No, a Phillies World Series win won’t lead to a recession (we think)

Is the Phillies World Series appearance a potential economic indicator? At a glance, the evidence for an oft-cited superstition is compelling.

Hours after Phillies slugger Bryce Harper launched a go-ahead eighth inning home run and calmly circled the bases Sunday, delivering another World Series appearance to Philadelphia, a superstitious observation started spreading across social media, and then leaped into financial commentary.

It went something like this: Every time a Philadelphia baseball team wins the World Series, financial catastrophe follows.

Get bonuses and free bets from our experts’ top sports betting apps

Were the Phillies in the World Series a potential recession indicator? At a glance, the evidence is compelling. The Phillies won the World Series in 2008, when many were feeling the pains of the Great Recession — and in 1980, which was followed by twin recessions. Back in 1929, the logic goes, the Philadelphia Athletics World Series victory begot Black Monday and the stock market crash.

As a former Wall Street Journal economics and energy reporter, and a longtime Phillies fan, I was intrigued. Would I be able to root for the Fightins without also playing a small role in hastening the coming of financial problems? I want to cheer them on without reservations and without feelings of complicity in and responsibility for unemployment numbers. I decided to investigate.

In the most recent reference, the timing doesn’t line up. The Phillies clinched the 2008 World Series on Oct. 29, yes — but that was more than a month after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. The National Bureau of Economic Research, the official arbiter of recession dating, determined the economy started contracting in December 2007. Also, did Chase Utley trade in collateralized debt obligations? Ryan Howard was all about home runs, not home loans. And while Charlie Manuel gets lots of credit for deft managing, he had nothing to do with loosening credit regulations.

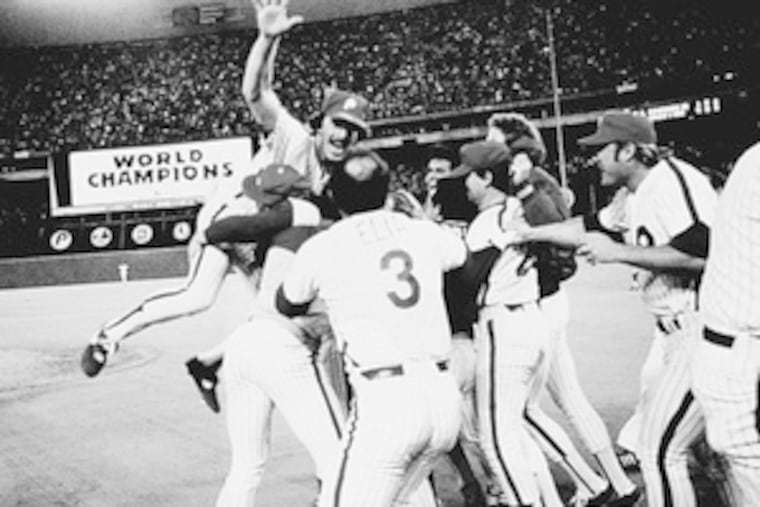

A generation earlier, the 1980 team won the title on Oct. 21. By then, a short-lived economic contraction (January to July of that year) had come and gone. By the time Tug McGraw jubilantly threw his hands in the air, the economy was growing again. These good times (both the healthy economy and dreams of a Phillies dynasty) were short lived. By July 1981, a much deeper recession was underway, one that would last for more than a year and send the unemployment rate up to 11%.

By then, we were in the middle of a new, strike-shortened baseball season. The Phillies started off well enough, but played below .500 ball after the stoppage, losing to the Montreal Expos in the playoffs. And the recession is generally attributed to efforts by the Federal Reserve to fight inflation, so unless Steve Carlton was secretly advising Fed Chair Paul Volcker on monetary policy, I just don’t see any connection here. And while Mike Schmidt had a great season (National League lead in home runs and runs batted in), he had inflated stats, not inflation-generating stats.

That leaves us with the 1929 Philadelphia Athletics. And here there seems like there is something in the water. The Athletics beat the Chicago Cubs in the World Series 4-1, winning the final game on Oct. 14. Two weeks later, the United States fell prey to the stock market plunge known as “Black Monday.” The good folks at the National Bureau of Economic Research said the recession began in August, two months before the Athletics’ victory.

Historians generally believe the protectionist trade policies in the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act deepened the economic damage of the Great Depression. Neither Smoot nor Hawley played for the Athletics. I checked. And the only protectionism practiced by Al Simmons, Jimmie Foxx, and the rest of the A’s lethal offensive lineup was protecting the strike zone.

The Athletics also left Philly in 1954, heading west for Kansas City and then California. We’re not responsible for them anymore. Pester Oakland.

So what’s the lesson here? You can absolutely root for the Phillies to win it all without worrying about the economic repercussions. Now, let’s talk about the fallout from the Astros winning the World Series in November 2017. Did you know that shortly afterward … Oh, never mind.

Russell Gold, a native Philadelphian, is a senior editor at Texas Monthly magazine and a third generation Phillies fan.