How Joe Biden, Kamala Harris sparked a school segregation debate that’s way overdue | Will Bunch

A presidential campaign flap reminds America of a buried truth: We blew it on school desegregation.

If you grew up as a high school kid in the 1970s (as, ahem, I did) then it would be hard to imagine the day that the debate over school busing to achieve racial desegregation — or, “forced busing,” as opponents masterfully branded it — would not only go away but become largely forgotten.

It was impossible back then to turn on your radio and not hear news reports about a heated debate in some school district from Southern California to New England — most notably Boston, where the launch in 1974 of busing to send white kids from working-class South Boston and black kids from Roxbury across invisible racial lines sparked violent riots.

Ever see what many people think is the most iconic image of a divided America in the 1970s — a furious white protester trying to impale a black civil rights attorney with an American flag? That happened on the inflamed streets of Boston in the glorious Bicentennial year of 1976, and the trigger was a demonstration over school busing. Today, historians like Rick Perlstein have pegged the Boston busing crisis as a pivotal moment in rising white backlash against liberal reforms of the 1960s that carried Ronald Reagan to the White House in 1980, a right-wing counter-revolution that hasn’t ended yet.

One result of that counter-revolution is that what hit America in the 1970s with the force of an atom bomb died in the 1990s and 2000s with barely a whimper — helped by legal rulings from a judiciary heavily shaped by Reagan (who vehemently opposed court-ordered busing) and other conservatives. It took some digging to find an obscure 2009 article from the Philadelphia Public School Notebook and to learn that by the end of the 2000s that “Very little busing for segregation left in Philly.” The response was basically the school-policy equivalent of The Whatever Guy — ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ . Most whites left for the suburbs and private or parochial schools so there was nothing to desegregate (especially when suburban schools would rather touch an electrified third rail than bus their kids across districts lines), and so instead of mandated integration we’re giving our kids “choice” (emphasis on the air quotes) with charter schools.

The result of America’s (and Philadelphia’s) collective shrug is — or at least should be — a national disgrace. Many experts have argued that public schools in the United States are just as segregated by race today as they were in the 1960s — meaning that the real-world impact of 1954′s Brown v. Board of Ed decision that we celebrate with great fanfare every May 17 has been negligible, at best. The great miasma of chatter about school choice and magnet schools and charters has muddied the fact that too many black and brown kids in America go to schools that look too much like the same schools black and brown kids were forced to attend in 1954 — all or almost-all non-white, with crumbling infrastructure and a lack of resources, struggling to attract the best educators.

That’s why it felt like something of a lightning bolt late last month when a series of unlikely events conspired to make school busing, of all things, the flashpoint of the very first Democratic 2020 presidential debates. Those planets lined up because a) the Democratic front-runner is former veep Joe Biden, first elected to the Senate from Delaware in 1972, when he was trying to navigate a white-hot busing controversy in Wilmington and said some things that sure sound politically incorrect in the 2010s and b) Sen. Kamala Harris, looking to stop Biden’s momentum by directly confronting him, summoned her own experience being bused to integrate Berkeley’s schools in the 1960s.

Suddenly, reporters were asking the candidates where they stood on school integration, this political volcano that had sat dormant for decades. Harris — charismatic political shape-shifter that she is — promised what sounded sort of like a return to ’70s-style mandated busing, then walked it back. It’s hard to imagine that a Democratic Party that’s been ruled by fear for decades can summon the political will to again tackle such a thorny issue around race.

But it should.

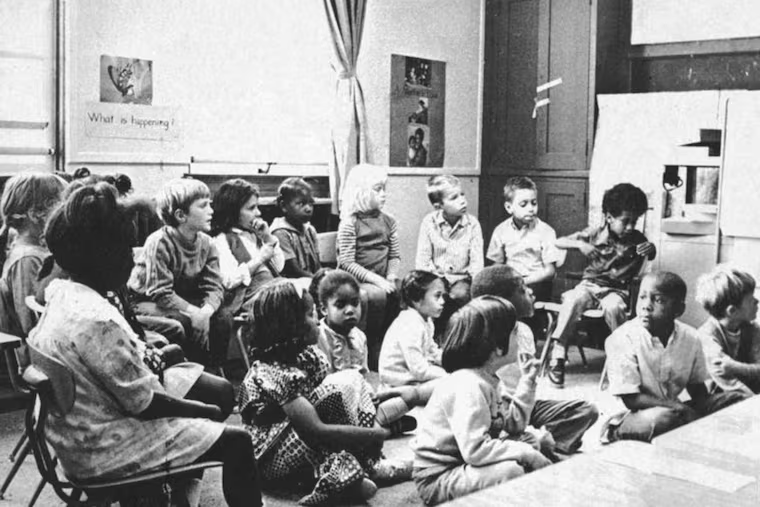

The remarkable thing about the collapse of school busing as school integration tool is that it was achieving what it supposed to do — improving academic achievement for non-whites, in an environment where kids from all races gained the social benefits of interacting with each other.

“Once you got down into the nuts and bolts, it was a success,” Matthew Delmont, the Dartmouth history professor who authored a book called (ironically) Why Busing Failed, told me. He pointed to research by Teachers College’s Amy Stuart Wells and others that kids who attended integrated classrooms did better both in school and in their later careers.

Busing didn’t fail academically but it failed politically. In too many northern cities like Philadelphia and Wilmington, support for keeping “neighborhood schools” became a socially acceptable way of supporting policies that had the practical impact of keeping white kids and children of color apart. A sharp drop in white public-school students has produced some stunning recent numbers on segregation. In California, 58 percent of Latino students attend what the Civil Rights Project calls “intensely segregated” schools. Philadelphia officials testified last month that our schools are currently just 13 percent white in a city where the population is 35 percent Caucasian.

Yet too often the debates about the return of segregation and the sorry state of urban schools — decaying, underfunded, and still struggling to close a racial achievement gap many decades after Brown v. Board of Ed — are, ironically, segregated from each other.

Erica Frankenberg, who directs the Center for Education and Civil Rights at Penn State, agreed with Delmont that a serious new push for more school integration won’t happen without leadership from Washington. “The federal government has always played a key role,” she said. That would include a return to housing policies that encourage better integration of neighborhoods, the most efficient way to ensure that “neighborhood schools” won’t be a euphemism for segregation.

“At the local level, you could see more affordable housing” or a push against zoning laws that prove exclusionary, as Minneapolis has done with its recent move to encourage more multi-family housing, Delmont said. Frankenberg noted state governments like Pennsylvania — divvied up into 500 school districts — could tackle the boundary lines that segregate.

But both Delmont and Frankenberg also noted the federal government fails to use the power of the purse to encourage desegregation. They pointed out that the U.S. Department of Education funding for high-achieving “magnet schools” — often cited as a replacement for mandatory busing to encourage a more voluntary kind of racial integration — is fairly paltry at about $105 million. And federal dollars for even voluntary school busing has been barred under U.S. education law since 1974 — a restriction then supported by a young Delaware senator named Joe Biden.

Although it rarely breaks through the news cycles, the 2020 Democrats have more policy initiatives that would address school segregation than in past election cycles. The most aggressive is Sen. Bernie Sanders’ so-called Thurgood Marshall Plan that would overturn the 1974 law to again allow federal spending on busing, increase magnet-school spending to $1 billion and enforce existing court orders on integration Sen. Elizabeth Warren has joined with Sanders in sponsoring a bill for $120 million in voluntary integration grants, and both Warren and Julian Castro have talked up housing reform. Ironically, Harris doesn’t have an extensive policy, although she has made increasing teacher salaries a cornerstone of her campaign.

Frankenberg told me that it’s hard to seriously talk about school integration in an era of magazine rankings of districts that often revolve around the socioeconomic status of a town’s kids “instead of whether the schools are actually good...the hardest thing when we talk about integrated schools is that we need to broaden our discussion.”

I’d take that a step farther. We live in an era where the politics of racial pot-stirring and immigrant bashing have been wildly, and depressingly, successful, and it’s hard not to think that a generation of kids growing up in their hermetically sealed bubbles of their neighborhood school has got to be a major part of that. Is it coincidence that increased school segregation has gone hand-in-hand with increased hate crime in schools? Maybe it’s time that one measure of student achievement is whether kids are raised to get along with one another. Maybe it’s finally time, some 65 years after Brown v. Board of Ed, to take school desegregation seriously in America.