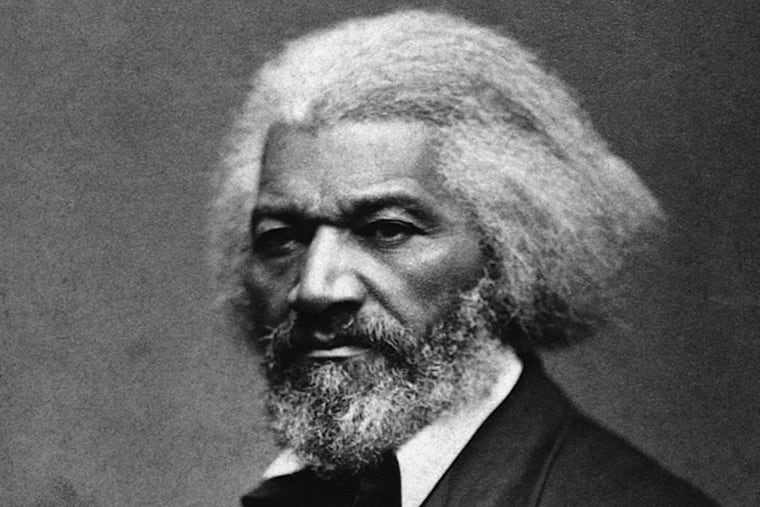

This July 4th, let’s honor Frederick Douglass and ‘agitate’

Instead of celebrating our flawed past and perilous present, let’s turn our focus to Frederick Douglass and the people who had the courage to fight for what was right.

“What to the slave is the Fourth of July?” asked Frederick Douglass in a speech at an Independence Day celebration in Rochester, N.Y., on July 5, 1852.

“Fellow citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? … The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

Of the 47 signers of the Declaration of Independence depicted in a famous painting hanging in the U.S. Capitol, 34 were slaveholders. The document declaring that “all men are created equal” was drafted by a slave owner, Thomas Jefferson, who fathered children with Sally Hemings, an enslaved Black woman.

Resistance to slavery is older than the republic. The first protest against slavery happened in Germantown in 1688. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was founded in 1775. Douglass’ clarion call for freedom was in that tradition.

On that fateful day in Rochester in 1852, Douglass told the crowd that, if he could reach the “nation’s ear,” he “would, today, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke.” It was a historic moment, and one that will be remembered long after we have forgotten the names of many of the men who signed the Declaration of Independence.

» READ MORE: ‘Frederick Douglass’: A reality as awe-inspiring as the myth

This wasn’t the first time Douglass had taken America to task. His Rochester comments were foreshadowed in a speech he gave on the grounds of the Pennsylvania State House, now Independence Hall in Philadelphia, just steps from where the Declaration of Independence was signed, in August 1844. While there is no transcript of his remarks, contemporary newspaper accounts reported that he delivered his now-famous “Slaveholder’s Sermon,” which parodied the belief that slavery was sanctioned by the Bible, and it was received “with enthusiastic applause.”

When the world comes to Philadelphia in 2026 to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, we should celebrate resistance as personified by Douglass, not just resistance to King George III.

Douglass’ presence in Philadelphia dates back to his escape from bondage. He arrived by steamboat from Wilmington in 1838. We can bring Frederick Douglass to life in Philadelphia by staging public readings of his most famous speech at places and sites associated with the abolitionist, including Independence Hall, Mother Bethel AME Church, Franklin Hall, the Union League of Philadelphia, and Camp William Penn, the largest Civil War training camp for Black soldiers, located in Cheltenham.

At the same time, we should heed the advice that Douglass gave a young Black American shortly before his death: “Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!”

“We should celebrate resistance as personified by Douglass, not just resistance to King George III.”

There is a precedent for agitation at 1776 commemorations. At the Bicentennial in 1976, the July 4th Coalition — made up of organizations representing Native Americans, African Americans, Puerto Ricans, women, LGBTQ people, and other civil rights agitators — staged a counterdemonstration. The objective was to hold a people’s alternative to government-sponsored celebrations. More than 30,000 people marched through North Philly and attended a rally in the Strawberry Mansion section of Fairmount Park.

Bringing diverse groups together to protest society’s inequalities and inequities is a fitting tribute to Douglass, who was about intersectionality before the term was coined. He attended the first women’s rights conference, the Seneca Falls Convention, held in July 1848, and signed the convention’s “Declaration of Sentiments,” modeled after the Declaration of Independence.

In an editorial published in his newspaper, the North Star, in the same month as the Seneca Falls Convention, Douglass wrote: “Many who have at last made the discovery that the Negroes have some rights as well as other members of the human family, have yet to be convinced that women are entitled to any.” But, as he noted: “Our doctrine is that ‘right is of no sex.’”

So this July 4, and every day after, let’s honor Douglass and agitate.

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s overturning Roe v. Wade, abortion-rights supporters are calling for the cancellation of 4th of July celebrations. I have a better idea: Instead of celebrating our flawed past and perilous present, let’s turn our focus to Frederick Douglass and the people who had the courage to fight for what was right, even when it often meant standing alone. That, more than barbecues or fireworks, represents the true meaning of freedom and Independence.

Faye Anderson is a public historian and director of All That Philly Jazz, a place-based public history project that is documenting and contextualizing Philadelphia’s golden age of jazz.