Hong Kong crisis has become a crucial test of future U.S.-China relations | Trudy Rubin

Whether Beijing resolves Hong Kong pro-democracy protests by force or through compromise will define China's future relationships with United States and other democracies.

HONG KONG — Impeachment proceedings have overshadowed another riveting drama half a world away: ongoing pro-democracy protests in this iconic city.

Peaceful marches of millions of Hong Kong citizens have given way to violent student protests as Beijing continues to curb the city’s freedoms. Meanwhile, an almost unanimous vote in Congress passed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act this week to support the protesters, as Beijing fumes and a reluctant President Trump decides whether to sign it.

How these protests end — whether in disaster or compromise — will resonate far beyond Hong Kong’s 7.4 million people. Although Hong Kong is a part of China, it is becoming a worrying symbol of Beijing’s attitude toward the rest of the world.

Talks with pro-democracy activists, including students at a besieged campus, left me with one overwhelming impression: This is a self-inflicted crisis by pro-Beijing leaders that never needed to happen.

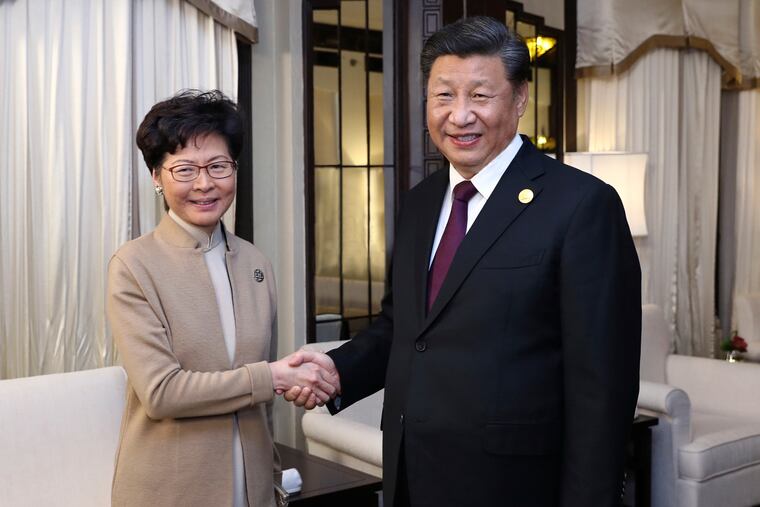

And it has been unnecessarily inflamed by Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s unwillingness to tolerate dissent.

Before the British returned Hong Kong to China in 1997, Beijing signed a treaty guaranteeing the territory would enjoy a “high degree of autonomy for 50 years” under a mini-constitution called the Basic Law. This included an independent judiciary and increasingly free elections.

This “one country, two systems” framework worked tolerably well until Xi came to power in 2012. As China’s limited political freedoms were repressed, autonomy gradually eroded in Hong Kong.

The current crisis began in February, when Hong Kong’s chief executive Carrie Lam introduced an extradition bill that would allow the territory’s citizens to be sent for trial in China, where courts are subject to Communist Party dictates. Nearly one-fourth of the city’s population took to the streets in protest.

What enabled the crisis to explode was Lam’s unwillingness to hold a dialogue with protesters who want to preserve Hong Kong’s rule of law.

She finally officially withdrew the extradition bill in September. But that was too late. Gradually, some student protests turned violent, largely in response to unprecedented police brutality and the arrests of thousands of demonstrators. Student anger has been stoked by Lam’s steadfast refusal, backed by Xi, to investigate police violence.

“Beijing wants to portray the whole thing as a color revolution [the name for popular revolts in Eastern Europe] - all rioters and people pushing for independence,” I was told by Hong Kong’s feisty former government chief secretary, Anson Chan. “But this is about reclaiming freedom and responsibilities we used to enjoy under the Basic Law which Beijing has been steadily eroding. They are creating a whole generation who will harbor anger towards Beijing.”

What makes Hong Kong’s trauma an international problem is the hostility Beijing has displayed toward a different political system. Rather than fire Lam or press her to compromise, Xi has backed her hard line. Beijing officials are now starting to overrule Hong Kong court decisions.

And Chinese leaders have blamed the protests on a supposed “black hand,” meaning CIA support. There is zero evidence of such. Indeed, at one point, Trump, in his eagerness for a trade deal, promised Xi that the U.S. would remain quiet on the protests.

China’s steady erosion of “one country, two systems” has already had major repercussions outside Hong Kong. Beijing wants to impose the formula on nearby democratic Taiwan, with which the United States has close ties and a loose defense pact. Beijing considers Taiwan a renegade province, but Hong Kong’s experience has made Taiwanese citizens more resistant to eventual reunification. Another self-inflicted wound.

On the world stage, Beijing’s allergy to democracy in Hong Kong has broader repercussions. “Hong Kong is a bellwether for the international community as to China’s commitments towards international treaties and what sort of country China will turn into,” says Chan.

Contrary to Beijing’s claim, Congress has a right to express its unhappiness over Hong Kong. It granted the territory special trade status in a 1992 law, on the premise that Beijing would keep its international commitments to allow Hong Kong autonomy for 50 years. The new legislation could eliminate that special status if Beijing shrinks Hong Kong’s autonomy.

“Hong Kong’s position as China’s premier financial center depends on an independent judiciary and rule of law,” says Chan. “But Beijing has an imperfect understanding of what makes Hong Kong tick. Some political liberalization is necessary to sustain the economic system.”

It is this allergy towards Hong Kong’s democratic freedoms that makes Xi’s behavior so unnerving. His inability to tolerate criticism at home or in Hong Kong raises questions about China’s future behavior towards neighboring democracies, as does his disrespect for rule of law.

In mid-August, Trump tweeted he had “zero doubt that if President Xi wants to quickly and humanely solve the Hong Kong problem, he can do it.” Yet many in Hong Kong believe Xi wants the crisis to continue and violence to grow, as a pretext for crushing autonomy altogether.

That would be a much greater self-inflicted wound.