Baseball’s Jackie Robinson Day does a disservice to the man it’s meant to honor

The major leagues have never fully acknowledged the ambivalence and internal conflict that Robinson faced while breaking the color line. That only diminishes his greatness.

We’re glad that Jackie Robinson Day is over.

While we enjoyed seeing Major League Baseball players wearing No. 42, we’ve had it up to here with MLB’s ritual of honoring Robinson on April 15, commemorating the day when he broke the color barrier in 1947. If we had our way, we would move the celebration back one week to mark the day when Robinson — as he himself would later acknowledge — felt like breaking something else.

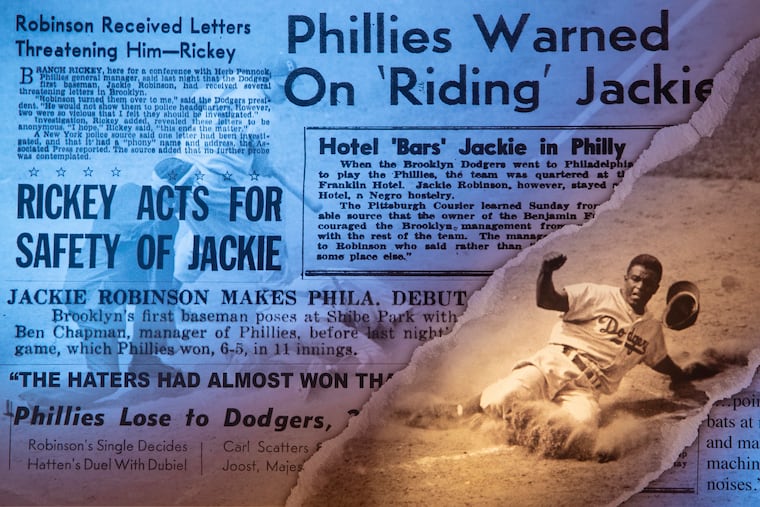

On the frigid afternoon of April 22, 1947, a torrent of abuse drenched Robinson as he walked to home plate for his first at-bat against the Philadelphia Phillies at Ebbets Field.

“Why don’t you go back to the cotton field where you belong?” someone shouted. Another yelled, “They’re waiting for you in the jungles, black boy!”

The vicious slurs were coming from the Phillies dugout, and the loudest voice belonged to manager Ben Chapman.

Robinson had heard racist insults throughout his life, but these felt unrelenting and intensely personal as Chapman and a handful of players shouted that Robinson had fat lips, a thick skull, and sexually transmittable sores.

Robinson simmered with rage. “I was, after all, a human being,” he later recalled.

He also desperately wanted to fight back. “For one wild and rage-crazed moment, I thought ... ‘To hell with the image of the patient black freak I was supposed to create,’” he wrote. “I would throw down my bat, stride over to the Phillies dugout, grab one of those white sons of bitches and smash his teeth in with my despised black fist.”

At his core, Jackie was really Jack Roosevelt Robinson, a fierce fighter who was intolerant of racial injustice and determined to smash every obstacle to the first-class citizenship he craved for himself, his family, and his people.

Unfortunately, Major League Baseball has always insisted on celebrating “the patient black freak,” the polite Jackie who smiled, turned the other cheek, and soldiered on nonviolently and courageously.

Robinson would no doubt understand baseball’s oversimplified treatment of his identity as another example of racist oppressors riding his back. Consider what he said in his 1972 biography, I Never Had It Made:

“I once put my freedom into mothballs for a season, accepted humiliation and physical hurt and derision and threats to my family in order to do my bit to make a lily white sport a truly American game,” Robinson wrote. “Many people approved of me for that kind of humility. For them, it was the appropriate posture for a black man.”

That’s the same posture that MLB celebrates every Jackie Robinson Day — “the patient black freak” who bent his back so other Black Americans might straighten theirs.

It’s time for Major League Baseball to change its ways and remember and honor Jack Roosevelt Robinson in three dimensions — both the poised champion of racial justice who endured indignities that no one should ever experience and, as he put it, the “human being” who in 1947 had to suppress the urge to use his “despised black fist” to smash the teeth of racist opponents.

Or the Robinson whose team’s 16-game winning streak in 1950 came to an end when he struck out on a third called strike. Robinson shook his head after the call. “That pitch was right down the middle,” said umpire Jocko Conlan. “My ass,” Robinson angrily replied — just before he was ejected.

Or the Robinson who, after another questionable call, this one in July 1952, booted his glove about 20 feet into the air. It was a strong, glorious kick, reminiscent of his days as a collegiate kicker for Pasadena Junior College and then UCLA.

Or the Robinson who in 1956 erupted after pitcher Lew Burdette of the Milwaukee Braves heckled him about his weight and the color of his skin. When Robinson later spotted Burdette in his team’s dugout, he fired a baseball directly at Burdette’s head. Lucky for the pitcher, Robinson missed, and the ball bounced off the back wall of the dugout.

“I threw it at him because I wanted to hit him right between the eyes,” Robinson later explained. “He was calling me names, and I won’t stand for that.”

None of us should stand for baseball’s whitewashing of Jackie Robinson Day. Failing to fully acknowledge the ambivalence and internal conflict that Robinson faced only serves to diminish one of the most remarkable moments in the struggle for civil and human rights in our nation’s history.

Yes, we grant that moving Jackie Robinson Day to April 22 might be asking too much. But politely asking Major League Baseball to present Robinson as “a human being,” rather than as “the patient black freak,” seems more than reasonable.

Yohuru Williams is the distinguished university chair, professor of history, and founding director of the Racial Justice Initiative at the University of St. Thomas. Michael G. Long most recently served as an associate professor of religious studies and peace and conflict studies at Elizabethtown College. They are the authors of “Call Him Jack: The Story of Jackie Robinson, Black Freedom Fighter.”