Bad policing costs lives. So why are fired officers allowed to join other departments? | Solomon Jones

Daniel Pantaleo, known for his involvement in the death of Eric Garner, must never again be allowed to work as a police officer.

I remember the scene vividly. Eric Garner, surrounded by police officers on a Staten Island street corner, with then-Officer Daniel Pantaleo’s arms locked firmly around Garner’s neck.

“I can’t breathe,” Garner said 11 times in a videotaped tragedy viewed by millions. At the end of it, Garner lay motionless on the ground, and the breath that he’d longed for — begged for, really — was gone from his lifeless body.

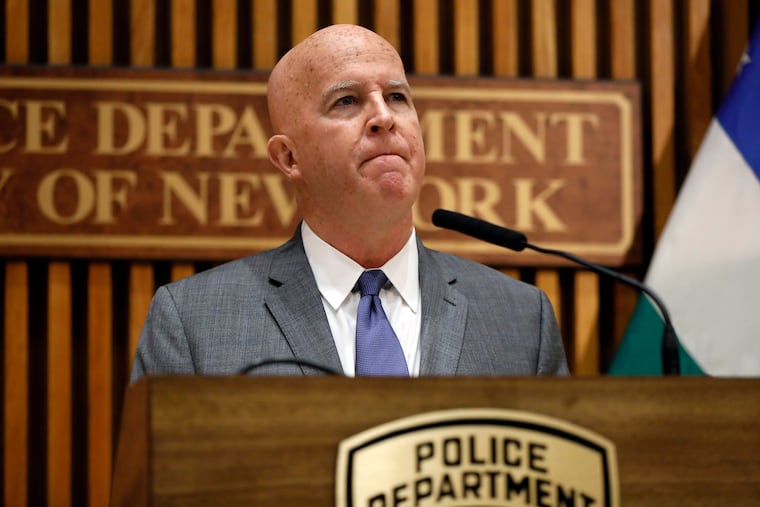

That was five years ago, and after that violent incident, spurred by Garner’s being stopped for selling loose cigarettes, Pantaleo was relegated to desk duty. Garner became an icon of a movement. And though Pantaleo was never criminally charged for his actions, he was fired this week by the New York Police Department after a judge recommended that he be removed from his job. Absent the criminal charges that I believe Pantaleo should face for killing Garner, there is one thing that should happen now.

Pantaleo must never again be allowed to work as a police officer.

That edict should apply to every police officer who has been deemed unsuitable to work as an officer in America. That includes the 13 police officers who were fired from the Philadelphia Police Department after posting violent, racist, or otherwise threatening or abusive material on Facebook.

That’s because such officers pose an imminent threat to the public. In many other jobs, mistakes, incompetence, or abuse could result in a loss of money, but bad police officers cost people their lives. That’s especially true in communities of color, where police abuse is statistically more likely to occur.

Unfortunately, the structure of policing in America is not designed to keep dangerous, racist, or incompetent cops off the street. First, there is no government-run public database of officers who have been disciplined by their departments, though USA Today and the Invisible Institute constructed a private database this year. And even when officers are investigated, the results are often hidden from public view. In Philadelphia, for example, when citizens sue and win after alleging police abuse, the settlement amounts are not always publicly available, a fact Councilwoman Helen Gym is trying to change with new legislation.

There are those who say the system should remain the way it is. I disagree. Our current system allows fired cops to move seamlessly from one department to another. Such cops pose a danger to all of us, and especially to people of color.

Take Darren Wilson, an officer who was among those fired when the town of Jennings, Mo., disbanded its police department in 2011. The town council made the decision after the white officers there were repeatedly accused of abusing black residents.

After he was fired in Jennings, Wilson applied for a job in nearby Ferguson, where he shot and killed unarmed black teen Michael Brown in an infamous 2014 shooting that spurred national protests. In a decision that continues to spark controversy, a grand jury declined to criminally charge Wilson in connection with Brown’s death.

But Wilson isn’t the only one. Timothy Loehmann was a patrolman in training in Independence, Ohio, when a firearms instructor said Loehmann was “distracted” and “weepy” during firearms training, and Deputy Chief Jim Polak of the Independence Police Department recommended firing Loehmann.

In a November 2012 memo about Loehmann, Polak wrote that Loehmann “would not be able to substantially cope, or make good decisions, during or resulting from any other stressful situation.”

Four days after Polak wrote that memo, Loehmann resigned. In 2014, as a rookie patrolman in the Cleveland Police Department, Loehmann encountered a stressful situation. He shot and killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice, a black child who was playing with a toy gun at the time.

Loehmann was fired by the Cleveland Police Department in the wake of that shooting, and unbelievably, he was hired by the Bellaire, Ohio, police department before bad publicity forced him to withdraw.

I’m not sure that Daniel Pantaleo would turn out like Wilson and Loehmann if he were hired by another department. Nor do I know what would happen if the 13 cops fired after the Philadelphia Facebook scandal were allowed to work elsewhere after being dismissed.

However, given the history I’ve seen with fired police officers, I’m not willing to gamble with people’s lives.