New Hampshire’s death penalty repeal: Which states are next? | Opinion

Pennsylvania is one of four states that has a governor-imposed moratorium on the death penalty but has yet to banish the punishment from its books.

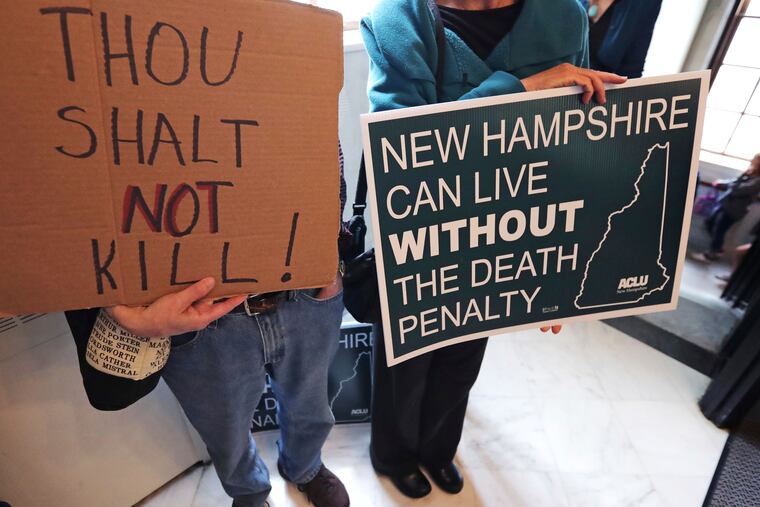

Well, New Hampshire finally did it. With a vote Thursday, the state Senate joined the House and overrode a veto by Gov. Chris Sununu and banned the death penalty.

So who’s next? Anyone?

Certainly not Alabama, which executed Christopher Lee Price Thursday afternoon, making him the third condemned prisoner to die there this year, and the second in the last two weeks. Price also was the eighth execution since Republican Kay Ivey became governor two years ago.

You remember Ivey, who the day before the last execution signed the nation’s most restrictive abortion law as she declared that “every life is a sacred gift from God” and that “we must give every person the best chance for a quality life and a promising future.”

Yeah, not so much on that “every life” bit.

New Hampshire’s override vote makes it the 21st state (plus the District of Columbia) to declare an outright ban on executions, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Another four states, including California and Pennsylvania, have declared a moratorium on the barbaric act, though that’s an impermanent solution.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced last month that he would grant a reprieve to all condemned prisoners for the duration of his governorship. But that doesn’t commit his successor to the same position.

And the 29 states that retain the death penalty don’t necessarily use it (the federal government and the U.S. military also have capital punishment, but rarely use it). Over the past decade, 11 states, including California, that have the death penalty have not executed anyone.

In fact, since 2010 there have been 310 executions in only 20 states, led far and away by Texas, with 114 executions, while five of those states recorded only single executions.

More broadly, executions have been in general decline since the 1990s, and in recent years an increasing number of conservative politicians — with an eye on false convictions and the overwhelming cost of the system — have joined efforts to repeal death penalties (Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty makes the case at conservativesconcerned.org).

It’s the perfect issue, in fact, for bipartisan cooperation, given the inability of the system to guarantee the innocent will not be executed, the disproportionate application to minorities and the poor, and the immorality of giving a government the power to kill its own people. It’s the ultimate in government overreach.

Not to mention arbitrariness in determining who might die — a 2013 report found that 2% of the nation’s counties have been responsible for a majority of death sentences since 1976.

So it’s not the nature of the crime that matters but in what county it occurred. A killing that might not draw the death penalty in Los Angeles County could draw it in Riverside County, even though the law applied is statewide.

As the Supreme Court has moved to the right with President Trump’s appointments, it has also embraced process over justice when it comes to capital punishment, signaling to death penalty abolitionists that their cause isn’t likely to get much help.

Which means the solution will have to be political, rather than judicial. Let’s hope that more states follow New Hampshire along that path.

Scott Martelle is a member of the editorial board at the Los Angeles Times, where a version of this piece originally appeared.