States must move quickly on virus tracking | Editorial

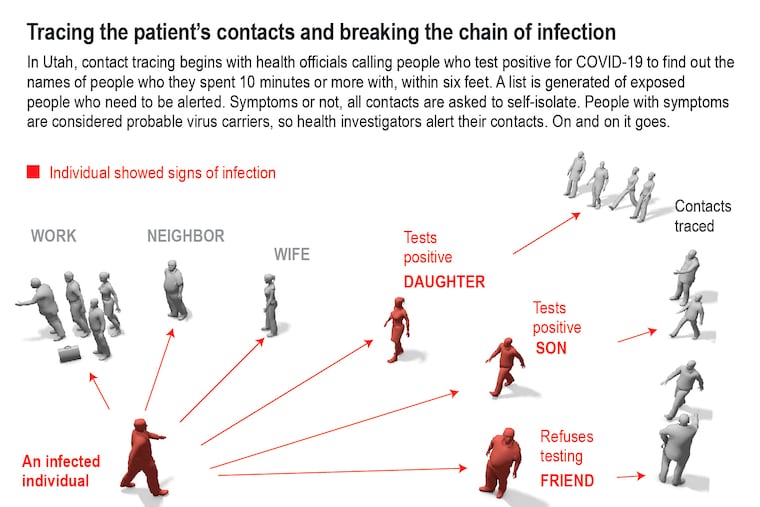

Contact tracing -- in which an infected person provides health workers with the names of others they may have infected -- will help control covid-19. Pennsylvania, New Jersey need to step up their efforts to expand tracing.

As the nation begins to emerge from lockdown, and with no effective treatment — let alone a cure — for covid-19 in sight, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and other states must expand their confidential contact tracing capacity. Officials in Harrisburg, Trenton, and Philadelphia say hundreds if not thousands of additional trained workers may be needed for the painstaking process of identifying and notifying everyone who has been exposed to an infected person and connecting them with services. A landmark Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health proposal estimates that another 100,000 contact tracers are necessary nationwide.

Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Philly have begun preparations, but full deployment of what New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy vowed would be an “army” of contact tracers is still weeks away. Meanwhile, millions of people across the country and thousands in our region are leaving their homes, going back to work, or heading down the Shore. Pressure to fully revive a largely comatose economy is intensifying, incoherent signals from the White House continue, the virus remains contagious, and America once again is playing catch-up with a fast-moving pandemic.

This is inexplicable, because contact tracing’s value as a key contagion control tool — particularly when case numbers are relatively low — is well established. It’s even been recognized by the Centers for Disease Control as a key component of any national strategy. And health departments in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Philadelphia have long operated such programs for sexually transmitted and other diseases, with confidentiality and privacy protections in place.

Since April, the city health department has been collaborating with Penn Public Health to provide coronavirus contact tracing on a small scale. New Jersey’s health department website includes a registration form for people interested in contact tracer training; more than 41,000 people have responded so far. The Pennsylvania health department also is soliciting interest online; state officials say they already have the ability to conduct contact tracing for the counties that are reopening, and are working to increase capacity statewide.

Political and bureaucratic turf battles, as well as technical problems, were largely responsible for delaying the nationwide availability of testing, which, like tracking — and for that matter, social distancing — is a proven infection control tool. But it’s not clear why Pennsylvania and New Jersey aren’t as far along in expanded contact tracing as, say, Massachusetts, where Gov. Charlie Baker announced his state’s COVID-19 Community Tracing Collaborative on April 3. More recently, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Philadelphia have identified federal sources that will help pay for the time-consuming and labor-intensive contact tracing process.

New cases and hospitalizations appear to be reaching a plateau in parts of the region, but hot spots continue to flare up. Chances for exposure will increase as more people venture back into the world, where the virus incubates in infected victims for 14 days and asymptomatic people can unknowingly spread it. Philadelphia and its surrounding counties remain in lockdown, and most New Jersey retail, personal service establishments, and indoor restaurant operations are still closed. The promised armies of contact tracers should be ready for duty by the time the entire Philly region goes back to work -- and preferably before.