75 years after his death, a lost Philadelphia airman is returned to his family | Mike Newall

“Now there will be proof he existed. That means something.”

Janice Hechler can’t remember the first time she learned that her Uncle Howard was lost.

She was not yet 4 when the bomber plane he had piloted crashed in a lagoon off the Pacific in World War II. Janice didn’t know much about her uncle. As the years went on, the family drifted apart, as families sometimes do.

When she thought of it, she imagined Howard’s life in sepia tones. He had grown up in a family with some standing in Olney, attended the University of Pennsylvania and then enlisted, and was lost. The military had said his remains were unrecoverable. No one in her family spoke about it much.

One day earlier this month, a man in a suit and a woman in an Army uniform showed up at her door in Silver Spring, Md., where Janice, now 77, retired.

After 75 years, Uncle Howard’s remains had been identified. He was coming home.

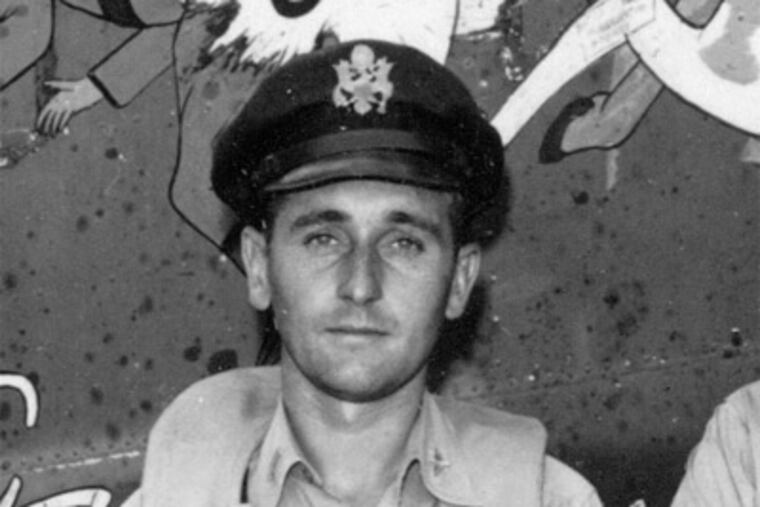

She invited them into her dining room, so they could spread his thick file across the table. Maps and DNA tests. Family letters. Photos of Howard in uniform, the first pictures Janice had ever seen of her uncle.

He looked like such a little boy, she thought.

The story of the search for First Lt. Howard T. Lurcott offers a glimpse into the lengths to which the government goes, even three-quarters of a century later, to send home the remains of those lost.

By the time the military arrived at Janice Hechler’s home March 6, many of the traces of Howard’s life in Philadelphia had faded, too.

Janice offered an outline: Born in 1917, Howard was the second of four children of Alfred and Esther Lurcott. Alfred had made his money during WWI, selling war supplies. By the time Howard went to fight, his parents had moved to Missouri for a new job. (Later, in 1967, in a grim coincidence, Howard’s younger brother, Charles, a naval pilot, died in a stateside plane crash.)

Sitting around Janice Hechler’s table, Michael Mee, chief of identifications in the Army’s Past Conflict Repatriations Branch, filled in more holes.

First Lt. Howard T. Lurcott of the U.S. Army Air Forces was assigned to the 38th Bombardment Squadron. On Jan. 21, 1944, his B-24 Liberator crashed after takeoff on Betio Island, a hard-won airstrip in the Pacific fleet’s island-hopping campaign. All 10 aboard perished. Water in the gas tank caused the crash.

I had to dig to find more about Howard.

Before enlisting in 1942, he had been attending night school at Wharton, according to the Penn archives. He had joined a fraternity: Omicron Sigma Kappa. And school records noted his military standing: A navigation cadet, he had completed his first phase of flight training in Texas. His draft card listed his ruddy complexion and lean build, his brown hair and blue eyes.

After the crash Alfred Lurcott wrote to his son’s commanders and described his flight-school graduation ring: “We have no idea of his effects other than the ring he wore which he greatly prized. I hope that it would be recovered.”

It wasn’t. And for seven decades, Howard’s remains were thought unrecoverable, too.

Back in 1944, nine bodies were pulled from the lagoon, but none could be identified as Howard’s. In the chaos of war, the dead were laid in wooden coffins in a makeshift island cemetery. Airstrips and roads soon displaced graves. Records were lost. In efforts to beautify the cemeteries — and identify the unaccounted for — graves were moved to island cemeteries with sadly evocative names, such as Lone Palm. But sometimes, graves were mismarked, Mee said, or even lost.

As it came out, Howard had come to rest at two locations in the Pacific.

Earlier this year, a portion of Howard’s remains were found in a wooden coffin in a forgotten island cemetery discovered by History Flight, a nonprofit that works with the military to find the unaccounted for of WWII. More of his remains were identified among unknown military personnel reinterred in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu.

Staff Sgt. Carl Shaffer, a 22-year-old gunner and steelworker from Pottstown, was also identified. His remains will be flown to Philadelphia under military honors, his family told me.

For her part, Janice Hechler was surprised by how hard the news hit her.

“It felt like the ceiling came down on me,” she said. “Even though I didn’t know him, I want to make sure everything is nice. I want to do right by him.”

He will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, near his brother, Charles, who rests there on a slight hill.

He will be home.

“Now there will be proof he existed,” she said of the uncle she never knew. “That means something.”