Before the Civil War, race riots hurt and silenced many Black residents. Philadelphia owes them the truth.

As a first step, the city can dispose of false notions about being a place of racial harmony at the time, and start telling the truth about its own history.

Philadelphia has yet to acknowledge or atone for the cruel and callous violence it inflicted upon its Black residents in the pre-Civil War era.

In a 20-year period between 1829 and 1849, the city’s Black community suffered a series of very brutal race riots that saw mobs of white people attack Black people in their homes, burn Black buildings to the ground, and beat Black people to death in the street.

Racial tensions in the city had been simmering for several years, fueled by white residents’ deep-seated disgust at having to compete with Black people for jobs, the Black community’s aspirations for social advancement, the increasing militancy of the abolition movement, and the waves of Black people migrating to Philadelphia from the South, especially formerly enslaved people.

Philadelphia’s hostility to the movement to end slavery immediately — known as the immediate abolition movement — was the root cause of a riot in 1829. Fanny D’Arusmont, an English social reformer and abolitionist, caused an uproar that summer when she gave a series of speeches in the city calling for freedom for enslaved people. Her lectures enraged a large segment of white Philadelphia society; on Nov. 22, their rage exploded into a riot.

Only a few years later, in the Flying Horses riot of 1834, at least 44 dwellings home to Black families were damaged or destroyed. The disturbance started as a series of minor racial incidents, including a fight on Aug. 8 between Black residents and white firemen from the Fairmount Engine Co. On Aug. 12, a mob of several hundred young white men, some armed with clubs, advanced to the Flying Horses, a tavern near Seventh and South Streets named after a popular carousel on the property, seeking revenge. The mob destroyed the carousel, demolished the tavern, and attacked any Black person found in the vicinity.

The following day, the mob launched an all-out assault. Rioters broke into the homes of Black Philadelphians, beat the inhabitants with clubs, destroyed their furniture, and pillaged their personal belongings.

The mob launched an all-out assault

The rampage lasted through Aug. 15.

Less than a year later, the 1835 riot was sparked by the beating of white attorney Robert R. Stewart by his Black servant. Hell-bent on collective punishment, a white mob numbering 1,500 people broke into a collection of Black-owned houses south of Catharine Street known as Red Row and assaulted any young Black man found inside.

One petrified Black man jumped from his roof to try to escape the rioters. The mob found his leap amusing, gave him a round of applause, and let him go free.

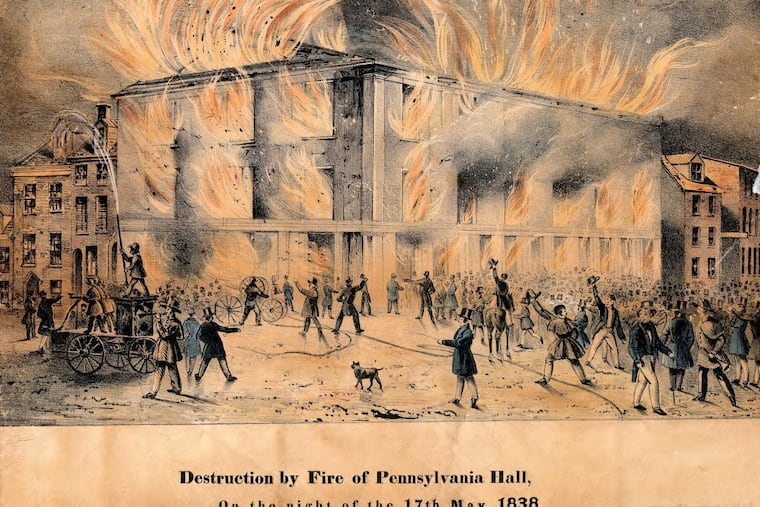

Perhaps the most well-known race riot in Philadelphia history, the 1838 riot is infamous for the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall. Built by abolitionists at Sixth and Haines Streets, the hall opened on May 14. Three days later, a pro-slavery mob burned it to the ground.

The first sign of trouble came on Pennsylvania Hall’s opening day, when a mob began to form outside and someone threw rocks through the windows.

On May 15, signs were discovered posted around the city calling on all citizens who respect “the right of property” to stop the hall proceedings, “forcibly if they must.” By nightfall on May 16, the mob had grown to around 3,000. On May 17, approximately 15,000 rioters broke down the hall doors and set it aflame. Firemen arrived on the scene, but instead of fighting the fire, they decided to let the fire burn.

The 1842 riots, known as the Lombard Street riots, began on Aug. 1, when Black people were marching in a parade marking the end of slavery in Jamaica. When a white mob began pelting them with projectiles, the marchers fought back, and the altercation erupted into a riot. Again, Black residents and their homes were targeted. Smith Hall, built by a wealthy Black man near Seventh and Lombard Streets to replace Pennsylvania Hall, was burned to the ground. So was the nearby Presbyterian church.

» READ MORE: How Haitian immigrants and local Black resistance helped subvert slavery in 18th-century Philadelphia | Opinion

A main target of the mob was the home of Black leader Robert Purvis, who oversaw Underground Railroad activity in the city. Purvis sat on a staircase in his home armed with guns while rioters lurked outside. Forced to flee to his country home in Bucks County, his absence temporarily brought Underground Railroad work in the city almost to a standstill.

The 1849 riot was kindled by one of the gravest crimes a Black man could commit in the 19th century: having consensual sex with a white woman. On Oct. 9, a white mob attacked a building where Benjamin Jackson, a Black man, lived with his white wife, first pelting it with stones. Around 9 p.m., rioters set the house on fire, which ended up burning several adjacent Black-owned buildings and businesses.

The wrath of these riots had a devastating effect on the city’s Black population. Hundreds of people were chased from the city, and most never returned. For a while, Black leaders, seemingly in shock, began to move away from provocative issues like abolition, before waking up and recommitting themselves to antislavery and civil rights.

Philadelphia must show remorse for its inhumane treatment of Black people in the antebellum period. As a first step, it can dispose of false notions about racial harmony in the North, and start telling the truth about its own history.

Greg Johnson is a writer and editor in Philadelphia and the creator of “The History of Black Philadelphia” Facebook page. He is working on a book about the history of Black people in Philadelphia. gjohnson41@outlook.com