Jared Kushner does it backwards in Bahrain, putting economics ahead of political plans | Trudy Rubin

Without resolving political and security issues, Jared Kushner's economic plan for Israeli-Palestinian peace will go nowhere.

This week the White House finally revealed phase one of its long-delayed Israeli-Palestinian peace plan — the economic phase supposedly aimed at turning the Palestinian economy into the likes of Singapore.

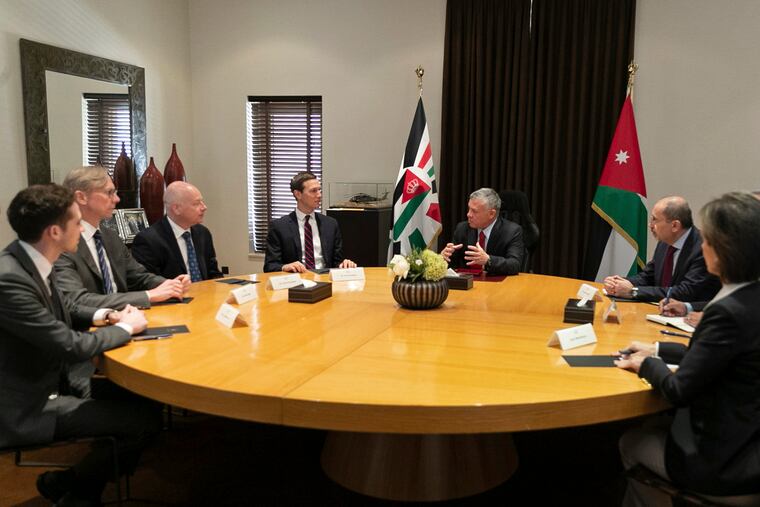

The big reveal came at an economic conference this week in Bahrain. Jared Kushner proposed an international fund for the West Bank, Gaza, and adjacent states to which donors would theoretically pledge $50 billion, half for investments or loans to Palestinians over 10 years.

“Imagine a new reality in the Middle East,” Kushner gushed to heads of fund managers, corporate heads, and international lending agencies and officials from several Arab states. Absent were Israeli officials or their Palestinian counterparts (who are aggrieved at a series of pro-Israeli moves by President Trump).

“Imagine a bustling tourist center in Gaza and the West Bank,” Kushner enthused. “Imagine people and goods flowing securely throughout the region as people become more prosperous. This is not a stretch.”

Not a stretch, but a pipe dream — unless accompanied by a realistic political plan for ending Israeli occupation. And judging by the Bahrain conference, a political plan may never emerge.

I understand Kushner’s desire for “a new reality.” Decades of peace negotiations have gone nowhere. And yes, the Palestinians have missed critical opportunities.

But much of what Kushner is pitching is a rehash of previous economic projects that never gained traction, including 90 pages of specific projects largely cribbed from previous U.S. and international suggestions.

Those plans failed not just, as Kushner claims, because of corrupt or inept Palestinian leaders but for political reasons. Yet Kushner insisted economics come first.

Let’s review a little history: Kushner’s proposal to link the West Bank to Gaza by a 25-mile transit corridor is a concept that has been rejected repeatedly by Israel for political and security reasons. Senior Israeli officials still oppose it.

Ditto for Kushner’s proposed development of gas fields off the Mediterranean shore of Gaza, which could potentially enable Palestinians to finance all their own projects. British Gas, and later Shell, abandoned efforts to develop the field from fear of future conflict between Israel and Hamas; nor was Israeli eager to enable this independent source of Palestinian funding.

As for private Palestinian investment, “the issue [with start-ups] is not money,” says Sam Bahour, a Palestinian-American businessman from Ohio who develops new businesses on the West Bank. He says Palestinian banks have billions of available capital, but “the ratio of deposits to lending is low because the risk is so high.”

Israeli control of Palestinian imports and exports, control of water, and movement of people in and out of Palestinian territories, mean businessmen and farmers often can’t move their goods and workers can’t arrive at their jobs. Expanding Israeli settlements and roads encroach on Palestinian land; they divide the 40 percent of the West Bank supposedly under Palestinian control into separated cantons.

And Israeli control of bandwidth — it took 12 years of negotiations for Palestinians to get access to 3G — holds down the growth of a tech sector. “People don’t get what occupation means to the average businessman or software developer who doesn’t have access to 4G,” says Bahour.

Even a former Palestinian prime minister who attempted good governance — Salam Fayyad, a talented technocrat with high level experience at the International Monetary Fund — was thwarted by occupation. In 2010, in Ramallah, he complained about Israeli checkpoints and restrictions on access to international markets and trade. “Equally harmful are capricious requirements for permits,” he told me, “which means we can’t do things like paving roads or building schools.”

Most harmful, he said, was Israeli refusal, for political reasons, to grant Palestinians permission to use the main access road to Rawabi, a new Palestinian town built by investors from Qatar. With its high-rise apartments and mall, Rawabi was meant to be Fayyad’s signature achievement. Instead, the lack of access delayed the development and sale of apartments for years. When I last visited in 2017, Rawabi still looked like a ghost town.

Fayyad told me then: “Some Israeli officials may talk of ‘economic peace’ as a panacea, but that won’t ever happen in lieu of what needs to happen politically.”

Yet a political solution looks further off than ever. Right-wing Israeli leaders call for annexation of parts of the West Bank, and U.S. ambassador to Israel, David Friedman, says Israel has the right to annex at least some of that territory.

Kushner’s political plan will be delayed at least until November, after Israeli elections. No one knows if it will even deal with Palestinian statehood or hew to the status quo. Or if it will even be delivered.

In Bahrain, Kushner insisted his plan was “a necessary precondition” to a political situation and that Palestinians would be foolish to reject it. Too bad he never spoke with Salam Fayyad.