Saving Philly’s endangered history, one building at a time | Opinion

The heart of the city's new approach is a citywide survey of historic buildings and a regulatory delay on issuing demolition permits for significant buildings not listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places.

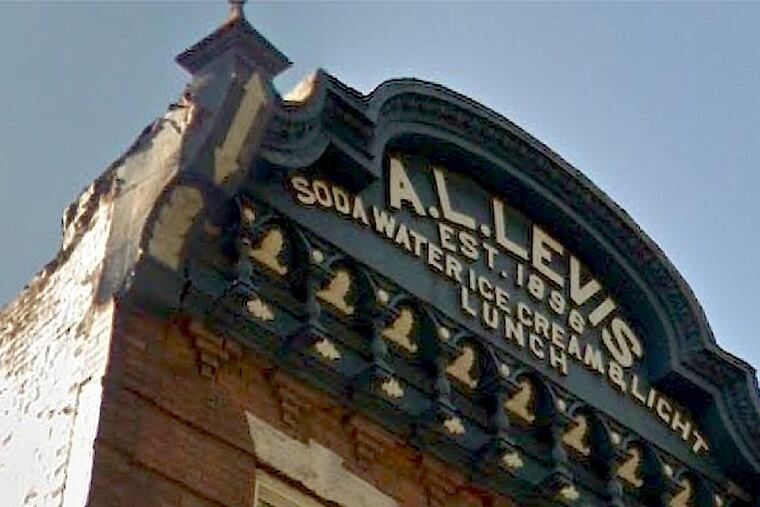

Abe Levis, a Lithuanian Jew, fled conscription into the czar’s army and opened his luncheonette in 1896 on Sixth Street above South, facing the new Starr Garden Playground. Surrounded by synagogues, event halls, movie houses, cigar factories, Yiddish theaters, collectivist libraries, and immigrant-owned stores of every possible kind, Levis became famous for fish cakes and hot dogs. By the time I moved into the neighborhood in 1997, Levis was gone, but its legend remained in the giant cornice sign advertising the famous hot dogs, a reminder of a city once defined by the exuberance of its public commercial life, the buildings themselves imprinted, like pages of a living book.

Actually, as I discovered recently, the Levis sign said nothing about hot dogs but told a more interesting story. “A.L. LEVIS EST. 1896,” it read, “SODA WATER ICE CREAM & LIGHT LUNCH.” I corrected myself not by walking by the building but by searching on Google Streetview and sliding the timeline to October 2016. For the richly decorated facade of the building, deemed dangerous by L&I inspectors, was removed without public notice a year ago, replaced by a fully unimagined brick front with undersized windows (facing a park), and a simple box cornice. Like the Stars of David and the Hebrew writing chiseled off the former B’Nai Reuben Synagogue down the street and the completely demolished Protestant Episcopal Church L’Emmanuello on Christian Street built by Italian immigrants in 1891 as a replica of a beloved Dolomite chapel, the Levis facade and sign was a legible phrase of turn-of-the-century working-class immigrant life so easily erased.

These are the very kind of redactions that distort the meaning of the city’s story, leaving it incomprehensible and increasingly bland — and that Philadelphia’s feeble preservation apparatus, in the face of intensifying development pressure, has not only failed to stop but tacitly enabled. Now, after a nearly two-year planning process, the administration of Mayor Jim Kenney has announced regulatory measures that fall far short of what many preservationists believe is necessary but that, if implemented with purpose and backed by resources — a substantial “if” given the city’s recent track record — could shift what we save and why.

With legislation introduced in City Council to incentivize developers to preserve buildings rather than tear them down and a proposal to offer zoning bonuses for contributing to a historic preservation fund, the heart of the new approach is a citywide survey of historic buildings and a regulatory delay on issuing demolition permits for significant buildings not listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. A demolition delay is necessary because only about 2 percent of Philadelphia buildings are listed on the register, and therefore legally protected. All the rest — including the vast majority related to immigrant, African American, and working-class life, such as schools, sacred spaces, factories, meeting and union halls, theaters, and retail storefronts — can, at present, be demolished without recourse.

» READ MORE: Philadelphia’s preservation reform effort has lost its way | Inga Saffron

The demolition delay’s potential is thus to flag the kinds of buildings until quite recently forgotten by officials who have had little to say about and almost nothing to do with maintaining the architectural presence of working people. Why this is has much to do with preoccupations with architectural mastery, wealth, and events of historical importance. But it’s also because so many of these buildings, products of a century-long golden age, betray the wounds of deindustrialization and economic collapse of the 1960s through 1980s. Who wants to save a site of loss or pain? Hundreds of thousands of people left the city in those decades, effectively turning their backs on neighborhoods that were experiencing extreme racial and economic upheaval. In the downward spiral of late-1900s Philadelphia, places lost their value in the popular imagination, but “white” spaces now in the hands of black and brown people came to be seen as worthless.

The demolition delay can help steer the focus of the Philadelphia Historical Commission, the underfunded and often misguided agency responsible for designating properties, to becoming an active partner in neighborhood development. But only if, in managing the citywide historic buildings survey, it empowers residents and community-based organizations to collect the data and decide what matters. If successful, preservation will become a tool of democratic civic engagement rather than an obsession of a frustrated few. Preservation goals might be made to align with affordable housing, sustainability, and neighborhood resilience.

» READ MORE: What’s working - and what’s not - with Philadelphia historic preservation

Preservation advocates have sought a citywide survey for decades. In the meantime, hundreds of exceptional places, each a phrase of this city’s ongoing saga, have been blotted out and, frustratingly, rarely replaced with something better. Philadelphia continues to accept, as a bitter side effect of economic collapse, design and building materials of poverty evidenced in the sad-sack replacement for A.L. Levis. This, too, is part of the saga — one we’re growing tired of hearing about.

Nathaniel Popkin is coauthor, with Joseph Elliott and Peter Woodall, of “Philadelphia: Finding the Hidden City” and author of the forthcoming novel “The Year of the Return.”