Why families should think twice about international adoption

International adoptees are not an economic product, not a problem to be solved, not a reflection of one’s Christian goodness nor a solution to one’s desire to build a family.

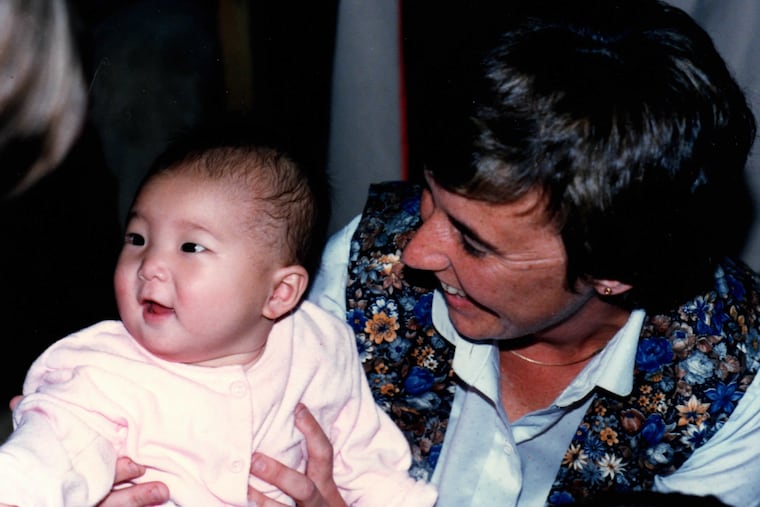

After being adopted by white parents in Las Cruces, New Mexico, when I was almost 6 months old, I recently made my first trip home to Korea at age 38.

Before and during that trip, I waded through all the information I could access about my adoption and found glaring evidence of the transactional nature of my beginnings — ample proof of myself as a product. I recovered receipts for payments my adoptive parents made to various adoption agencies, and saw a delivery slip my adoptive mom signed upon picking me up from the airport intact, not unlike an Amazon package delivered on someone’s front stoop.

That’s how I have felt at times — like an export, a package someone ordered that was shipped overseas. I’ve always had a sense of existential dislocation, as if I belonged somewhere else, or nowhere at all.

Growing up in Las Cruces, I never learned any Korean history, language, or culture. The racial dissonance of being Korean in a white family in a white community proved immense and unrelenting. I did not meet or see another Asian person until I was in the sixth grade.

My personal history is a product of the Korean War, which, decades before my birth, drove the first waves of adoption from the country, stoked demand for Korean babies, and established an infrastructure for international adoption.

In 1955, driven by a missionary fervor to save the world’s orphans, a Baptist couple in Oregon named Bertha and Harry Holt pushed the passage of a bill that authorized them to adopt eight Korean War orphans, where a previous federal law limited families to two.

The following year, the Holts founded Holt International to systematize foreign adoptions. Now, a modern multistory building and an entire subway station in Seoul are dedicated to the Holts’ legacy, and an estimated 200,000 Korean children have been adopted overseas.

The organized, systematic practice of Korean adoption formed a template of sorts that was exported to other countries — including Vietnam, Ethiopia, Guatemala, and Haiti — where rich Westerners rushed in to rescue children after wars or earthquakes. The pull toward international adoption was openly encouraged by evangelical Christian leaders in the early 2000s as a way to live out their faith and purported pro-life principles.

Adopting and relocating children from their home countries removes them entirely from their racial, social, and historical context. My adoptive family placement was arguably less traumatic than many of my compatriots, some of whom suffered abuse at the hands of their adoptive families or were “re-homed” — a tidy euphemism for children who are relinquished by one adoptive family and must be placed with another.

I wonder if prospective adoptive families — and the agencies that support them — might reconsider their motivations for rushing to adopt children after disasters.

What unintended consequences might they be enabling, such as the procurement of children to meet adoption demand through unscrupulous means, including coercion, payments, and even kidnapping?

In Vietnam, for example, orphanages were places where families traditionally left children temporarily for safety reasons, or to help them get through lean times. But children were often placed for international adoption, even when they had known family members who visited them frequently. In Haiti, after the 2010 earthquake, the push to expedite the post-disaster adoption process resulted in chaos and a relaxation of safeguards that are in place for the welfare of adoptees. In 2018, Ethiopian adoptions were halted after an Ethiopian adoptee in Seattle died due to abuse by her adoptive parents. A current pause on international adoptions from Ukraine due to the war with Russia inspired multiple private rescue attempts, one of which led to a child trafficking probe.

It is important to question the instinct that feeds these adoptions. When considering the cost of international adoption (currently between $20,000 and $50,000), and the cost of raising a child to adulthood (placed at more than $300,000 by the Brookings Institution), I have to wonder: What could that amount of resources do to support families in other countries suffering from poverty? Could that money be used instead to place children with other families in their home countries, and rebuild local economies and reunify families after disasters — which would all benefit the same children adoption aims to help?

If prospective adoptive families feel like Bertha Holt did when sending money to Korean orphanages, that these efforts are still not enough, then perhaps the inclination toward international adoption may be more motivated by a sense of saviorism and self-aggrandizement, with just a hint of neocolonialism, rather than by true altruism.

Adoptees are not an economic product, not a problem to be solved, not a reflection of one’s Christian goodness, nor a solution to one’s desire to build a family. We are people. We come from our own racial, ethnic, political, and cultural heritage that is rich with context, history, and nuance. We are endowed with our own independent set of gifts, challenges, and experiences.

We deserve to be surrounded and raised by people who see us that way.

Longtime Philadelphia public schoolteacher Meredith Seung Mee Buse is a writer, educator, and Korean American transracial adoptee who lives in South Philadelphia. @msmbuse