Racist U.S. history curriculums omit important stories of America’s First People | Opinion

In most states, social studies and history curricula provide little or no coverage of the important role Indigenous people have played in our national history and culture.

At the time of Columbus, anywhere from seven million to 15 million Indigenous people were living in the continental U.S. Over the following centuries, one million to four million or more were exterminated through war or diseases or forcibly assimilated into the dominant white culture. Along the way, the U.S. violated more than 500 treaties and stole 1.5 billion acres of Indigenous land.

Yet in most states, social studies and history curricula provide little or no coverage of the important role America’s First People have played in our national history and culture.

The erasure of the First People and their cultures has been so successful that a Reclaiming Native Truth survey found 40% of Americans believe we no longer exist.

But we do! The 2020 Census documented 9.7 million American Indians and Alaska Natives. Around 24% live mostly out of sight in 574 federally recognized nations or reservations or in 68 state-recognized tribes. Even more invisible are the 76% residing unnoticed in urban, suburban, and rural areas. All suffer from the systemic social and environmental injustice continuing to roil our nation.

» READ MORE: Photos of the Fifth Annual Indigenous Peoples’ Day at Shackamaxon

To get past the divisiveness and equity issues threatening our unity, we must realize that America is strong not despite its diversity but because of it. We can reach that moment by making our Native neighbors, their cultures, and their contributions visible. Unfortunately, we can’t do that until the heavily redacted American history taught in our schools gives way to a more complete and accurate account that tells the story of our nation’s original people.

This is slowly starting to happen.

Surveying 35 states with federally recognized tribes in 2019, the National Congress of American Indians found nearly 90% reported working to improve the quality of and access to a Native American curriculum in their schools. However, less than half said it was required and specific to tribal nations in their state.

So far, media coverage of Native-oriented education in public schools has focused mostly on states with the largest Indigenous population. (In 2020 the top six were Arizona, California, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Texas, and Minnesota.) Attention has also been given to education provided by federally recognized tribes and huge reservations like Pine Ridge.

Although this emphasis seems understandable, 644,000 Indigenous K-12 students live throughout the U.S. What’s more, 90% of them are enrolled in public school systems.

As acclaimed Native historian and educational activist Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz has pointed out, the dehumanizing myths and misconceptions that hurt Native American students flourish at the beginning of the school year. At this “loaded” time, all America celebrates the Indian-killing Christopher Columbus and attends sports events where over 900 Indian-named teams such as the World Series-winning Atlanta Braves attract war-whooping, “tomahawk-chopping” crowds. Then comes the iconic Thanksgiving holiday commemorating “the arrival of the religious Europeans who set the stage for Native American genocide.”

Dunbar-Ortiz urges educators to use November, which is Native American Heritage Month, to “discuss the reality of life, historical and current,” for the Native American students in our public schools.

» READ MORE: ‘We’re still here’: Native Nations Dance Theater continues its legacy during Native American Heritage Month

Indigenous children have a long history of being miseducated. From 1869 to the early 1980s, thousands were taken from their families and sent to an estimated 350 Indian boarding schools run by federal administrators and religious organizations. At their peak, these infamous schools were home to 60,000 children annually.

There they endured brutal mistreatment intended to “kill the Indian and save the man.” Many died from malnourishment, abuse, and disease and were buried in unmarked mass graves only now being unearthed.

When the U.S. passed laws to remove and relocate Indians so others could access their resource-rich lands, those who moved were promised benefits including education “in perpetuity.” That promise has been poorly kept.

In the 183 schools on 64 reservations in 23 states run by the Bureau of Indian Education, graduation numbers and test scores are the lowest in the nation.

The 90% of Indian students in public schools do not fare well, either. Lacking self-esteem and trust in the educational system, up to 36% of Native American students drop out of school, mostly between grades seven and 12. The rate is highest among those in cities, towns, and suburbs, where their culture is little known, and they are disciplined and suspended more than other students.

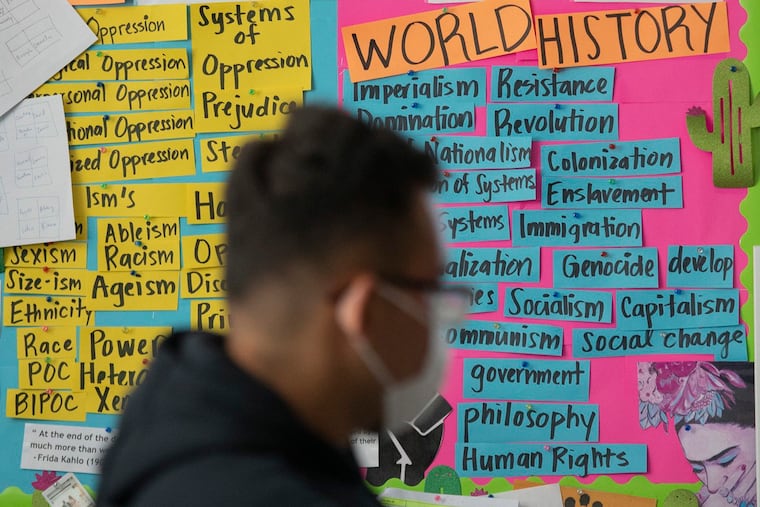

And the harm doesn’t stop there. The racism embedded in lessons that unfairly portray or even omit Native Americans fuels prejudice and discrimination among their classmates and in our society.

States such as Montana, Oregon, Connecticut, and North Dakota have tackled this issue by passing laws mandating that all students study social studies and history lessons that include Native America. As momentum builds, additional states are reviewing educational policies and standards, adding requirements, or expanding curricula.

For that, let’s all give thanks this November.

Carla Messinger is a Pennsylvania Lenape. A cultural consultant and preservationist, she directs Native American Heritage Programs. www.lenapeprograms.info