Federal money will aid Philly schools, but it’s not a cure-all | Editorial

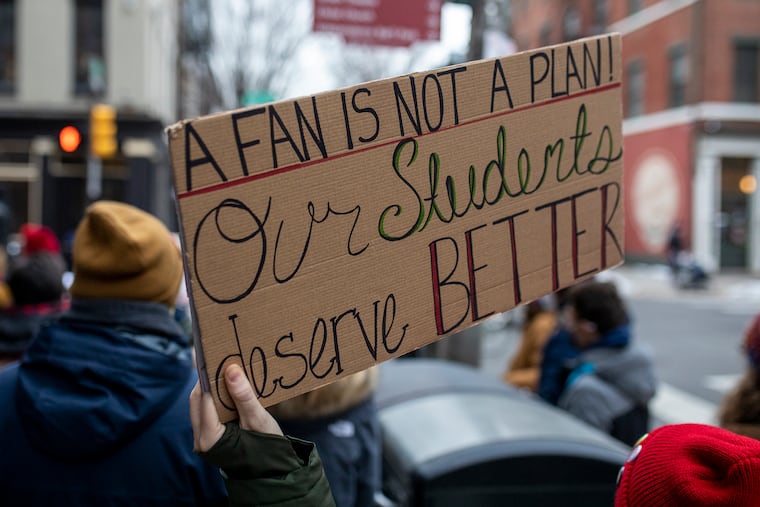

While the federal money can help address the immediate demands, we have to remember that the impact of COVID-19 was made worse because of the underlying deficiencies already built into the system.

The $122 billion in stimulus money that the federal government has allocated to K-12 schools across the country will be an important booster to Philly’s cash-strapped School District. The money is a one-time allocation to help schools mitigate the damage caused by the pandemic. According to the U.S. Department of Education, the money can help schools improve facilities, as well as help address the disruptions to teaching and learning — especially for students hardest hit by the pandemic — and get students back in the classroom.

The School District of Philadelphia is set to get $1.2 billion of that money. Last week, district officials outlined how they expect to spend the money over the next three years.

So far, the plan hits the right notes in acknowledging the priorities the district needs to attend to, though as usual, the devil will be in the details. It has identified four focus areas: Helping to recoup learning loss sustained over the last year of a disrupted school schedule. That means $350 million for enhanced summer school, after-school programs, and other programs, like tutoring. Another $350 million is earmarked to improve facilities. And $150 million will be invested in social services to support the social and emotional needs of students, including increasing counseling. The final focus would reinforce aid for both learners and educators, such as additional supports for English-language learning students, more technology investments, and rewritten curricula.

The impact of this crisis has been devastating — and we won’t even know the full extent of that devastation for years. The profound learning losses are bad enough, but social and emotional losses that have kept kids out of schools and disconnected are even harder to measure. The pandemic has hit low-income families and Black and brown families particularly hard.

While the federal money can help address the immediate demands, we have to remember that the impact of COVID-19 was made worse because of the underlying deficiencies and inequities already built into the system — to say nothing of the additional traumas of rising gun violence and economic disruption have imposed. One-time fixes are important to try to get back on track, but we have to find a way to extend some of these interventions beyond the post-pandemic era (whenever that occurs). That means the state and the city will have to recognize new priorities, and work more effectively together moving forward. That will be a particular challenge in Philadelphia.

The pandemic is an opportunity to keep shining a light on deficiencies, and on flaws that must be fixed. Too many issues — like environmental and health inequities — have been left to wallow.

One of those is charter school funding – especially cyber charters, who stand to get a large outlay of cash as part of the CARES Act. In fact, nearly $1 billion alone will be allocated to the state’s brick-and-mortar charter schools and an additional $212 million to cyber charters, according to a review of Pennsylvania Department of Education data by Public Citizens for Children and Youth.

That last is particularly troubling, since cyber charters benefit financially from a flat-funding formula and little accountability. In his most recent budget proposal, Gov. Tom Wolf proposed reforming the funding of cyber charters, which get the same per-pupil allocation as brick-and-mortar charters. Meanwhile, because of the way the federal CARES Act is distributing money, these schools will be getting payments directly. That’s especially troubling, since cyber charters have not faced the facilities or technology challenges that have devastated traditional schools.

When the pandemic shut down schools, many families signed up for cyber charter schools, despite troubling performance records and big questions about financial accountability. A new infusion of money should compel the state to step up its oversight and work toward stabilizing the charter sector. Those funds are not an excuse for the state to shortchange schools faced with rising costs related to pensions and charter payments, either.

The federal money is a chance to transform the educational system for the future. The School District must also step up its efforts to make sure that the public — especially parents and teachers — has a say in that transformation.