Nondisabled people ran with work-from-home accessibility. Now do the same for voting. | Opinion

As of 2016, nearly 80% of polling places nationwide were inaccessible to disabled voters.

With the global pandemic threatening the lives of citizens across the country, people are being forced to think in a way they haven’t before: like disabled people. Why should elections be different?

For decades, voting in person has been an act of resistance, a way for marginalized people to show up after eras of voter disenfranchisement to make their presence known and counted. Now, with a global pandemic, those in authority must consider accessibility for not just the disability community, but the health of all their constituents.

Disability rights advocates have long maintained that accessibility everywhere can be good for everyone. As a disabled person who has been routinely denied access or told it’s too cumbersome, it can be somewhat frustrating to watch nondisabled people embrace it now that it is necessary for their own health. Still, voting is one area I’ll be happy to have embraced by nondisabled people — and I won’t even be snarky about it, as long as it means equitable access for all.

Voting for people with disabilities has long been fraught with access issues and dismissive attitudes that keep us from voting. Everything from the lack of accessible candidate websites to machines that aren’t plugged in can impact whether a disabled person votes. As of 2016, nearly 80% of polling places nationwide were inaccessible to disabled voters. If disabled people voted at the same rate as those without disabilities, an estimated 2.3 million more people would cast their ballot.

Disabled people have the potential to change the course of history. Voting inaccessibility should not be a barrier we have to face on the road to doing so.

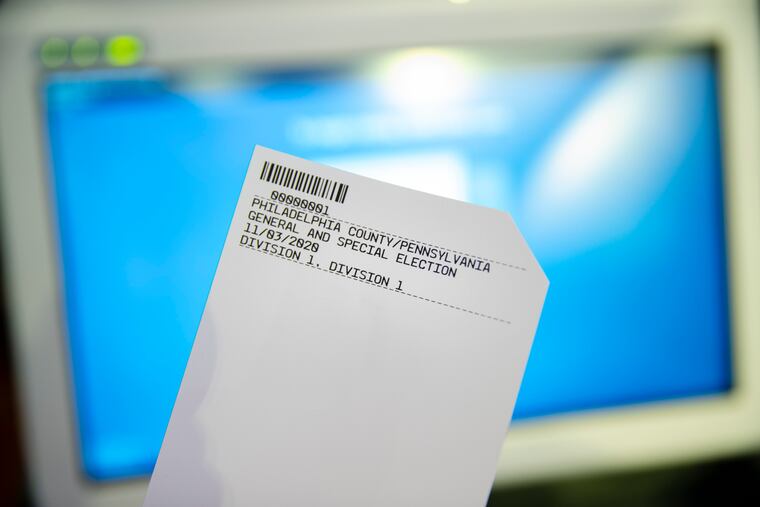

Mail-in ballots are a step in the right direction, but too often, proximity is confused with accessibility. This leaves nondisabled people to believe that having a ballot in hand is where the fight for access ends. But things like complex ballot language leave those with intellectual disabilities behind, while signature-matching can make it difficult for those with tremors or sensory or mobility issues to sign in agreement with previous signatures. That makes it difficult to complete a mail-in ballot privately and independently.

Recently, I was asked to host the online Vote for Access series about this subject. I spoke with disabled voters and disability advocates across the country about their experiences both voting and advocating for the right to vote. It was both heartbreaking and empowering.

As a black disabled woman, I know what marginalization can feel like, but I don’t pretend as though all experiences are universal. I was unprepared for how fervent and steadfast disabled voters could be. One man from Detroit, Eric Patrick Thomas, fought for his right to vote for 20 years, routinely filming his experiences with inaccessibility. In one viral video, he showed viewers that the voting machine wasn’t even plugged in.

Another voter, Lawrence Carter, said he often comes across people who don’t think disabled voters know what they’re doing or could possibly understand the subjects they’re voting on. Another participant, Ric Nelson, echoed the sentiment.

Disabled people are quite involved in politics. As we are currently witnessing, our lives depend on it.

» READ MORE: Voting is different in Philly this year. Here’s what you need to know for Tuesday’s coronavirus primary.

Progress has been made, though. #CripTheVote, started before the 2016 election by Alice Wong, Gregg Beratan, and Andrew Pulrang, has helped shift the narrative about disabled voter engagement and the topics important to us. It also emboldened disabled voters to speak to candidates directly about the issues we’re passionate about. Consequentially, the 2020 campaign trail has seen more policy plans for people with disabilities than ever. Candidates have hired members of the disability community to handle outreach. Advocates like Neal Carter of Nu View Consulting, working with Sarah Blahovec, are training disabled candidates to run for office themselves.

To not ensure equal access to voting means disabled people are not given a say in how our lives can be lived and the progress we want to see. We represent 19% of the population. We are a force of nature. Equitable access to ballots can move mountains for disabled people — better yet, it is a way for us to move mountains ourselves.

Imani Barbarin is the director of communications and outreach for Disability Rights Pennsylvania and the host of the series “Vote for Access.”