The travesty of America’s failed coronavirus response as seen from the steps of a school | Maria Panaritis

Parents unemployed. Computers on backlog. Kids struggling with virtual learning. And yet, Darby Township School forges on.

I pulled up to Darby Township School for a reality check.

After months of hearing and seeing parents elsewhere shame-scold one another on Facebook over pandemic learning protocols and pressures all day long from their far more white-collar bubbles, I had been longing for a glimpse into true need.

I got a sliver of it Wednesday morning at the grades 1-through-8 school in Delaware County. Darby Township is in a school district, Southeast Delco, where COVID-19 positivity rates the week earlier had been logged at about 30%, according to the assistant principal. It’s in a zip code full of Northeast Philadelphia-style rowhouses. A place where many parents seem to work service-sector jobs, are frontline workers, or are poor.

For many of us, tallying the costs of this terrible pandemic year begins and ends by gazing inward. This once-in-a-century crisis has been extraordinary and heartbreaking in ways large and small. But it is time to look beyond our own navels and see the travesty in our nation’s failure to manage the coronavirus impact on schools a full nine months after it exploded in America.

Even the most determined district leaders in under-resourced communities are scrapping like mad to contain damage being done to children and families every single day while learning is happening at home — and where intensifying crises are largely beyond the view of social workers.

“I’m going after school today ... to a mom with three kids ... and dropping off their Christmas presents ... because they don’t have a car,” principal LeAnne Hudson had told me when I first interviewed her, by phone, earlier this month. I had found her after I wrote a column about a new group, Teachers’ Teammates, which helps put donated supplies into the hands of teachers in needy districts.

Southeast Delco is low-income enough that all students get free lunches. But this year, things are even harder. And teachers may only sense this when a student fails to log on for class.

» READ MORE: 3 people, 200 square feet: Managing homelessness, remote school, and life in a pandemic

“My contact with the parents has increased,” social worker Stephanie Freeman said as we met recently on the front steps on food distribution day. “Now a lot of my families are home with their kids, but they’ve lost their jobs because of the pandemic.”

A few weeks back Hudson sent out a text message blast to families: Who needs a winter coat for their kids?

“I gave out about 30 coats,” she said.

Imagine, if you will for a moment, how different life must be for children in private schools or who have comfortably stay-at-home parents in public schools.

Because private schools may limit admissions and charge tuition, they have delivered five-day-a-week, on-campus instruction for all who want it this fall. Even well-heeled public school districts such as Lower Merion, Radnor, and Cherry Hill have managed only a few hours of in-class instruction through hybrid models. Philadelphia, Norristown, and Upper Darby have failed to open at all in person for the general population.

» READ MORE: At the elite Shipley school in Bryn Mawr, money is no object in coronavirus-reopening plans | Maria Panaritis

Darby Township, where class sizes average 25 to 28, is too crowded to safely open five days a week and so has been all virtual.

Despite the school’s proximity to one of the largest telecommunications corporations in the world, the district was stymied for months in putting enough laptops into children’s hands. An order was delayed by supply problems, which left students having to share a single machine with their siblings in some households. The new computers finally arrived just a few days ago.

School workers and parents have been heroic. But such heroism alone is an insufficient solution.

When I met Home and School Association treasurer Francesca Barley at the school the other day, she told me a story. During her fifth-grade daughter’s video-broadcast class, Barley saw the parent of another child connect from her job as a hospital nurse.

“She wanted to know if her child was on the connection,” Barley said.

» READ MORE: Zoom and gloom: Virtual schooling has begun, and it is unsustainable | Maria Panaritis

Apparently, a babysitter was not succeeding in getting the child to log on and pay attention to the learning.

Imagine being that nurse. Imagine being that child.

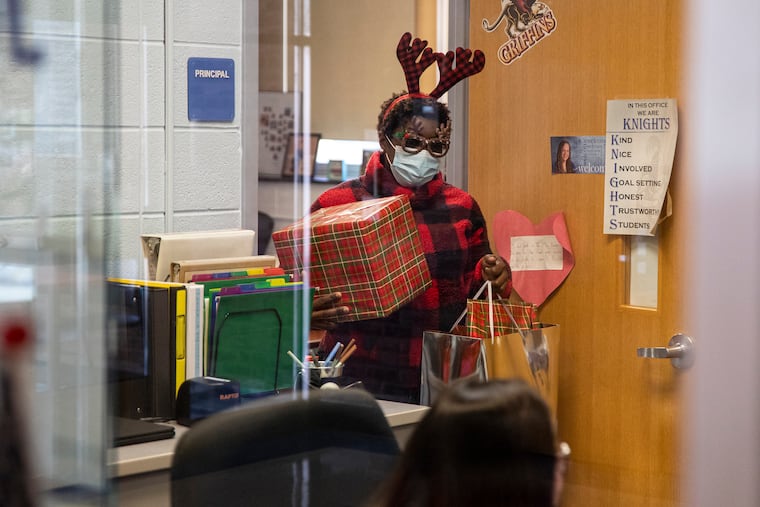

Imagine also being the single mother of two kids to whose home social worker Freeman, in reindeer antlers and psychedelic Christmas glasses when I saw her Wednesday, would soon be delivering wrapped toys and clothes.

Sometimes, Freeman told me, parents will log onto the social skills class she teaches to children each week in the 650-student-large school and ask to talk afterward.

They ask where the nearest food bank is. Tell her they’ve lost their job. They ask for help because the government cut off their food stamps or Medicaid due to offices being closed due to the coronavirus and no one being able to send in renewal documentation.

With donations from a nearby church, police, and school staff, Freeman and Hudson gathered and delivered wrapped toys, coats, shoes, and other gifts for several dozen of their most needy children ahead of Christmas Day.

“Sometimes a parent will say, ‘Please don’t use my name but a friend told me their husband is not working for two weeks because of quarantine for COVID,’ ” Hudson said.

The principal then calls the parent.

This is what hardship looks like. This is what America has allowed itself to become. This is where we should be aiming our rage as presidential Inauguration Day looms in January.

I watched Wednesday as children showed up to claim $5 Wawa gift cards, provided by the local police department, for having made honor roll.

“I’m buying candy,” fifth-grader Sydney Barley said when I asked how she would be spending the dough.

As the principal and social worker carried gifts to a nearby car, I heard a parent whisper as she saw what they were doing.

“Oh, that’s nice,” she said. “That’s very, very nice.”

But it is not enough.