Amid the richly deserved kudos for Jim Gardner, who retired last month after 46 years as the anchor of 6abc’s Action News, one significant archival clip was missing: footage of his 1991 trip to his Jewish grandmother’s homeland of Lithuania, which the station telecast to highlight the Baltic republic’s secession from the soon-to-be-dissolved Soviet Union.

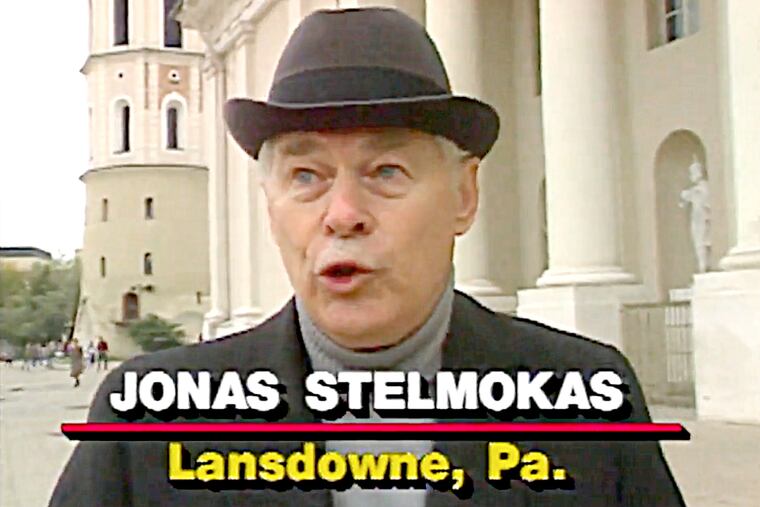

You might expect this emotional chronicle from three decades ago to have resurfaced in celebrating Gardner. But his reports from Vilnius were not publicly released. That’s because, unbeknownst to Gardner at the time, Jonas Stelmokas, the retired Lansdowne architect who excitedly showed him around Lithuania’s largest city, was a Nazi war criminal.

As I reported in The Inquirer in June 1992 — seven months after the station aired the story of its anchor’s visit — the U.S. Justice Department alleged that Stelmokas, then 75, had been a platoon commander in a volunteer unit that helped the Germans murder Lithuanian Jews in 1941 and 1942 and enforced their confinement in a Nazi-created ghetto in Kaunas (formerly known as Kovno), where approximately 32,000 Jews were killed.

Citing documents procured by the Simon Wiesenthal Center from newly accessible Lithuanian archives, I reported that Stelmokas was second-in-command of his battalion when it helped the Germans kill 1,522 Jews in two days at three villages outside Kaunas in September 1941. Stelmokas appears in a four-minute report that aired on Nov. 1, 1991, which WPVI shared with The Inquirer for this story.

Gardner’s excellent TV reports from Lithuania were part of a series surrounding the fall of the Soviet Union, mostly reported from Russia. The station had sent him from Moscow to meet Stelmokas in Vilnius because he had appeared on 6abc previously as a longtime leader in the Lithuanian American community in Philadelphia.

“We contacted him and made those arrangements,” recalled Steve Thode, 66, who produced the series. “He struck me as a passionate lover of Lithuania. He was a known, respected leader in that community. He had a certain energy. He was pleasant, a neat dresser, cared about his appearance.”

But appearances aren’t everything, and documents showed that the dapper architect also had been an architect of death.

In a complaint filed in federal court in Philadelphia in 1992, the Justice Department said that Stelmokas in his mid-20s had “advocated, assisted, participated or acquiesced in the murder and other persecution of Jews and other unarmed civilians in Lithuania.” Alleging that he’d concealed information and misrepresented his background when he applied for a U.S. visa in 1949 and when he applied for citizenship in 1954, the feds moved to revoke his citizenship.

Stelmokas denied the allegations, saying they were fabricated by the Soviet KGB. But in 1995, he was stripped of his citizenship when U.S. District Judge Jan E. DuBois ruled he had lied about his wartime activities to enter the country. The judge concluded that Stelmokas had been on duty in Kaunas on Oct. 29, 1941, when his battalion participated in the murder of 9,200 Jews — half of them children — in a single day.

A federal appeals court upheld DuBois’ decision, and in April 1998, a U.S. immigration judge ordered Stelmokas deported to Lithuania. He remained in the U.S., dying of a stroke in a Broomall nursing home that November at age 82, and is buried in Drexel Hill.

Friday is International Holocaust Remembrance Day. With only a few survivors left, distorters have become emboldened to influence young Americans whose knowledge about the Nazi genocide was already woefully scant. A nationwide survey of millennials and Gen Z released in 2020 found that 63% of those surveyed did not know that six million Jews were murdered, and 48% could not name one of the more than 40,000 Nazi camps and ghettos.

That’s why dredging up this sordid story is important — as a reminder that even the most astute among us can be fooled, and that some perpetrators of Nazi genocide lived in freedom in the United States with no remorse or sanction. Stelmokas thrived professionally in Philadelphia and lived comfortably in the suburbs because he had lied about his past.

Recalling this now is not intended to embarrass Gardner. In fact, the anchor and his station also reported the government’s case against Stelmokas.

Gardner himself has a visceral understanding of the value of vigilance. In an interview this month, he told me he felt he’d been hoodwinked by Stelmokas.

“I almost felt shame,” said Gardner, 74. “We certainly made him seem like what everybody else saw him as, a Lithuanian American patriot. This was his return home, it was almost heroic, certainly emotional. And to find out seven months hence the allegations that he was responsible for the deaths of Jews during the Holocaust was horrifying to me. I felt that I had been played as a sucker.”

On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, we must acknowledge that remembrance includes an obligation to learn the truth and to expose the lies, no matter how uncomfortable. We owe it to the victims.

David Lee Preston, a retired Inquirer editor, is a son of Holocaust survivors. Follow his work at www.DavidLeePreston.com