Should Philadelphia have open primary elections? | Pro/Con

Pennsylvania is one of just nine states with closed primaries.

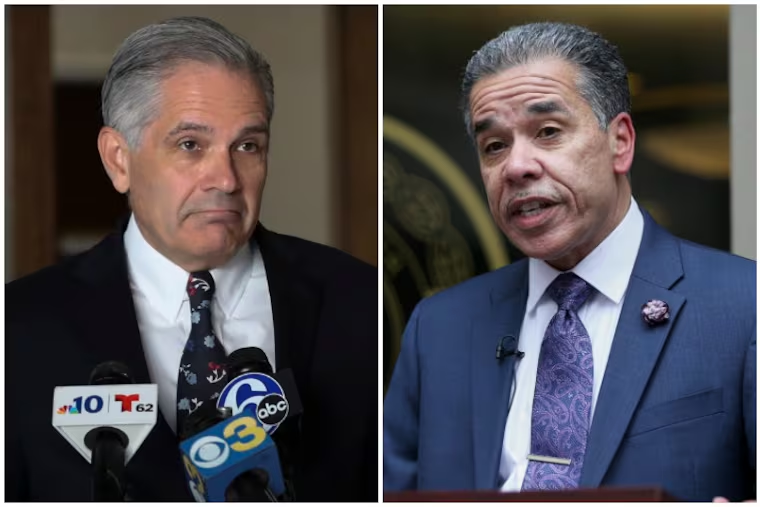

Pennsylvania’s next primary election is Tuesday, May 18, with statewide judicial and Philadelphia district attorney candidates on the ballot. Our state is one of just nine with closed primaries, meaning only registered Democrats and Republicans can weigh in on their respective partisan races, and independents just get a say on the ballot questions. State Rep. Chris Quinn (R., Delaware County) has introduced legislation to open primaries to the nearly 900,000 independent and nonpartisan voters in the state, but that wouldn’t open primaries for those already registered to a party.

» READ MORE: 2021 primary election: Endorsement guide

Some argue that primaries should be fully open for a democratic system, while critics counter that such an approach won’t lead to the strongest candidates to represent constituents. Two Inquirer opinion staff writers debate: Would Philly benefit from fully open primaries?

Yes: Everyone should get to vote in Philadelphia elections

Over 6,200 Philadelphia Republicans switched parties ahead of the district attorney’s race. While it’s hardly new to see otherwise staunchly Republican voters register as Democrats in order to vote in local elections, this year’s influx is bigger than ever, representing roughly two-thirds of Beth Grossman’s 2017 primary vote, per city data. While many progressive Philadelphians may see these voters as unwelcome party guests, the party switchers are behaving according to Philadelphia’s political reality: If you want a meaningful say in who governs you, who writes your laws, or who sits on the bench, you need to belong to the Democratic Party.

In the last 30 years of the city’s general elections, only 1999′s John F. Street vs. Sam Katz and their 2003 rematch have qualified as genuinely contested citywide contests. In the others, while the Republican Party may have been able to secure a candidate, they simply haven’t had the civic stature or funding to create a competitive race. This is not likely to change anytime soon.

» READ MORE: Philly Voter Guide: May 18, 2021

Is it really democratic to have an elections system where only the subset of society that belongs to the dominant party has a meaningful say in who wins? Is this process producing fair outcomes?

Defenders of the current system say that political primaries are private party events where outsiders shouldn’t have a voice. They would also note that antiurban sentiment emanating from conservative media and anti-Philadelphia rhetoric from Republicans in Harrisburg are driving forces behind the GOP’s marginalization in the city. That’s fair. But local Republicans aren’t exactly in a position to change any of that. There’s only one Philly Republican in Harrisburg, representing the farthest periphery of the city.

Even the Charter-designated seats for minority parties that are meant to serve as a voice for local Republicans have been lost to a faction of local progressives. Philadelphia’s at-large system had previously succeeded in offering city Republicans a roughly proportional voice in local government: three seats out of 17, or 17.6% of the seats on City Council, for a party that routinely takes about 17% of the vote. But Working Families Party member Kendra Brooks won one of the seats that typically goes to a Republican, leaving the City GOP with 2 for 17. Is it any surprise that, with potential to lose even this small voice, Republicans are taking another path to make themselves heard?

“In Philadelphia, this would mean that instead of just Democrats choosing our next DA, the entire city would be invited to decide.”

Of course, none of this would be necessary if Philadelphia used a system for local elections that included all voters regardless of party. In states as different as California and Georgia, voters can pick between all options, with the top two candidates going on to a runoff in which the entire electorate can choose between them. In Philadelphia, this would mean that instead of just Democrats choosing our next DA, the entire city would be invited to decide. Not only would this be more democratic for the city’s Republican, nonaffiliated, and third party voters — it would also ensure that citywide candidates actually secure a majority of the vote in the election that matters.

As things stand, candidates can win with less than 40% of the vote. In any self-professed democracy, let alone the cradle of liberty, it is important that all people have an equal chance to be heard, shape public policy, and elect representatives who can voice their concerns. Philadelphia Republicans are looking at a future where their only opportunity to do any of this is a general election that is a foregone conclusion. Philadelphia should find a system that enfranchises all of its citizens, not just its Democrats.

Daniel Pearson is a staff writer for The Inquirer’s opinion team.

No: Fully open primaries won’t select the best candidates.

It’s a bummer to be a Republican in Philadelphia. Chances are your vote won’t be the one that decides an election. Philadelphia is a one-party town: Since the city adopted the Home Rule Charter in 1951, no Republican has been elected mayor, and the last time Philadelphia had a Republican district City Council member who wasn’t Brian J. O’Neill was in 1990.

Philadelphia incumbents are very confident in reelection — no mayor has lost their bid since the charter. The city is also corrupt, with some pointing to party in-dealing as the reason. Is the solution to Philadelphia’s one-party rule problem as simple as: If you can’t beat them, join them in an open primary? Probably not.

Primaries are a party, not state, function — and there is value in that. In primaries for competitive general election races — such as the 2020 presidential Democratic primary — party members have a chance to vet candidates and ideas, and develop a bench of future candidates.

» READ MORE: Philly and Pittsburgh primaries are referendums on progressive politics | Opinion

Proponents of open primaries argue that, on the state level, closed primaries lead to more extreme candidates. But looking at Pennsylvania-wide elected officials — Tom Wolf, Bob Casey, Pat Toomey, Josh Shapiro — the word “extreme” doesn’t come to mind.

Another argument in favor of open primaries is that they will give an opportunity for Republicans to participate meaningfully in city elections. Maybe they would be able to tilt the balance toward candidates they prefer.

I do see the value of a partially open primary for unaffiliated voters, in which people who are independent can participate. That is a way to protect people’s privacy and include those who don’t support a party’s apparatus. But partisans should stay in their lane — or switch parties.

As a noncitizen who can’t vote, I get what it is like to feel left out of the process. But the last thing that politics needs is more incentive for voters to vote “strategically” instead of with their conscience. The decision inevitably will become: Who is the Democratic nominee that a Republican can most easily vote for?

That is a recipe for disaster. Philadelphia Republicans shouldn’t get to have an opportunity before the general election to act as spoilers. If there is a candidate that they deeply support in the Democratic primary, they should change their party registration — a relatively quick process that many chose to do this year.

“If local Republicans were willing to invest in this level of political organizing, maybe Philadelphia wouldn’t be a one-party town.”

The numbers also don’t really add up. In the 2019 primary, Mayor Jim Kenney won about 84,000 more votes than the Democratic runner-up, State Sen. Anthony Hardy Williams. The Republican on the ballot, Bill Ciancaglini, won 17,000 votes in his primary. To influence this election, nearly five times more Republican voters would have had to come out and vote — and all for Williams. In the low turnout 2017 Philadelphia DA race, one many Republicans would have loved to shift, the Republican on the ballot got 9,500 primary votes. Had Republicans coordinated to vote in unison for the Democratic candidate endorsed by the Fraternal Order of the Police, Rich Negrin, they would have had to persuade nearly 40,000 voters to show up, without a single one voting for another candidate.

If local Republicans were willing to invest in this level of political organizing, maybe Philadelphia wouldn’t be a one-party town.

But most fundamentally, if Republicans want to win power in Philadelphia, they should question the gap between their platform and the Philadelphia electorate. If the party continues to be anti-immigrant, anti-abortion, anti-gun control, or anti-trans rights, to name a few issues, they won’t win Philly elections no matter the system.

Abraham Gutman is a staff writer for The Inquirer’s opinion team.