NFL owes it to Philly football great Bert Bell to bring the Super Bowl to his hometown | Opinion

What if the city could marshal some of the same energy and enthusiasm that has gone into the World Cup effort, and point it toward another huge sports prize that would matter in Philadelphia?

In a civic-minded marriage of football and fútbol, the Eagles are now working with the city to bring a portion of soccer’s World Cup to Philadelphia in 2026. Getting a piece of the action would certainly be an enormous boon for the region.

The late Bert Bell, former NFL commissioner and a Philadelphian all the way, would surely wonder: Why stop there?

What if the city could marshal some of the same energy and enthusiasm that have gone into the World Cup effort, and point them toward another huge sports prize that would matter in Philadelphia? That prize, of course, would be to host a Super Bowl.

Philly has never hosted a Super Bowl and probably won’t any time soon. The last time the NFL title game came anywhere close to our region was 1960, when the Eagles handed Green Bay Packers head coach Vince Lombardi his only playoff defeat and won the league’s championship at Franklin Field. (That was the Birds’ last title until winning the Super Bowl — and the championship trophy now named for Lombardi — in 2018.)

These days, the NFL prefers to stage its annual championship game each February in a warmer city or indoors (though, hmmm, it was held outdoors in East Rutherford, N.J., in 2014 on a 49-degree day).

» READ MORE: Bring the 2026 World Cup to Philly — and world-class soccer facilities to neighborhoods | Editorial

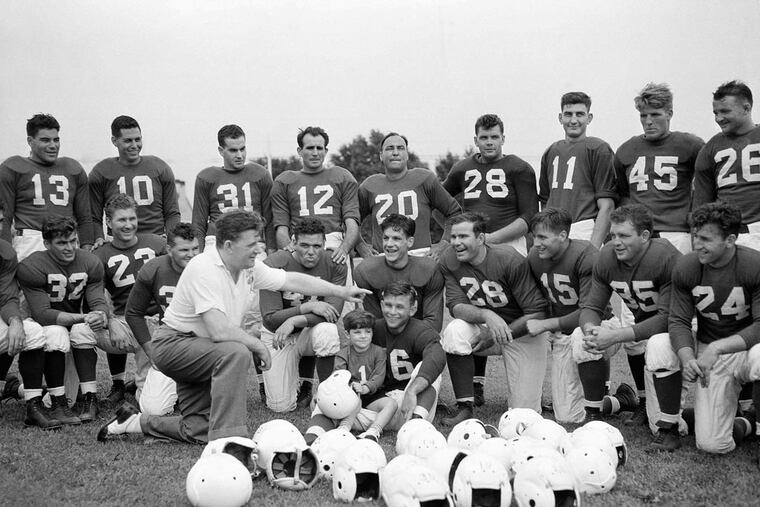

The NFL might have not survived, let alone thrived, without Bell, its commissioner from 1946 to 1959. Bell grew up here, played and coached football at Penn, and launched an NFL team in 1933 that he’d call the Eagles, after the National Recovery Administration logo.

Bell lived in Narberth and ran the NFL with authority from offices in Philadelphia. He conceived the NFL Draft to promote parity, and arranged the schedule, using dominoes in his bedroom, to keep bad teams in contention longer.

A year before Jackie Robinson became the first Black player in baseball’s big leagues in 1947, Bell oversaw the reintegration of the NFL with the Rams’ signing of Kenny Washington. Bell was pro-players’ union and was fiercely determined to keep gambling’s influence on the league at a minimum.

Bell’s biography, written in 2010 by the late Philadelphian Bob Lyons, was titled On Any Given Sunday because Bell often said that to convey the idea that his league was unpredictable and entertaining: that, on any given Sunday, any team could beat any other team.

Bert Bell, whose given first name was de Benneville, could deal with lousy weather, too. The Eagles were to play the Chicago Cardinals for the 1948 NFL championship at Shibe Park in North Philadelphia, which, on the morning of the game, was smothered by a blizzard.

The Cardinals called Bell and told him they’d voted not to play. “You’re playing,” Bell said, punching up the order with an expletive. This was the first game under a national radio contract negotiated by Bell. So the Cardinals and Eagles helped clear the snow from the field.

One of Bell’s two sons, Upton, remembers looking down at the snowy field from the press box at Shibe Park. He spotted his father, in a hat and brown coat, helping to pull off the frozen tarpaulin. The game started only a half-hour late, and the Eagles won, 7-0.

“He hated people to make a fuss over him,” Upton Bell, who is to turn 84 on Oct. 13, says over the phone from his home in Cambridge, Mass. “He didn’t like anything ostentatious.”

Bert Bell even died at a football game in Philadelphia — 62 years ago this week, on Sunday, Oct. 11, 1959, between the two NFL teams he’d owned, the Eagles and the Pittsburgh Steelers. Tommy McDonald had just scored a go-ahead touchdown for the Eagles.

Bell liked to change seats during games so he could mingle. There was a commotion in the stands behind one end zone at Franklin Field, and Upton Bell peered through binoculars at what was going on. A man in a brown suit was receiving medical attention. His father always wore a brown suit when it was warm, and a blue one when it was cold. It was his dad.

“There’s never been a day that goes by in my life that I don’t think about that ending,” Upton Bell says.

Bert Bell was taken two blocks to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, with friends and family trailing. (Upton says that Art Rooney, the late owner of the Steelers, was nearly sideswiped by a trolley.) Resuscitation of Bell, just 64, was futile. Upton claimed a money clip from his father’s trousers.

Prior to the game, a former Eagles player named John “Bull” Lipski spotted Bert Bell in the ticket office at Franklin Field and said he was down on his luck and needed to borrow money. Bell emptied his money clip, telling Lipski to call him the following day for more.

That was not so unusual. He gave out his home number, MOhawk 4-4400, to every player in the league. He was tough but beloved. Thousands went to his viewing in Philadelphia, and hundreds attended the funeral Mass at St. Margaret Roman Catholic Church in Narberth.

Bell is buried at Calvary Cemetery in West Conshohocken. His tombstone is unremarkable, with no acknowledgment that he once ran — and probably saved — the NFL. There is also a Pennsylvania historical marker for Bell near the Narberth train station.

Bell was one of the inaugural inductees into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963. Even though he lost thousands as an owner and compiled a 10-44-2 record in five years as coach, Bell was among the first inductees when the Eagles started an Honor Roll in 1987.

Upton Bell, who later became an NFL executive, remembers his brother, Bert Jr., answering the telephone before his father’s wake, when “everyone was still in a state of shock.” It was an official from Philadelphia National Bank, telling Bert Jr. the deal was off.

Wait. Deal?

Only then did the rest of the family learn that Bert Bell, who had been in poor health, planned to resign as NFL commissioner after the 1959 season and purchase the Eagles for $950,000 — the very franchise he bought with Lud Wray for $2,500 some 26 years earlier.

So who knows? The Eagles, who beat Lombardi’s Packers for the NFL title at Franklin Field a year after Bell’s fatal heart attack there, might still be in the Bell family.

The NFL needs to have its big game here at least once not just because Philadelphia is a great football town, but because Bert Bell helped make it that way. And if New York can have a Super Bowl outdoors in February, so can Philly.

Dave Caldwell grew up in Lancaster County, graduated from Temple University, and lives in Manayunk. He was a sports reporter for The Inquirer from 1986 to 1995.