department of Justice for a pattern of police brutality that shocks the conscience. The Rizzo statue symbolized the cronyism and unaccountability that undermine trust in city government.

His statue at the gateway to municipal services sent a clear message: Black lives don’t matter.

For years, African Americans and allies peacefully called for the removal of the Rizzo statue. Paula Peebles, chair of the Pennsylvania state chapter of the National Action Network, has been on the front line. In an email, Peebles wrote: “From its installation on City property in 1999, the anchored image of Frank L. Rizzo was opposed. We have endured this painful reminder of Rizzo’s reign of terror and the pain he inflicted upon black people in Philadelphia. This statue never enjoyed the support of the majority of the people. It is because of our relentless pursuit to remove this villain that we can celebrate.”

On Wednesday, under the cover of darkness, the Rizzo statue was removed from its place across from City Hall. This move came following days of peaceful marches and violent unrest that have spread across Philadelphia and around the country, provoked by the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police.

As the city rebuilds, the quest for justice and true equity for all Philadelphia residents must inform public policies — including the acquisition of public art.

The black presence in Philadelphia dates back to 1639, but the first memorial dedicated to a specific African American was not unveiled until 2017, the Octavius V. Catto Memorial: A Quest for Parity. So let me suggest three Philadelphians who are worthy of memorialization.

» READ MORE: Live coverage of what's happening Thursday, June 4

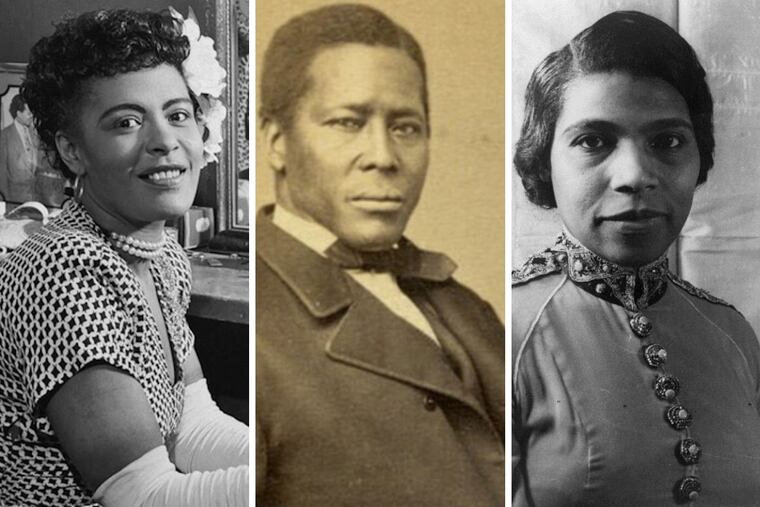

Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson was the first African American soloist to perform with the New York Metropolitan Opera. Her historic concert at the Lincoln Memorial inspired a generation of civil rights activists, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Given the current status with which Philadelphia is dealing, now more than ever before we need a source of hope, peace, equality, and love. There could be no greater symbol of all of those things than that of a statue of Marian Anderson,” Jillian Patricia Pirtle, CEO of the National Marian Anderson Museum and Historical Society, told me. “Everything that Marian Anderson stood for, believed in, and represented is an example of positivity, pride, and inclusion, not hate and division.”

Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday was born at Philadelphia General Hospital. She sang about the lynching of black men whose bodies were “fruit for the crows to pluck.” In 1999, the same year the Rizzo statue was unveiled, Time magazine named “Strange Fruit” a song of the century. The iconic jazz singer was harassed by Philadelphia police, including Rizzo and Vice Squad Capt. Clarence Ferguson. In 1939, Holiday told the world black lives matter. It would be poetic justice to have a memorial to Lady Day grace Thomas Paine Plaza.

William Still

William Still was secretary of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and a conductor on the Underground Railroad who helped hundreds of self-emancipated African Americans on their way to freedom. His journal, “The Underground Railroad,” published in 1872, breathes life into their stories and preserves the ancestors in public memory. As a result of the research of preservationists Oscar Beisert and J.M. Duffin, Still’s South Philly rowhouse where Harriet Tubman showed up on Dec. 29, 1854, is now listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. Like Catto, Still was involved in the campaign to desegregate Philadelphia’s railway cars.

Public art is about the power of public memory. Memorials tell the stories of a city’s past and values. Public art can bring us together or tear us apart. As Philadelphia begins the healing process, we must ensure future memorials reflect the city’s diversity and tell a more complete story.

Faye M. Anderson is the director of All That Philly Jazz, a place-based public history project that is documenting and contextualizing Philadelphia’s golden age of jazz. She leads walking tours of Green Book sites in Center City and South Philly.