Remembering Tony Auth

A decade after the Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist departed The Inquirer, a colleague reflects on his memorable career — and mourns the decimated state of their still-vital profession.

When the 29-year-old Tony Auth arrived at The Inquirer from Los Angeles in 1971, readers didn’t know what was about to hit them.

The early ‘70s were an era when the Vietnam War was raging, Richard Nixon was raging, and Frank Rizzo was raging. Women and civil rights activists were stepping up their fight for equal treatment under the law. And the nation — newly skeptical in many ways amid the tumult of Watergate — began to demand a greater degree of accountability from elected officials and those in power. Tony drew about it all — and so much more.

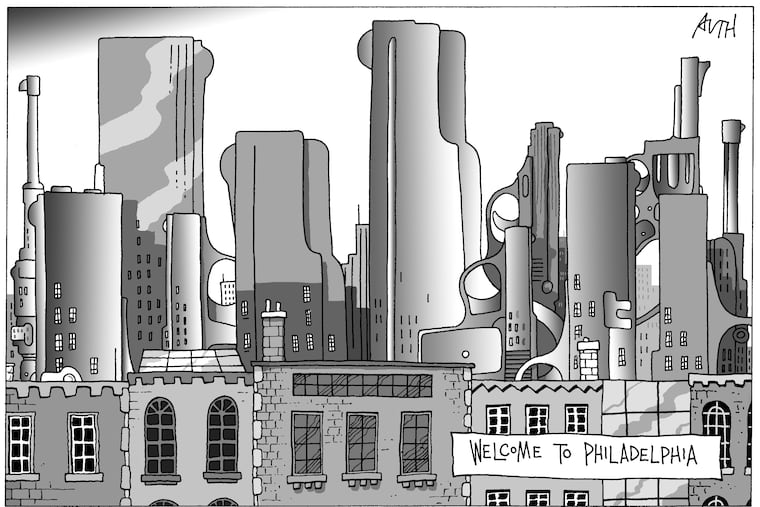

Tony looked past personalities and repeatedly highlighted issues — the blight of poverty, the perils of racism and bias, public corruption and gun violence in cartoons that still grab us by our consciences. So many of Tony’s illustrations resonate as strongly today as the day he drew them.

While Tony’s images were sharp and opinionated, he was affable in person and would sometimes engage readers who called him to complain about his work.

David Leopold, the curator responsible for staging a marvelous retrospective of Tony’s work at the Michener Museum in 2012, said of Tony’s cartoons: “Readers might not read every editorial, but they always looked at Tony’s drawing. Like many of the great cartoonists, while his work seemed topical, he was most interested in human nature. Tony might not show us or our leaders at our best, but he always hoped that things would get better.”

Tony’s clean style with a minimum of cross-hatching or shading attracted many younger cartoonists, including me, whom he kindly welcomed and mentored.

None were more extravagantly helped than the Lexington Herald Leader’s longtime cartoonist, Joel Pett. In 1979, as a young sprout hoping to meet his idols, Joel hitchhiked from Indiana to New York City to attend the opening of an exhibit of the late David Levine’s exquisite caricatures. There he met prominent cartoonists of the day, including Tony, who — when he found out Joel was penniless — invited him to a cartoonists’ post-show dinner, gave him train fare to Washington, and brokered an introduction to the Washington Post’s iconic, now departed, editorial cartoonist Herbert Block, who famously signed his work “Herblock.”

Joel is still grateful — and he’s hardly alone in having been a beneficiary of Tony’s grace and generosity. Before he became a CNN news anchor, for example, aspiring cartoonist Jake Tapper took his work to Tony, who suggested books to read and other cartoonists’ work to follow. Tapper said: “Tony would take me out to lunch, he would call me on the phone. ... He was a friend and mentor and mensch.”

Tony died of cancer in 2014 at age 72, leaving behind his wife, Eliza Auth, and two beloved daughters. Eliza recounted how Tony would get up in the morning, read the newspapers, and start sketching ideas before heading into his office on the sixth floor of the former Inquirer building at 400 N. Broad St., which now serves as the headquarters for the Philadelphia Police Department. (When asked who now occupies Tony’s office, a police public affairs officer helpfully revealed — wait for it — “police.”)

Eliza said: “Tony loved his work. He came home at the end of the day and began to draw.”

This year marks a decade since Tony left The Inquirer through a buyout after 41 years in the newsroom. His departure was yet another in a wave of retirements, voluntary separations, and dismissals over the last quarter century that have decimated the ranks of newspaper cartoonists. In the 1980s there were somewhere around 150 cartooning jobs in U.S. newsrooms. Today there are about 30 and not all of them are full time. Similarly, comic strips have withered as the newspapers that spawned these distinctive visual art forms have largely shrunk to shells of their former selves — their demise accelerated by the onslaught of online media where no one has to pay for news they don’t agree with.

As a result, once-robust papers like The Inquirer no longer have their own in-house editorial cartoonist, so they are rarely able to feature on their pages homegrown visual commentary on City Hall or the state legislature — the exact people who most need a pen pointed in their directions.

Instead of finding homes on newspaper editorial or comics pages, today’s cartoonists are intrepidly creating their own digital outlets. You can find your preferred comic humor online without having to look at work you disagree with. It’s great! With the work correctly curated, you never have to have your viewpoints challenged in the virtual world.

Traditional editorial cartooning may be fading, but Tony Auth — mentor and mensch — was recognized as one of its masters for four decades.

Tony wore his many awards, including the Pulitzer Prize, lightly. In 2005, he received cartooning’s highest honor, the prestigious Herblock Prize, named for the Post icon whom Tony helped Joel Pett meet all those years ago. Accepting the award, Tony said: “Our job is not to amuse our readers. Our mission is to stir them, inform and inflame them. Our task is to continually hold up our government and our leaders to clear-eyed analysis, unaffected by professional spin-meisters and agenda-pushers.”

And so he did.

A winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Signe Wilkinson spent 35 years as an editorial cartoonist at The Inquirer and the Daily News.