Why aren’t slots for opioid treatment filled? City tries to turn the tide. | Editorial

Because of notions that the only real recovery is sobriety, using medication to treat opioid addiction is stigmatized.

The opioid crisis continues to shock with its persistence and casualties. Last year, about 1,100 people died of overdose in the city.

One fact that should bring people to a standstill — if only for a minute — is this: The Department of Public Health recently estimated that between 50,000 and 100,000 people in Philadelphia use heroin. That doesn’t even cover those misusing prescription opioids and other drugs.

While the need for addiction treatment that is based on scientific research has never been higher, slots for such treatment programs remain limited — only 8,822, according to a January report by the Pew Philadelphia Research Initiative. And nearly a quarter of the almost 9,000 slots for this gold standard in treatment are vacant at any moment.

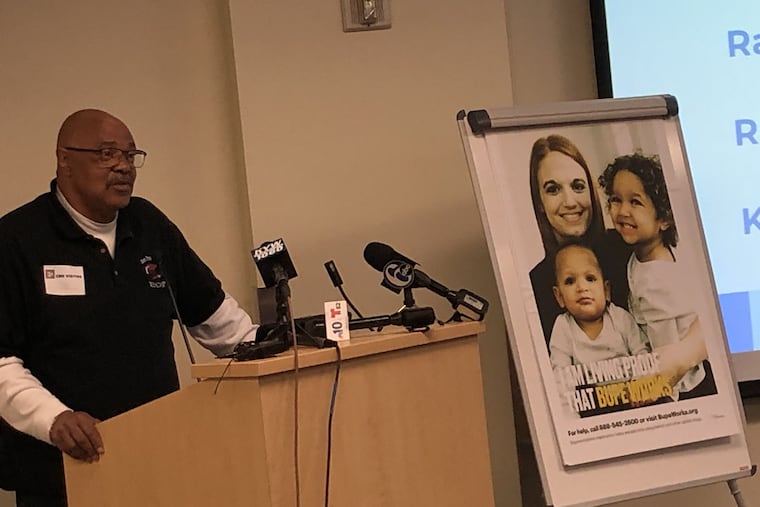

That’s why the Departments of Public Health and Behavioral Health are launching a $200,000 ad campaign in English and Spanish to raise awareness about the availability of medications that treat opioid addiction. The ads feature Philadelphians in recovery who use buprenorphine, or “bupe,” with the slogan, “Bupe works.” (The campaign directs people interested in treatment to call 888-545-2600 or visit www.BupeWorks.org.)

Buprenorphine — sometimes referred to by its brand name, Suboxon — is one of the two medications used to treat opioid addiction that have the largest base of proven medical evidence. The other is methadone. Both are opioids that are longer-lasting than heroin or prescription opioids like Percocet. By taking the place of other opioids, these medications prevent cravings and the fear of painful withdrawal that makes life with addiction so unstable. While some people find recovery in abstinence, studies show that bupe and methadone are treatments that are more likely to last.

But despite their success, they remain controversial — not only among the general public, but also among people in recovery. Because of ill-conceived notions that the only real recovery is sobriety, using medication to treat opioid addiction is stigmatized as nothing more than replacing one substance with another. People who use bupe or methadone are told they aren’t “clean.”

But there is nothing “dirty” about good medicine. There is increasing understanding that addiction is a disease, and should be treated as one — and that just like a person with diabetes needs insulin, some people in opioid addiction need bupe or methadone.

The stigma often stands between people in addiction and lifesaving treatment. And everyone has a role to play in reducing that stigma. It starts with small things like choice of words. Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania found that using words like addict to describe people in addiction is associated with a heightened stigma. Instead, using “people-first” language reduces stigma. (In April, the Inquirer changed its stylebook to discourage the use of addict.)

The new awareness campaign is an important step to spread information that will reach those who need it most. The next logical step is a campaign to educate the public about how the wrong perception of this crisis can be deadly, too.