Nazis murdered my great-uncle in a forgotten massacre. Decades later, the few memories are fading. | Opinion

On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Abraham Gutman is haunted by the possibility that the little he knows about his relatives that died in the Holocaust is all that there’s left to know.

I don’t remember when I first heard the story, but I know that when he was a child, my father fantasized about befriending his Uncle Mishka.

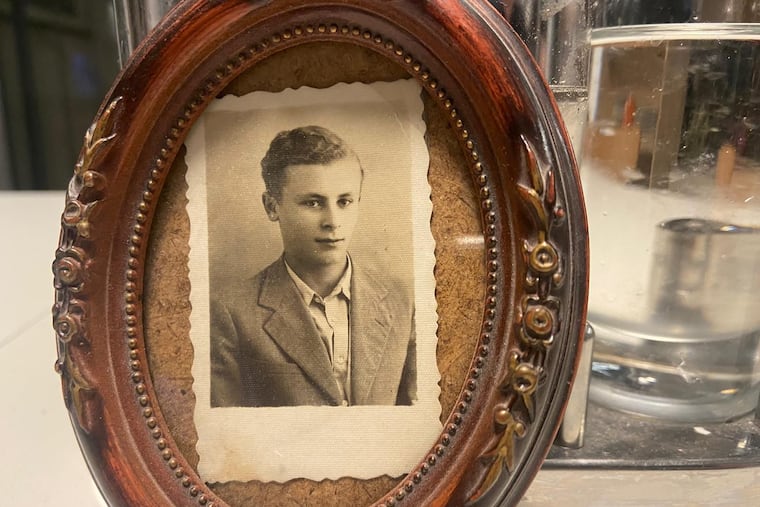

Like many kids in Israel in the 1960s, my father had few extended family members. Most were murdered by the Nazis. Mishka, his mother’s baby brother, died in his late teens or early 20s. But my grandmother had a photo of Mishka as a teenager. He was blond, hair neatly combed, with smooth cheeks that hadn’t yet grown a beard.

Time, for a child, exists in a different way than it does in adulthood — and for my father, Mishka remained young forever. He fantasized that Mishka survived the Holocaust. One day, he hoped, the teenager from the photo would walk through the front door into their Tel Aviv apartment.

I grew up in Tel Aviv and visited that apartment for Shabbat dinners. I had seen Mishka’s photo in my grandmother’s house, but I barely knew a thing about the brother she lost.

» READ MORE: EU honors camp survivor as world remembers Holocaust

We pieced together bits and pieces, mainly from rumors: My paternal grandmother, Mara, lost her baby brother, Mishka, and mother in an area that today is part of western Ukraine. My paternal grandfather, my namesake, lost his parents and three siblings. My grandfather’s elder sister died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, his father and brother died in a forced-labor camp, and his mother and baby brother died at Auschwitz. On my father’s side of the family we have these educated guesses, but on my mother’s side we know nothing.

From all the relatives I lost, Mishka stuck with me. As an adult, I’m haunted by the fact that, in all likelihood, the little I know about him is all that there’s left to know.

Like so many Jews, Roma, Armenians, Darfuri, Cambodians, Tutsi — or any other people who at one point in the last century or so someone tried to annihilate — genocide robbed me of my extended family members. It’s not just their deaths that haunt me, but also the loss of traditions, recipes, thoughts, and heirlooms.

As I think about how I will tell my children the story of their ancestors, I realize that the pain of being robbed of these memories is a family heirloom in itself, a loss that is passed between generations.

‘Lucky’

There is very little that I actually know about Mishka Gamerman, my grandmother’s younger brother.

He was born in 1919 to Arye and Batia Gamerman in the city of Rovno, which was then a part of Poland and now is in Ukraine. He had an older sister, Mara, the namesake of my daughter, who was born in 1917 and immigrated to Israel in 1937. I know that Mishka’s father died in the early 1930s. I know that he graduated from Tarbut Gymnasium, a regional hub for Hebrew and Zionist education, in 1936.

I know that my grandmother had a good life in Tel Aviv until her death in 2006 and that she hated Rovno.

My father remembers hearing that Mishka was gifted in math and studied at Lviv Polytechnic, a university that still exists in Ukraine. His acceptance was a big deal at the time — the Polish government had quotas limiting the number of Jewish students.

That’s it. An entire life, summarized in a few sentences.

No one knows how Mishka died. There are two legends in the family, depending on whom you ask.

My father remembers Mara telling him that after the war, a stranger from Rovno found her in Tel Aviv and said that during the Nazi occupation, a bomb hit the Gamerman house, killing Mishka and his mother instantly. My cousin Uri remembers Mara saying that the man told her that Batia and Mishka died in the Rovno Ghetto around 1942. A brief written testimony from 1958 to Yad Vashem, the Jerusalem-based Holocaust museum and research center, also claims that they died in the ghetto.

Mara chose to believe the bomb version. I hope that’s the true story. Most of the Jews of Rovno had a much crueler fate.

In both tellings of the same story, the man from Rovno added: “They were lucky they didn’t go in the woods.”

» READ MORE: Holocaust survivor from Philadelphia area takes one last trip to Auschwitz

A forgotten massacre

On Nov. 6, 1941, a few months after the Nazi occupation of the area, posters appeared all over Jewish neighborhoods of Rovno instructing Jews without work permits to report to the town square the following morning.

About 23,500 Jews, including 6,000 children, arrived the next day, carrying luggage. But the trip itself was short. The Nazis and their Ukrainian collaborators marched the Jews to Sosenki Forest — a pine grove near the city. Bystanders later testified that the Jews walked quietly as bullets from Nazis’ Tommy guns pierced the freezing air.

The least graphic description of what happened in Sosenki is that Jews arrived, undressed, and were thrown into a pit. Some were shot and others were simply left to die, their bodies crushed beneath their loved ones and neighbors.

Jeffrey Burds, the author of Holocaust in Rovno: The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941, described those three days simply as: “an Armageddon.” By the night of Nov. 9, 1941, some 80% of Rovno’s Jews were dead in two mass burial sites.

A whole community, gone.

Last summer I learned that Mishka and Batia were probably not so “lucky” after all. I couldn’t sleep one night so, again, I searched through the digital files of Yad Vashem’s archive. I came across two documents in Ukrainian, both listing Jews murdered in Sosenki Forest on November 1941.

My blood froze. Both of the lists included names I knew: Mikhael (Mishka) and Basya (Batia) Gamerman.

Did Mishka walk quietly? Was he separated from his mother? Or were they together until the bitter end?

Grasping for Mishka

When my son was born last fall, my obsession with Mishka intensified. I woke up to feed baby Max and my mind would race, thinking of ways to find any new information. I called my dad in the morning, asking him to repeat the little we know.

I want to know what kind of person he was. Why did he stay in Poland when his sister and classmates left? What were his politics and attitudes toward Zionism?

Last fall, I sent an email to Lviv Polytechnic and to a Ukrainian government archive, where some university documents from the era are stored. Neither had any record of my great-uncle.

Next I read A Tale of Love and Darkness, a book by the Israeli author Amos Oz that included details about Rovno. In one chapter, Oz references a memorial book that was published by surviving alumni of the high school that Mishka attended.

I tracked down the memorial book and made lists of names of students who might have known him. I reached out via email and LinkedIn messages to the children and grandchildren of his few classmates who survived the Holocaust. I sent them the class photo.

In a phone conversation, the son of one of Mishka’s classmates told me that he had never seen his father as a teenager before. Like my grandparents, their loved ones from Rovno didn’t like to talk about the old country. It was simply too painful.

Years after, for me, the pain comes from memories that I don’t have. Anytime I think about telling my children about Mishka, I feel trapped. I wish I could tell them more, but they will know that he lived.