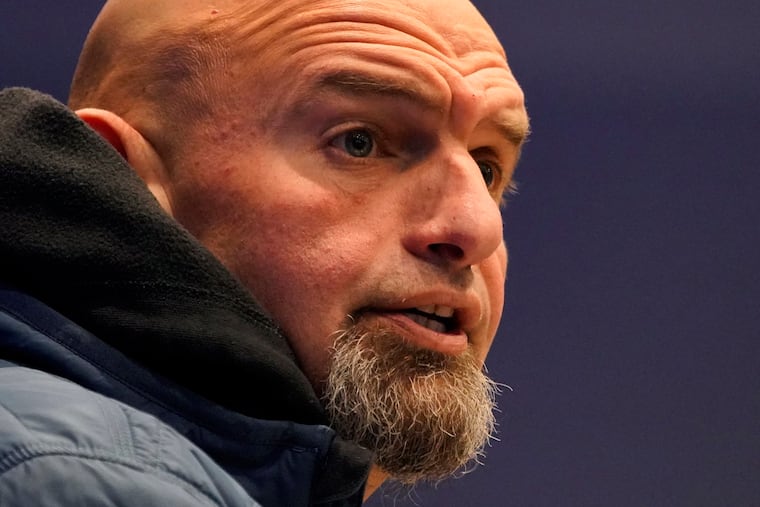

Oz-Fetterman debate discourse shows our ‘discomfort’ with disability

Some say that because John Fetterman needs accommodations, he is “not fit to serve.” This is a reflection of a larger problem: the persisting discomfort around disabled bodies and minds.

Tuesday’s debate between Mehmet Oz and John Fetterman — the first (and only) time the two candidates to represent Pennsylvania in the U.S. Senate will square off in public — will be closely watched.

Some viewers may notice an element that hasn’t appeared in previous debates: closed captioning.

Fetterman is recovering from a stroke and ensuing language disabilities, and relies on closed captioning as a result. Recently, the disability community and allies have voiced their utter disappointment at the way the public is talking about that.

Take, for instance, a recent NBC interview with Fetterman, in which the host spent a significant amount of time focusing on the need for closed captioning. Politicians, journalists, and others all had something to say. “Will Pennsylvanians be comfortable with someone representing them who had to conduct a TV interview this way?” asked CBS News correspondent Ed O’Keefe. “John Fetterman is simply not capable of doing this job,” proclaimed Rick Santorum, a former Pennsylvania senator.

The discourse can be summed up in one word: ableist.

It’s a reflection of a larger issue: our country’s persisting discomfort around disabled bodies and minds. In some ways, it’s not surprising, given the fact that we continue to see so few visible examples of people with disabilities integrated into everyday life.

The discourse can be summed up in one word: ableist.

The American with Disabilities Act, a 32-year-old piece of legislation, gave people with disabilities legal protections to do basic things that one takes for granted — traveling, eating inside restaurants, and applying for jobs without fear of overt discrimination. The road to that act was built on decades of advocacy, designed to counteract highly oppressive acts of eugenics, forced sterilization, institutionalization, and so-called “ugly laws,” which prevented “deformed” people from appearing in public.

Though legal protections have largely removed these overtly oppressive practices, the same perceptions of disability that propagated such practices unfortunately still seep into modern life.

Just look at how we are talking about John Fetterman.

The obsession over Fetterman’s need for basic accessibility software — closed captioning — harks back to the era of “ugly laws” and the exoticizing of disabled people, like the “freak shows” of yore. It is one more reminder of who dominates the narratives in our current society — nondisabled people — and the gross underrepresentation of disabled people and disabled experiences in nearly every sphere of society.

Only when able-bodied society sees disabled people doing the same jobs as them — with all their range of disabled experiences, variations, and technology — will our attitudes start to shift. And shift it must: People living with disabilities are the world’s largest minority.

The sobering fact about disability is that it can happen to any of us, at any point in our lives. But as long as disability is treated as a tragedy, something to be pitied or judged, true disability inclusion will not occur.

» READ MORE: Fetterman needs closed captioning. So what?

Pennsylvania is aging. By 2023, 1 in 5 residents will be older than 65, many of whom will have some sort of disability. We have to be proactive, and prepare for complete inclusion of people with disabilities in everyday life.

With the midterm elections approaching, pay attention to what candidates say — or don’t say — about disability. Only in recent races have politicians like Bernie Sanders started putting forward comprehensive disability policies.

One of the primary issues within disability activism is the right to live and work within the community. That will require more investment in home- and community-based services that enable people to live in their own homes. To help keep disabled people and the elderly away from nursing homes, Pennsylvania has to address the near poverty-line wages and almost nonexistent benefits for home-care workers, which lead to high turnover rates. The state has made some investments in community services for the disabled, along with limited wage increases for home-care workers, through the American Rescue Plan Act.

All disabled people have the right to be employed at inclusive workplaces and receive fair compensation. But in many states, including Pennsylvania, laws exist that allow employers to segregate disabled employees and pay them below minimum wage. Sen. Bob Casey, who has often been leading the charge with respect to disability policy, recently introduced a bill that would phase out these laws.

Other policies that our candidates should endorse include those that allow disabled people to work without risking the loss of basic needs through federal benefits, like the recently introduced SSI Saving Penalty Elimination Act, and the ABLE age-adjustment act.

Including people with disabilities helps everyone. Simple things like curb cuts for people in wheelchairs end up benefiting society, as they are also used by workers with heavy carts, people pushing strollers, and business travelers with rolling luggage, a phenomenon known as the “curb cut effect.” Sidewalks can be a matter of life or death. Our population is aging, and Social Security reserves are expiring. If we proactively integrate people with disabilities into the economy, everyone benefits.

I look forward to a day when disabled experiences and accommodations like closed captioning are not scrutinized and seen as a sign someone is “not capable of doing this job.”

Mihir Kakara is a neurologist, and an associate fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. @MihirKakara