Local ‘reparations’ plans make promises they can’t keep | Opinion

The case against local so-called “reparations,” and in favor of a federal plan.

In the last few years, the term “reparations” has leaped from the fringe of American discourse to the mainstream. This happened in part thanks to the last presidential race, when Marianne Williamson recommended $100 billion to $500 billion in compensation and some of her fellow Democratic hopefuls agreed some form of restitution was justified.

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s highly visible murder, not only do reparations continue to be a topic under national consideration — municipalities are now racing to pilot their own “reparations” programs on behalf of African Americans. California and New York have created reparations commissions, and proposals have been floated in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Indeed, piecemeal “reparations” initiatives appear to be experiencing a spawning season.

» READ MORE: Despite racial reckoning, state efforts stall on reparations

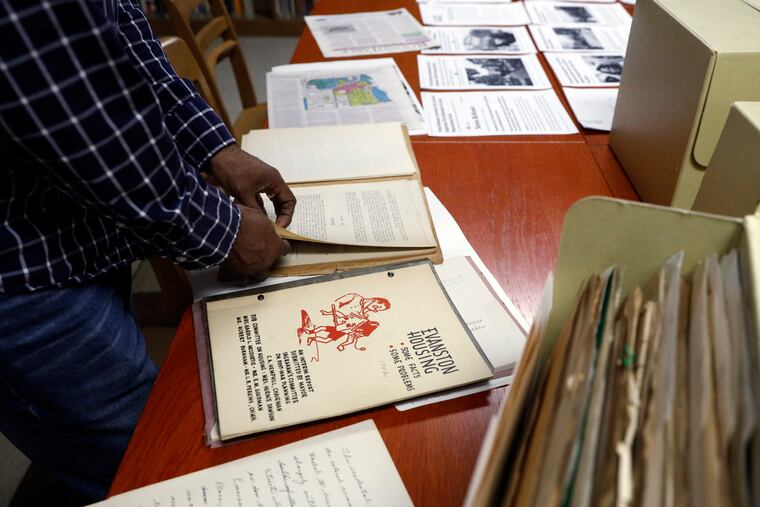

They may be encouraged by Evanston, Ill., vaunted this spring for being the first American city to pay “reparations.” But more accurately, Evanston created a housing voucher plan creating $400,000 in homeownership and improvement grants, plus mortgage assistance — which cannot come close to meeting the sums needed to close the wealth gap for its Black residents. In a city with about 11,000 eligible Black recipients, the total needed to erase the gap would be $3.3 billion. The annual city budget is $300 million. And this captures the fatal flaw of these local and state proposals that, in the absence of a precise definition, parade merrily under the label of “reparations” while offering no such thing.

In our work, we have been specific about the appropriate contours of a plan for Black reparations, emphasizing that such a plan must prioritize elimination of the wealth gap between Black Americans who are descendants of persons enslaved in the United States and white Americans. The gulf in wealth between Black and white America is the best single economic indicator of the cumulative, intergenerational effects of racial injustice. We estimate that this would require an aggregate expenditure of at least $11 trillion or an allocation of upwards of $360,000 to each of 40 million eligible recipients.

State and local governments simply can’t produce that kind of money.

Assume, conservatively, that the average payout per individual needed to bridge the racial wealth disparity is $300,000. Nationally, about 90% of Black Americans are persons with ancestors who were enslaved here.

Amherst, Mass., where advocates have cited Evanston’s program, announced in late June that it has created a fund to pay reparations to Black residents. It has an eligible Black population of around 2,000 people. To erase the racial wealth gap, it would need $600 million. The entire town budget is $85 million. Asheville, N.C., which claimed to adopt a reparations plan a year before Evanston and allocated $2.1 million for the program this June, has an eligible Black population of about 9,000. Juxtapose the $2.7 billion needed to close the gap for its residents against the $200 million city budget.

» READ MORE: Penn Museum owes reparations for previously holding remains of a MOVE bombing victim | Opinion

And in Philadelphia, the estimated eligible population is about 650,000 Black residents. To eliminate the racial wealth gap for them would require a $195 billion expenditure in a city looking at a $5.3 billion annual budget.

What about state government capabilities? California has an eligible Black population of about two million. The $600 billion needed to close the racial wealth gap is more than twice the state’s current $260 billion budget. New York, also establishing a state-level reparations commission, has an estimated 2.3 million eligible Black recipients. They would need to receive $690 billion to eliminate the racial wealth gap, and the state’s budget is $212 billion.

In Pennsylvania, an estimated 1.3 million eligible Black recipients would need to receive $390 billion to eliminate the gap, but the state’s budget is closer to $40 billion.

Suffice it to say neither states nor localities taken individually or collectively have the ability to close the Black-white wealth gap, which must be the central objective of true reparations. Labeling these local attempts “reparations” may simply reflect an attempt to score political points, and distract from substantial efforts.

In contrast, the federal government is the financially capable party. As the response to the pandemic has demonstrated, the federal government has the ability to mobilize, quickly, vast resources — spending $5 trillion on pandemic-era stimulus.

The federal government also is the culpable party.

Crucially, the federal government also is the culpable party. Black Americans are about 12% of the nation’s population yet possess only 2% of the nation’s wealth. The federal government has produced and maintained the conditions that produced the Black-white wealth gap, including slavery, legal segregation, white terrorist massacres and lynchings leading to seizure of Black-owned property, redlining, discriminatory application of the GI Bill, mass incarceration, and employment bias.

For 100 years, starting in 1862, the federal government invested in white wealth accumulation with the Homestead Act. Some 1.5 million households received tax-free 160-acre land grants out west, completing the colonial settler project, which translates into 45 million white beneficiaries today. When the Civil War ended, Black Americans were promised — and then denied — 40-acre land grants along the Southern coast, land confiscated from the Confederates. Their descendants are the people who are eligible to make a reparations claim.

Reparations for Black American descendants of slavery in the United States must be a federal project. States and localities should not continue to describe any actions they take as “reparations.” Let’s reserve that term for a comprehensive national program that brings average Black wealth into alignment with average white wealth.

William Darity Jr. is the Samuel DuBois Cook Professor of Public Policy and African and African American Studies at Duke University. A. Kirsten Mullen is a folklorist and the founding director of Artefactual, an arts consulting organization based in North Carolina.

The Philadelphia Inquirer is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. See all of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.