Asbestos in Philly schools demands action from district — plus the city and state | Editorial

The District and school leadership need to step up their game, and goes double for the leaders in the city and state, including Governor Wolf, Mayor Kenney and the General Assembly.

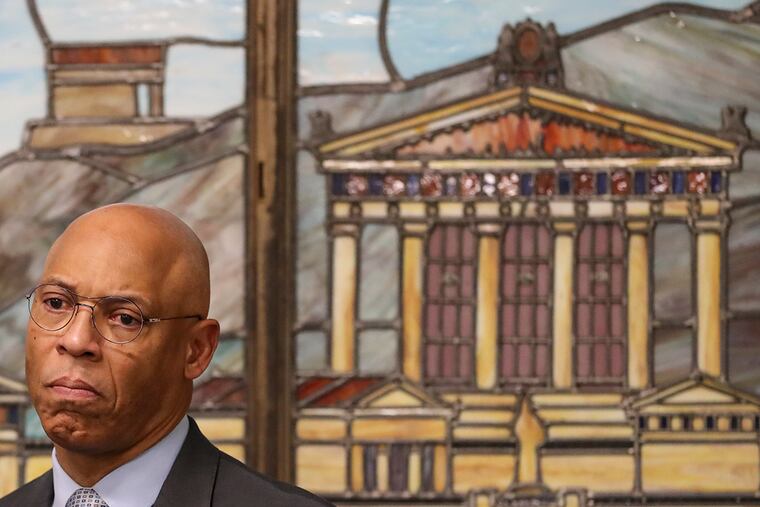

In an attempt to be reassuring, School Superintendent William Hite has said more than once that asbestos, found in the majority of city schools, isn’t dangerous unless it’s damaged.

He would do well to remember that his relationships with parents hold the same fate: dangerous when damaged. Parents are right to be concerned about the toxic dangers in the city’s aging school buildings and the school district’s response, which has often been too slow and not straightforward in communicating to parents a realistic picture of how the district is fixing the dangers of asbestos in schools.

In the last few months, dangerous and damaged asbestos has been found in a building housing Benjamin Franklin High School and Science Leadership Academy, at Meredith Elementary, and last week, at Thomas M. Peirce Elementary. While exploring options for moving Peirce students, asbestos was found at Pratt School currently occupied by preschoolers.

With the average age of Philadelphia school buildings 70 years old, and decades of deferred investment, the toxic schools problem, brought to light in a 2018 Inquirer series, is a huge and complicated problem. The series first highlighted lead paint hazards, which resulted in legislation mandating regular inspections. The focus is now on asbestos, which has appeared to reach a tipping point.

Parents and teachers’ union members say the district has been slow to react and not always forthcoming with information about hazards. Vowing to do better, Hite announced Tuesday a new Environmental Safety Improvement Plan that, among other actions, will expand resources to manage asbestos, strengthen reporting of hazards found in inspections, and do better communicating with parents and other stakeholders when problems are found and fixed.

Hite said that $12 million of a $500 million bond will be devoted to cleaning up asbestos, but also admitted that the full cost for doing it completely could be closer to $150 million over five years. The district doesn’t have the ability to raise that money on its own.

While the district and school leadership need to step up their game, that goes double for the leaders in the city and state, including Governor Wolf, Mayor Kenney, and the Pennsylvania General Assembly.

In a meeting with the Inquirer editorial board, State Sen. Vincent Hughes identified a number of possible revenue sources for fixing schools. But they all require action from a highly polarized lawmaking body. Philadelphia is not the only aging city in the state that hasn’t invested in school buildings; environmental dangers throughout the commonwealth should make this a nonpartisan priority.

Children’s health is a priority, and especially critical in places like Philadelphia, whose high poverty rate makes this an environmental inequity issue. That’s another way of saying: It’s acceptable to poison low-income children and put them at higher risk.

No one would say that explicitly, of course. But generations of neglect say it in another way. That’s why parents should hold the district’s feet to the fire — and include state and city leaders in the call for recognizing the gravity of this problem and finding the money to fix it, without further delay.