University of the Arts in the 1980s was full of wit and brilliance and weirdness

What does it feel like when your college disappears, just like that? I’ll tell you.

I was out for a walk alone Friday evening when my college disappeared.

A friend texted me a link to an article. I wasn’t wearing my glasses. I had to squint. At first, I could only make out the photo, but I recognized the building depicted immediately, an impressive pediment lifted heavenward by four massive columns. Hamilton Hall, on Broad and Pine Streets in Philadelphia, the main building of the University of the Arts, where I spent four years as an art student in the late ‘80s. I narrowed my eyes further to read the headline. That’s when my college vanished, poof.

“The University of the Arts is closing June 7, its president says.” I stopped in my tracks.

I texted the news item to three other friends, fellow UArts alums. And then I stood there in the middle of the path I was walking in a park in St. Louis and read every word. People walking around gave me a wide berth, possibly imagining from my demeanor that I was receiving devastating news. And I was.

What does it feel like when your college disappears, just like that?

I’ll tell you.

The first thing you might think — a little frantically, a little selfishly — is whether your degree is worth anything. After all, if the place that granted you the legitimacy of a degree suddenly becomes utterly illegitimate itself by ceasing to be, where does that leave you?

That feeling will pass. You’ll reassure yourself that your degree still counts. Surely you’re grandfathered in. Your current employer won’t hold it against you. You haven’t, after all, deceived anyone.

But you might feel deceived.

Shouldn’t a university’s foundations be solid, its roots deep, its stewards responsible enough to ensure not only quality education but continuity? UArts has been around for nearly 150 years. Just how did those in charge manage to screw things up so badly? Hamilton Hall has columns, for goodness sake.

At this point, perhaps you’ll take a moment away from yourself to imagine the current students. Maybe, like me, you’ll chide yourself for taking as long as you did to get around to them. Those poor kids. Just off for summer break, or perhaps getting ready for summer session classes, and then, boom, it’s all gone.

In an email sent Friday by the university’s president and chair of the board of trustees, they promised to “support our continuing students in their progress to degree by developing seamless transfer pathways to our partners: Temple University, Drexel University, and Moore College of Art and Design, among others.” But most of these kids won’t want “seamless transfer pathways.” What they’ll want is to return to the university that accepted them, the university where they did their foundation year (the first year, in art school). To return to where their professors and friends are. To come home, because that’s what college is — the first home away from home for so many. Now lost to these kids.

Lost, too, to those of us whose home it was all those years ago.

And that is when the devastation will really set in.

That is when the devastation will really set in.

When UArts was my home, I used to watch the sun set over West Philly from a window on the eighth floor of Anderson Hall with my friend Tucker. Across the street was a billboard with Tony Danza’s giant face advertising reruns of his sitcom. We’d ask each other, “Who’s the boss?” over and over. We still make that damn joke.

How I loved the eighth floor. The painting department! That smell of turpentine and linseed when I got off the elevator, the riot of unfinished canvases at every turn, some of them brilliant works in progress, some not so much. I remember a wooden easel leaned up against a trash can, one of its legs cracked. Someone had stuck a note to it: “Baroque Easel.”

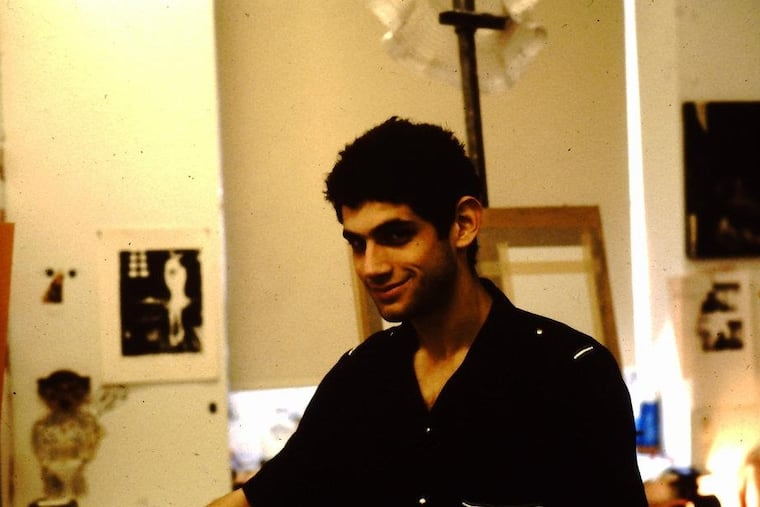

I felt surrounded by wit and brilliance and weirdness (this was art school in the ‘80s, after all), and this emboldened me and pushed me to take risks. I found some of the best friends I have in this world at UArts. I met Tucker. Joe. Dari. Melissa, who would later introduce me to the woman I’d marry and have a child with. It’s a place of so many beginnings for me.

My daughter is a talented artist, a junior in high school. I’d recently entertained the idea of her attending my alma mater. I thought we’d visit. I could show her the eighth floor of Anderson Hall, maybe some kid would let me see whatever they were working on in the very studio I used to share with Tucker. Then I’d take my daughter down to the street, buy some pretzels, and eat them on the impressive steps in front of Hamilton Hall, just where I’d sat with all my friends in our strange haircuts and paint- and clay-spattered clothes all those years ago.

I don’t know whose fault this is. I just know my alma mater is gone. My daughter can’t attend. If I ever do bring her to see Hamilton Hall, what will it be? What do they turn giant Greek Revival buildings into? Banks? Targets? Or do they just hang around as ruins, reminders of something great that was once there?

David Schuman is a writer and teacher living in St. Louis, where he directs the creative writing MFA program at Washington University in St. Louis. He is an alumnus of the University of the Arts (BFA, painting, 1990).