Financial institutions should repair their trust gap with Black communities | Opinion

Partnerships with existing community organizations, and taking responsibility for racist practices like predatory lending, are a start.

Amid a pandemic that has brought Black Americans’ distrust of medical systems to the forefront, another source of distrust with acute consequences persists: financial institutions.

As has been well-documented, the ongoing economic crisis has disproportionately impacted Black Americans, who have faced higher rates of unemployment, job loss, and financial insecurity. A banner year for the stock market has exacerbated racial disparities in wealth, underscoring that differences in employment and income do not fully account for related inequalities.

Survey data from the Federal Reserve consistently shows that Black households on average hold less in the stock market than white households. In 2019, the median stock holding for a Black household was less than a third of a white household. This chasm corresponds with larger trends in the income gap and the ability of Black households to save.

Long-term data also reveals that Black households tend to invest less in stocks — by about half as much. This holds true for college-educated Black Americans. And where available, households of color also opt into employer-sponsored retirement plans less often.

Saving and investing are of paramount importance for building wealth over time, planning for retirement, and, eventually, passing on inheritance. Beyond raw numbers in assets, why does this dichotomy exist?

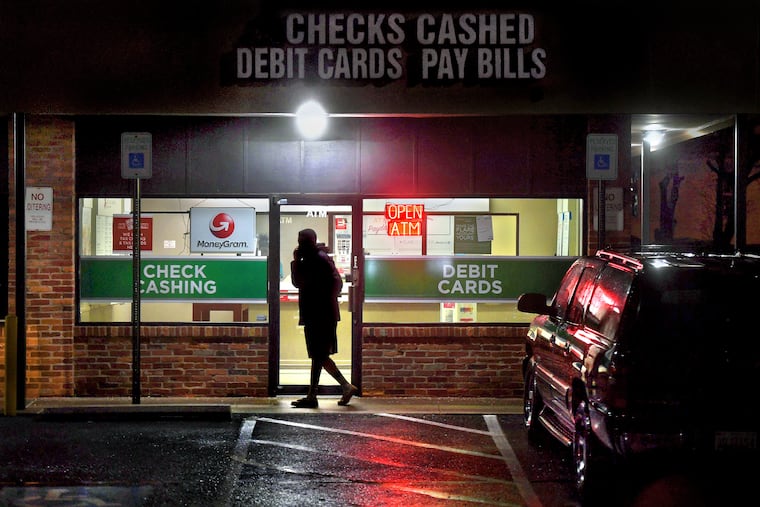

“There is a level of distrust for traditional financial services because of predatory lending practices,” explains Jason Ray, founder of Philadelphia-based Zenith Wealth Partners. Such practices include payday loans, where creditors provide short-term, high-interest loans (typically less than $500) to workers often waiting for their next paycheck. Hefty bank overdraft fees, Ray adds, which disproportionately impact people of color, don’t inspire much confidence, either.

During Black History Month, when Americans discuss the legacy of racism in this country, the legacy of Jim Crow, the legacy of slavery, we really do mean a continuing legacy, not just history: redlining, or location and race-based restrictions to financial services, leading to decades of disinvestment in certain neighborhoods. Rent discrimination (including by a former president). Exclusion from unions. These blows add up.

Philadelphia is hardly a stranger to these trends, as shown in a 2020 report from the City Controller’s Office. Historical redlining still impacts and impairs neighborhoods of color, many of which have the city’s highest incidences of poverty and homicide today.

If distrust plays a role in the wealth gap, how can we encourage healthy financial decision-making and market participation from Philadelphians who harbor doubts?

Recent pledges from local corporations, including Comcast and the 76ers, to support communities of color through charitable donations, advertising airspace, and a program to encourage buying from Black-owned businesses will help. Such objectives are of particular importance to Philadelphia’s Black-owned businesses, a number far too small that needs institutional support to grow. If these efforts are fruitful, trust in broader financial systems should follow. But that’s a big if.

“Corporations,” Ray argues, “need to coordinate with community-based organizations.” Charitable contributions need to be well-tracked and transparent. Most importantly? “Meeting people where they are.” That can be through youth organizations, churches, or local charitable foundations.

» READ MORE: Black Philadelphia renters face eviction at more than twice the rate of white renters

We need to make sure that pledges aren’t just pledges, that accountability matters. Money needs to stick, and outreach should be localized — $100 million only counts if the right people have access and, more importantly, have options for where to take their newly available resources.

Promoting financial literacy from the top down and strengthening ties between institutions and consumers can only go so far, however. Outreach efforts need to start from the bottom. Because the stakes are so high in financial planning, it helps to have members from communities who can address specific concerns and hesitations. Ray puts it plainly: “The advice industry is about trust.”

A member of the Association of African American Financial Advisors, Ray is part of another lopsided ratio. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, of the workers classified as “personal financial advisors” in the United States, white advisers outnumber Black advisers 10 to one.

Going forward, local financial institutions must move that needle by hiring people of color and reaching out to universities for representative recruitment. Philadelphia is a college town and a city with a majority of residents of color. This shouldn’t be so hard.

Matthew Jeffrey Vegari is a writer and economics researcher who previously worked for the City of Philadelphia as a policy associate.