As Norristown grapples with homelessness, forced busing is hardly the answer | Editorial

There are more humane answers than compelling those experiencing homelessness to move. What could help? Investing in smart, equitable growth and allowing for more affordable housing across the county.

When Montgomery County officials conducted a census of residents who were experiencing homelessness in January 2022, it confirmed what many already feared — the problem is getting worse.

Workers with the county’s Office of Housing and Community Development found 568 homeless residents, more than twice as many as in a similar survey conducted in 2019.

Norristown, the county seat, a working-class city and the headquarters of many of the social services and resources that vulnerable populations need, has roughly 20 homeless encampments — a number that has increased because of Hurricane Ida in 2021, which destroyed dozens of affordable rental homes in the county, and the economic woes precipitated by pandemic before it.

In response, Norristown’s council president, Thomas Lepera, planned a stunt. Although Lepera is a Democrat (and the political director for Local 98 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers), he wanted to borrow a page from Republican Govs. Greg Abbott of Texas and Ron DeSantis of Florida.

Abbott and DeSantis sent migrants from their states to Northern cities. Lepera said that he wanted to send busloads of homeless people to the campus of Villanova University, in part to spite an activist professor there that he had clashed with. (At a council meeting Tuesday, Lepera said that his proposal was misunderstood. “I’m not trying to start a war with poor people,” he said. “I’m not anti-homeless.”)

This move comes after Norristown, led by Lepera, closed the county’s only dedicated shelter for single homeless adults. At the time, service providers expressed concern over the county’s capacity to house residents, considering the tight real estate market and lack of available affordable housing.

Lepera is frustrated that people from more affluent areas are telling Norristown how to deal with a situation that doesn’t exist within their own communities. When Lepera spearheaded the closing of the homeless shelter, he complained that “there’re 53 municipalities, townships, and boroughs in Montgomery County. Why does it have to be in Norristown?”

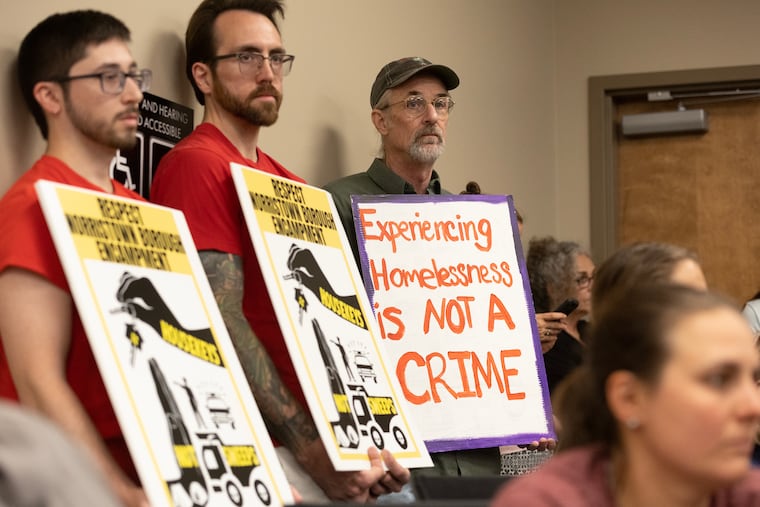

Norristown is also not the only Montgomery County community that’s essentially seeking to criminalize homelessness and poverty. Pottstown, another working-class community, has penalized churches for feeding needy residents and tried to use rental inspections to skirt the Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches and seizures and Pennsylvania’s own constitutional protections.

Whatever the frustrations of leaders like Lepera and those Montgomery County communities may be, the forced busing of homeless people is not a fair, humane, or equitable response. Nor is it a solution.

Organizations that support homeless populations refer to this practice as “Greyhound therapy.” Communities hope that by cutting off all forms of support and providing a one-way ticket out of town, they can fix homelessness.

Sending people further away from friends, family, and trusted connections can make their situation worse and constrain their ability to regain a stable income and home. It compounds homelessness over time.

What would help is investing in smart, equitable growth and allowing for more affordable housing across the county. Research has shown increasingly that homelessness is a housing problem, and many towns are not doing their share to provide shelter.

Like many communities across the country, most municipalities in Montgomery County maintain exclusionary, or so-called “snob zoning,” which ensures high housing costs that effectively price out lower-income residents. These communities also strictly separate residential and commercial uses, at least outside of their iconic Main Streets, meaning residents need access to a car for more basic necessities, another step that tends to exclude those with lower incomes.

While the county is encouraging towns to embrace development oriented around public transit, it has proven to be a hard sell. Ardmore recently rejected an attempt to raise height limits on new buildings, while Upper Gwynedd residents have repeatedly objected to a proposed apartment complex with subsidized units.

Land-use reform has become a necessity in high-cost areas across the country. States as disparate as Montana and Massachusetts have pushed to lower costs. Massachusetts’ MBTA Communities Action Plan could represent a key blueprint for Southeastern Pennsylvania. The Massachusetts proposal ensures that every town does its fair share, rather than pushing demand to just one or two communities.

By raising their drawbridges in the face of minor change, Montgomery County municipalities make urban life less manageable for places like Norristown and Philadelphia. Like “Greyhound therapy,” restrictive zoning prioritizes the desires of individual towns over the needs of the region as a whole, making the underlying problem worse.

With so many towns blocking downtown development, apartments that do get built in Montgomery County tend to be alongside highways near the King of Prussia Mall. Living in that new construction can also be quite pricey. A studio at The George apartment complex in King of Prussia costs nearly $2,000 a month, while a two-bedroom costs over $3,000. That’s more expensive than iconic Center City locations like The Drake.

There is some hope for change. Housing and homelessness were major issues in the Montgomery County Board of Commissioners primary last month. While the commissioners lack direct authority to tackle housing issues — with zoning and land-use decisions often left to townships and boroughs — they can weigh in indirectly, using grant funding and other resources as a carrot to motivate reluctant residents.

Unless they succeed, the inhumane stunts are likely to continue.