The Rep. John Lewis Little Free Library is my way to promote ‘good trouble’ | Helen Ubiñas

A Little Free Library to honor a giant legacy.

I’d been thinking about getting a Little Free Library for a long time. Too long.

I’d get giddy whenever I spotted one, relishing the idea of building community with a little box of books. I’d linger as I tried to imagine the stewards behind each one by the volumes they chose to curate.

“One day ... ,” I’d promise myself before walking away with a book or two. (Don’t worry, I always returned with a few: “Take a book. Share a book.”)

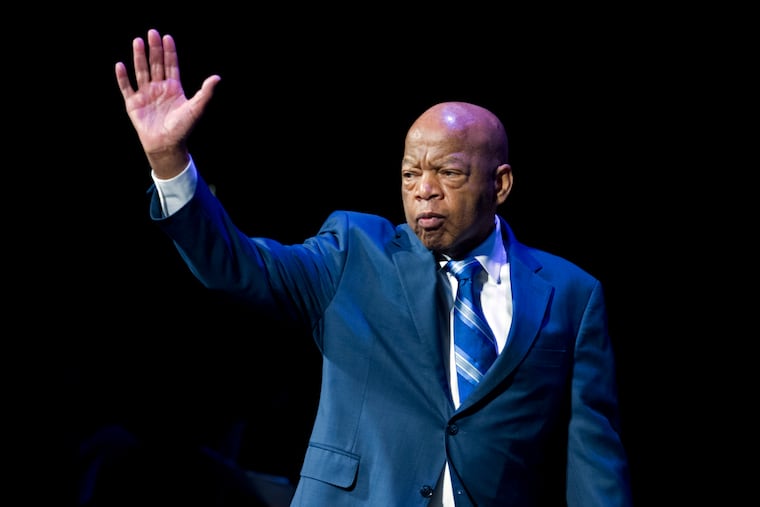

And then the day after Rep. John Lewis died on July 17, I came across a 2016 clip of the civil rights giant accepting a National Book Award for the third volume of his graphic memoir, March.

In an emotional acceptance speech, Lewis was moved to tears as he recalled how as a child growing up “very, very poor” in a home with “very few books” in rural Alabama in 1956, he had been turned away from the public library for being Black.

“I had a wonderful teacher in elementary school who told me: ‘Read, my child, read,’ and I tried to read everything.”

“I love books,” said Lewis.

Watching that while mourning such a profound loss of light and leadership, I knew it was time. I ordered a library in his name that day, plus a plaque to officially commemorate it as the Rep. John Lewis Little Free Library.

And yeah, maybe like some of you out there, I’m desperately seeking signs that things will be OK, but it felt more than coincidental when on the day that I arranged to have the library installed, Lewis gifted the world with his final words.

Not surprisingly, a man who almost always seemed to hit just the right notes in life did the same in death in a posthumous op-ed in the New York Times.

Lewis said that he was inspired in his last days by the reckoning that has swept the country in the aftermath of police killings of Black Americans.

“Emmett Till was my George Floyd,” he wrote, noting that he was just 15 when Till was killed at the age of 14.

“He was my Rayshard Brooks, Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor. ... Like so many young people today, I was searching for a way out, or some might say a way in, and then I heard the voice of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on an old radio. … He said each of us has a moral obligation to stand up, speak up and speak out.”

If you haven’t read the whole essay, you must. In fact, let us not just read this stunning piece, but live it every day.

Lewis’ marching orders are clear.

“Ordinary people with extraordinary vision can redeem the soul of America by getting in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble.”

A few hours later I was watching former President Barack Obama’s passionate eulogy, in which he honored Lewis by reminding us that the late congressman wasn’t just a man of extraordinary wisdom but of extraordinary action.

“You want to honor John? Let’s honor him by revitalizing the law that he was willing to die for. And by the way, naming it the John Lewis Voting Rights Act, that is a fine tribute. But John wouldn’t want us to stop there. …”

It was a vital reminder of all the work to be done.

Count me in.

But for now, may I present the Rep. John Lewis Little Free Library, a very small way to honor a very big legacy.

I’ve got all sorts of ideas for its contents, but for now I’ve begun filling it with books I’ve held on to because of their impact on me, from Claudia Rankine’s Citizen to Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race. I’ve also added local authors: Nicole Gonzalez Van Cleve’s Crook County: Racism and Injustice in America’s Largest Criminal Court and Ink by Sabrina Vourvoulias.

Books that, as Lewis said, might “help redeem the soul of a nation.” Books for and by people who are making that good kind of trouble that I commit to making in this column.

As I write this, I can see someone who has stopped by the library to browse.

It’s hard, but I’m resisting the urge — probably because I’m on deadline — to yell, “Grab a book, and go make some good trouble!”

No promises for next time.