The real dirt on ‘American Dirt’: People who claim they want to give ‘voice to the voiceless’ really don’t | Helen Ubiñas

The backlash is a long-overdue reckoning for access and opportunity and respect.

Oh, I’ve seen this show before. Starred in a couple of episodes myself.

Do you know the quickest way to get pegged a troublemaker? A threat, even?

Live as a person of color — a woman of color, if you’re feeling especially brave — and have the audacity to ask for, or — gasp! — expect, equity in the world, and, hoo boy, watch the accusations come. You’re angry. You’ve got a chip on your shoulder. You’re making it personal.

Now, if you create a united front pushing for access into institutions born and bred of inequity, then…countdown until you’re tagged a brown mass of bullies, a threatening mob currently cast as the Latinx authors who’ve called BS on a much-celebrated novel about immigration by a non-Mexican, non-immigrant author. People love to say they want to give “voice to the voiceless” — until the “voiceless” demand to speak for themselves.

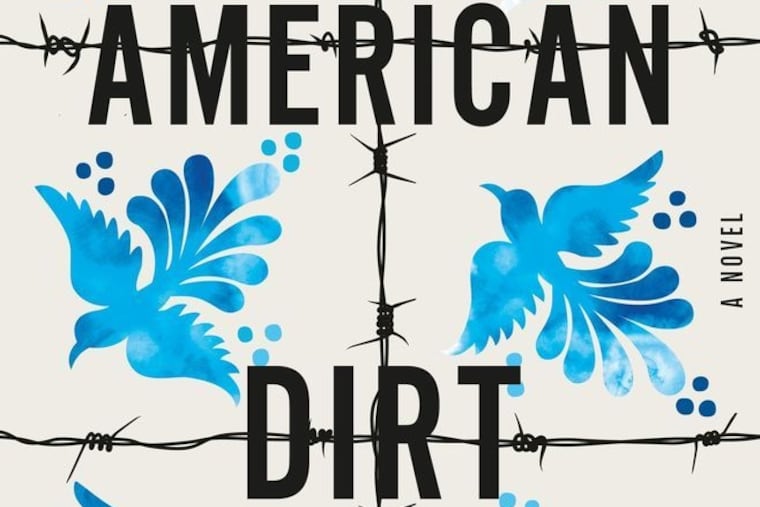

After a drama-filled week or so, the publisher of the controversial new book American Dirt, by Jeanine Cummins, canceled the rest of her tour, citing safety concerns.

I’ve been mildly obsessed with watching the mess unfold, intrigued less with what many have called appropriation — and perhaps worse, not even well-done appropriation — and more intrigued with the marginalized voices of Latinx authors rising up to call out the book industry’s lack of diversity.

These authors didn’t like the book — or even the idea of it — for reasons explored in many fine essays, starting with Myriam Gurba’s scorched-earth critique of the fictionalized story about the Mexican-migrant experience by a writer who identified as white until she recently trotted out her Puerto Rican abuelita. The book, Gurba wrote, belonged to “the great American tradition of … appropriating genius works by people of color; slapping a coat of mayonesa on them to make palatable to taste buds estados-unidenses; and repackaging them for mass racially ‘color-blind’ consumption.” And then there was the piece by the Los Angeles Times’ Esmeralda Bermudez, whose family fled by foot and bus from El Salvador, where right-wing death squads killed and tortured thousands, including several of her relatives.

“The trauma of those dark days shaped everything about me,” Bermudez wrote.

A book by Bermudez, I’d gladly buy.

Authors who joined the chorus were furious with the rigged star-making. The privilege is real, and those who historically have been its biggest benefactors — white men — have a chokehold on it, as my colleague Will Bunch pointed out in a column about the white male rage that fuels the Trump administration.

So, authors whose stories are seared on their souls don’t get to tell those stories, while the publishing world gushes over a woman who dreamed hers up.

It’s easy for many on Team Cummins— which includes some authors of color — to call the criticism professional jealousy. Author Sandra Cisneros defended the book, calling it a start — a little white pill, if you will, that we need to swallow in the struggle for people of color to be seen and heard. News flash: Apparently only white people can make white people care about people of color.

I’ve seen it in my own field, where issues long affecting marginalized communities and long covered by journalists of color only seem to be promoted or prioritized when they affect people who look like the people in power. Another colleague, Solomon Jones, dubbed these changes of heart, when it came to the opioid crisis, the “gentrification of addiction.”

There is a lot to discuss in this controversy — including a promo party for the book in May that featured barbed-wire centerpieces — but gross as that was, it’s almost beside the point.

For their part, a group of authors organizing around #DignidadLiteraria on Twitter responded to the decision to cancel the tour by saying it’s merely a deflection to avoid serious criticism. It does nothing to end structural change.

Now the publisher is proposing a series of town-hall discussions that threatens to wrongly position Cummins as the victim.

“Jeanine Cummins spent five years of her life writing this book with the intent to shine a spotlight on tragedies facing immigrants,” Bob Miller, president and publisher of Flatiron Books, told AP in a statement. “We are saddened that a work of fiction that was well-intentioned has led to such vitriolic rancor.”

So, a couple of things here: Imagine if folks in charge rushed to protect with this much vigor writers of color who routinely get threatened for what they write. Mr. Miller, and every other gatekeeper, has grown accustomed to the status quo. This isn’t vitriolic rancor. It’s a long-overdue reckoning.