I had polio in the 1950s. RFK Jr.’s vaccine policy proposals are dangerous.

Polio might seem like a disease of the distant past, but I know its dangers firsthand. To revoke governmental approval of the vaccine would pose a grave threat to public health.

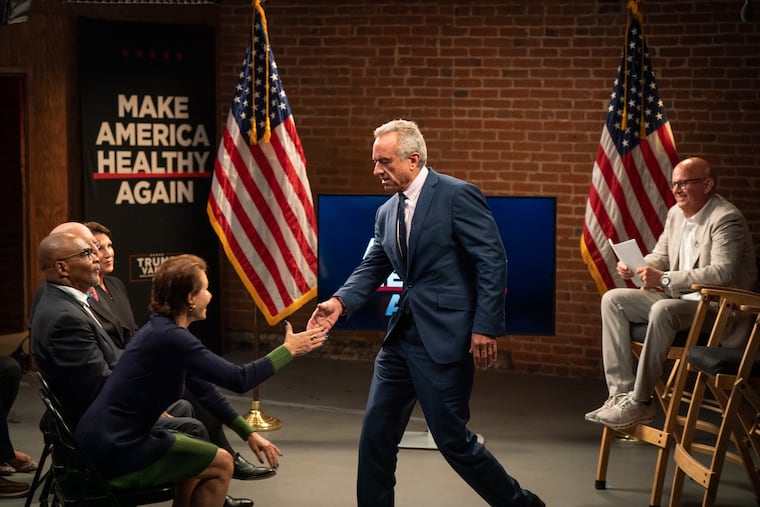

Earlier this month, news broke that a lawyer linked to Robert F. Kennedy Jr. — the incoming leader of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services — petitioned the government to revoke its approval of the polio vaccine.

Polio might seem like a disease of the distant past, but I know its dangers firsthand. To revoke governmental approval of the vaccine would pose a grave threat to public health.

In September 1954, I fell off my bicycle while riding home from school. When I got home, my mother put me to bed and called the doctor. When the doctor examined me, he immediately called an ambulance. I was taken to a hospital outside my hometown of Bristol, England.

A painful spinal tap revealed what the doctor had suspected: I had contracted polio. The Salk vaccine, which first arrived one year later in 1955, has helped prevent and mostly eradicate the illness, but there is still an enormous amount that is not known about the causes and origins of the illness, and there is no cure for it. The effects it has on the human body are severe, and in many cases, fatal.

The hospital where I was to spend almost three months was an isolation hospital. Every summer, it seemed, clusters of people (many of them children) would come down with the disease and be isolated, as I was. For the first few weeks, I shared a hospital room with another boy, even more paralyzed than I was (in my case, both arms and both legs).

My one overriding memory of those first few weeks is that next door to our room was another room where one of the hospital’s three iron lungs was installed. The machine made a constant humming noise as pressure was applied by the machine to the chest of the people inside it in the hope that their impaired breathing could be maintained. In a few cases, it worked, but in far too many, it did not, and the patients died. The wonderful nurses at the hospital tried to keep such information from us, but inevitably, the close proximity of the machine meant we found out.

As the number of young boys at the hospital increased to eight, the brave staff and nurses decided to create the “ward from hell” and put all eight boys, including me, into a single ward so that we could at least enjoy each other’s company. Thus, for the remainder of my time in the hospital — till early December — we all were clustered into a single room.

I can still vividly recall the day when two doctors and two nurses came over to my bed and told me to get up. They told me that, as far as they could tell, the disease had left me.

I was now hoisted out of bed and immediately collapsed on the floor. I had not used my legs for several months. I was then hoisted up again by the two nurses, one on each side, and told to take a step. I had to ask how I was supposed to do that, and the doctors replied that you put one foot in front of the other.

Thus began the long process in which I had to learn how to walk all over again. When my poor parents were finally allowed to visit me, they admitted later that they were horrified to see me strutting around proudly like a duck. Gradually, however, I was able to recover my normal walking style. In a personal boast here, I can record that it was one year later that I won the 100-yard dash at my school’s sports day — in 11.5 seconds!

The convalescence period was six months spent at home, although I was gradually allowed to venture outside for short periods. The one thing for which I am eternally grateful is that the doctors asked my parents what they proposed to do with a 12-year-old boy at home. “Was he musical?” they asked. When my mother informed them she was a ballet dancer and teacher, they said, “Piano lessons twice a week.” Thus began my second career as a keyboard player, firstly the piano and later the organ.

When I think back to those days in the hospital and the lengthy recovery process, I am still amazed at the way in which the Salk vaccine has been able basically to eradicate polio from the world, and thus put an end to the annual summer panic for parents that was a regular feature of life in Britain and other countries at that time.

I am equally amazed to realize that there are still some people, some families, who do not have their children immunized against polio, not realizing, I assume, the kind of lives that are still being led by those unfortunate people who have suffered from the disease and recovered, most of them with severe body impairments that I was spared — for reasons my doctors were unable to explain.

While I am, of course, forever grateful that such is the case, I am discomforted by the thought that of those eight boys in that single ward at the isolation hospital, I was the only one to walk out unaided.

It is with this background that I view the current vaccine controversies with dismay. In a country like Pakistan, polio is rampant because Islamic extremists have managed to convince enough people that the vaccine is a Western plot intended to sterilize children.

The polio vaccine arrived just one year too late for me, but as I reflect on my incredible good fortune, I can only express the hope that rationality will prevail and that our political leaders will continue to support vaccines.

Roger Allen was a professor of Arabic and comparative literature at the University of Pennsylvania for 43 years.