Philly School District needs better data to achieve equity | Opinion

The district needs to strive toward “equity” of support, giving all students what they each need to be successful, vs. literal “equality,” giving everyone the same regardless of level of need.

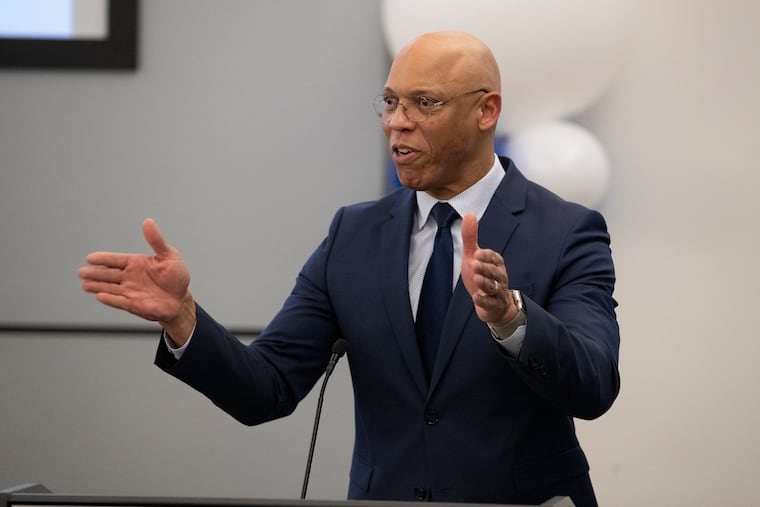

One of William R. Hite Jr.’s admirable anchor goals for the Philadelphia School District from 2019 is that “100% of 8-year-olds will read on or above grade level” because “every child deserves a high-quality education.”

Providing that high-quality education became harder this year, when the pandemic closed schools and disrupted students’ routines. Before that, as of the 2018-19 school year, the district had seen slight progress with the overall rate of reading proficiency at 33%, up from 30% in 2015-16. While any improvements are positive, it’s essential to examine how those improvements break down by individual schools to make clear where help is still needed most. If we look at the school-based data, we find that some schools have actually achieved as high as 86% proficiency, while others are as low as 15%.

Given the reality of funding limitations and severe budget cuts, the most effective way to meet student needs is to direct money, personnel, and time where they’re needed most. The goal needs to be “equity” of support, giving all students what they each need to be successful, vs. literal “equality,” giving everyone the same regardless of level of need.

Why is disparity among schools significant? The reality is that in order to achieve a district-wide goal like grade-level literacy, resources must target the individual schools with the lowest proficiency percentages.

It’s the same issue when it comes to school attendance. The district’s laudable attendance campaign led to an 8.5% increase in students attending at least 95% of instructional days in 2017-18 compared with the year before. But efforts must focus on where attendance rates remain lowest. This is particularly significant because school attendance is linked directly to achievement, with high absence rates resulting in learning gaps that are extremely difficult to fill.

Reducing school absenteeism is a cost-effective strategy for improving academic performance. This is especially true for students living in poverty, as they are the most likely to have had low attendance over multiple years, and the least likely to have the resources to make up for lost learning time. It makes sense to identify which schools are still having problems with attendance, to ensure that the attendance campaign directs resources appropriately.

To take this a step further, we should also look at how the percentage of 8-year-old children reading at grade level corresponds to the third-grade attendance rates at individual schools. Addressing these issues comprehensively is the best way to lead to improvement for every student.

Hite’s action plan rightfully proposes a system that identifies which students are at risk academically, and then provides interventions based on needs, going on to suggest that further work has to link the most appropriate interventions to the specific needs. Continuing this approach would help the district achieve equity of support, as assistance is tailored to each student.

» READ MORE: School District leaders: Maintain education funding for Philly students | Opinion

To follow through on its plan to “ensure that we are creating great schools in every neighborhood,” the district should target its support based on achievement and attendance data for individual schools, and then share with parents and communities exactly how they’re doing that and what happens as a result. They should be transparent about what types of resources they’re providing to help the lowest-performing schools and those with low attendance rates. This information should be provided in hard copy upon request, so families without internet access will be informed, too.

Pursuing true equity of support, and then reporting on the results, can help the Philadelphia School District live up to its assertion that “all students can achieve.”

Deanna Burney has been a teacher, counselor, principal, and assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction. She also served as a senior researcher at the Consortium for Policy Research in Education at the University of Pennsylvania.