Searching for Irish American identity in West Philly’s lost Corktown | Perspective

In the dozen blocks between the taco shop and the church, we can start to trace the path of Irish Philly in 2019.

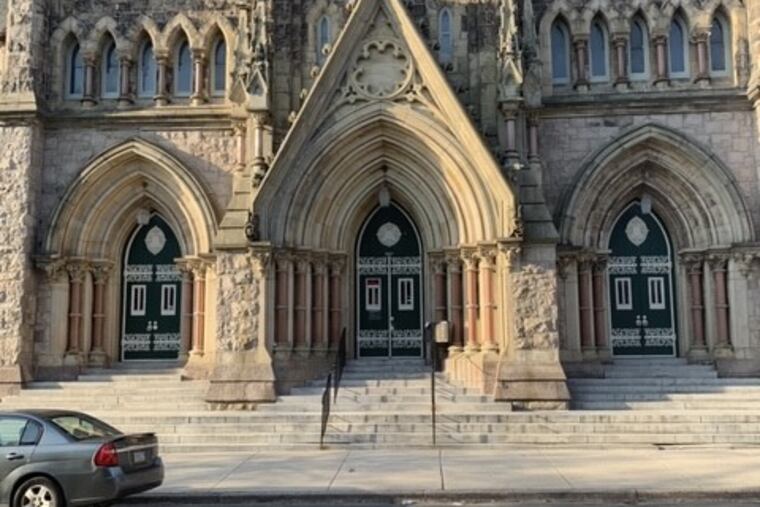

In the Mantua section of West Philadelphia is St. Agatha’s, a massive, shuttered Catholic church. The church is adorned with dark green paint, a “no trespassing” sign, and a package delivery notice for a priest. It sits in a neighborhood once known as Corktown, a forgotten hub of Irish American life.

I walked to St. Agatha’s last weekend from Wahoo’s Tacos & More, a stop on the annual St. Patrick’s Day bar crawl known as the Erin Express. Wahoo’s serves Mexican food with Asian and Brazilian influences. Revelers sat at tables outside the University City restaurant eating tacos and drinking Bud Light on a patio full of fluorescent St. Paddy’s gear and Eagles jerseys.

I first learned of Corktown four years ago from my grandfather, a second-generation immigrant from County Tipperary. But no one at Wahoo’s had heard of Corktown — and neither had any of the multiple Irish historians and enthusiasts I spoke with. So I went to the neighborhood myself, to answer a question that’s burned in my mind ever since I was a kid eating “Irish potatoes” candy spun from shredded coconut: What is Irish American culture made of?

In the dozen blocks between the taco shop and the church, we can start to trace the path of Irish Philly in 2019.

Irish people didn’t come to the United States as a nation but as individual counties. Irish American identity emerged as desperate immigrants banded together under spine-splitting work on docks, canals, and railroads.

The Irish lived in Mantua at least since the 1870s, when St. Agatha’s was built. While the name Corktown merits a tiny, undated mention in the city’s place-names records, the 50-odd blocks tucked beside the Schuylkill have long been on the books as Mantua. Even in its heyday, the name Corktown was known mostly among Irish residents, who lived there with Italians, Jews, Germans, and African Americans. As more black people moved into the area, many fleeing the Jim Crow South, discrimination against the newcomers fueled racial violence, which contributed to a white exodus from West Philadelphia. By the 1960s, most Irish Americans had left the neighborhood for the suburbs.

Tracking down people who grew up in a place called Corktown has become an increasingly bittersweet exercise, as the last generation enters its 80s and 90s. Everyone who’s ever told me about the neighborhood is dead now, including my grandfather. Three years ago, I went to visit Richard O’Mara, who wrote a memoir of his Corktown childhood, The Street Where They Lived. His dementia had progressed so that we couldn’t speak, and he passed away a few months later.

Today the Irish Philly community endures in both the city and the suburbs, with more than a dozen Ancient Order of Hibernians chapters in the surrounding counties, local St Patrick’s Day parades, and Irish dance classes.

Yet some cornerstones of Irish American community are fading. Mayor Jim Kenney — Philly’s first Irish American mayor since William Green in the 1980s — may be running for reelection, but Irish Americans, who once headed police and fire departments up and down the East Coast and influenced the fate of the Irish Republic with donations to anti-British resistance movements, are no longer the solid voting bloc that championed JFK. Decades of church and school closures in the Philadelphia area, due in part to declining attendance, have meant losing formerly central spaces of Irish American life.

But Mark Bulik, author of The Sons of Molly Maguire, notes that the radical labor traditions of the coal-country Irish who poured into Philadelphia in the 1940s and ’50s are alive in Irish Philadelphia today. Breandán Mac Suibhne, a historian of modern Ireland and author of The End of Outrage, agrees that Irish American culture endures as a spirit of resistance.

“What abides, among people of Irish descent in the States, is a concern for the underdog,” he said. “It exists beyond labor activism and organized politics — there is an understanding, shared by many people of Irish descent, that the Irish were discriminated against.”

And without Irish American activism during the conflict in Northern Ireland known as The Troubles, there may not have been peace. "They protested at British consulates and they lobbied their congressmen. And that engagement, by Irish America, contributed in no small part to the achievement of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998,” Mac Suibhne said. Every generation reaches back, it seems, to grasp the whisper-thin fishing lines that tie us to the island.

Irish Philly was never defined merely by our churches or proximity to Ireland, or our food (corned beef is barely more Irish American than tacos, by the way — we got it from our Jewish neighbors). We are bonded by values forged in crammed boardinghouses on the edges of cities and coalfields.

In this city of neighborhoods, many are hoods-within-a-hood, like Corktown, and that includes today’s University City — the fastest route from Wahoo’s to St. Agatha’s is Lancaster Walk, a pathway through Drexel’s campus that cuts its own lines of sight between school buildings for students, distinct from the city street grid.

The descendants of Irish immigrants to Philadelphia are celebrating with bar crawls and parades this weekend, from Springfield to Lansdale. The search for Corktown has taught me that at its core, heritage is not a food or a place, but an imagined community we build together. Corktown has always been a hometown of the heart and mind, where its spirit remains for the Philly Irish, at least a little longer.

Jess Rohan is an intern on the Power and Policy desk of the Inquirer.