Five years in, #MeToo speaks to movements built on moments over lifetimes

When all is said and done, we need fewer progress reports and more progress.

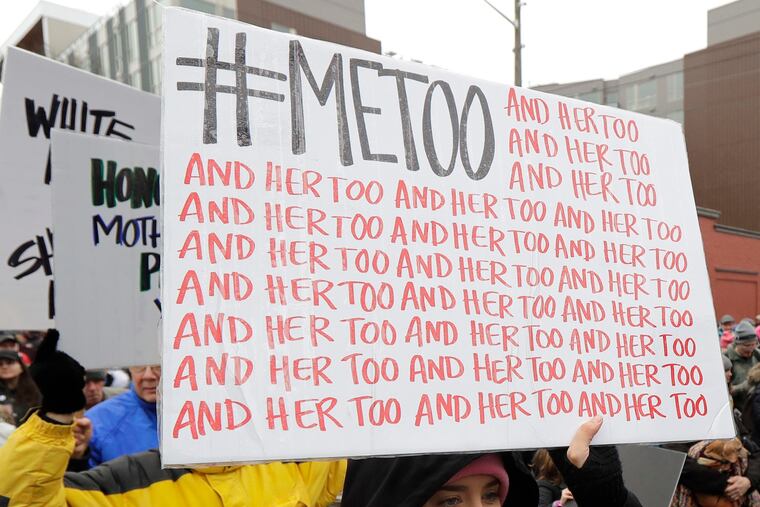

Five years ago, #MeToo ignited a global reckoning.

And with the anniversary comes a seemingly endless debate assessing its impact — which, like most reckonings, is mixed at best. Take these recent headlines, for example:

#MeToo, 5 Years Later: Survey reports employees still experiencing abuse, and harassment in Hollywood.

Five years after it took off, around half of Americans support the #MeToo movement.

Five years on, some French feminists wonder if #MeToo has gone too far.

I happened to be wading through a slew of these stories when a new federal report on another movement I care deeply about was released — and its results weren’t good.

Latinos remain grossly underrepresented in the media.

In the latest of two reports commissioned by Congressman Joaquin Castro (D., Texas), the Government Accountability Office found that Latino representation in TV, film, and media grew by only 1% in the last decade. The report also showed that even though Latinos make up 18% of the U.S. labor force, they are just 12% of media professionals and 4% of the industry’s managers.

Latinas — who make up just 3% of jobs in the industry when you exclude service positions — are especially affected.

“It’s distressing that we are still talking about this issue of Hispanic media underrepresentation,” Sonia Pérez, acting CEO of the Latino nonprofit advocacy organization UnidosUS, said during a news conference at the National Press Club in Washington on Wednesday.

“Nearly 30 years ago, UnidosUS … documented the virtual invisibility of Latinos in the media,” she continued. “We noted that ‘it was easier to see an alien from outer space than someone Hispanic’ onscreen. Three decades later the GAO report found that the media industry continues to lag behind virtually every other industry when it comes to Latino representation.”

Pérez was right; it is distressing — depressing, really — though not at all shocking when you consider that more than 50 years after the historic Kerner Commission Report called for the hiring of more Black journalists, they remain inexcusably absent from many newsrooms, including mine. (The criticism is justified.)

But the report also offers a reminder about the excruciatingly slow road to progress, whether we’re talking about racial representation in the media or the protection of women in the workforce, and all the intersecting causes in between.

Because despite the movement or the hashtag, the truth is that these efforts — #MeToo, Kerner, Unidos — are variations on the same theme: being seen and heard in the pursuit of equity, representation, justice, and accountability.

One more very important thing: We need to acknowledge and support those who’ve long carried the weight of this pursuit. The success, short- and long-term, of many of this country’s most consequential movements is most often due to the tireless and often erased work of Black and brown people.

#MeToo burst into our social consciousness in 2017 with a viral tweet from actress Alyssa Milano, who’s white, but the movement was founded years earlier (in 2006) by Black activist Tarana Burke to help Black women who suffered sexual abuse.

And while many words are being dedicated to debating the movement’s success, those who were in the fight way before it became a Hollywood hashtag, and those who have remained long after, have a different take.

“It’s up and down and up and down all the time,” Burke told the New York Times in a recent interview.

One high-profile down: the defamation trial between actors and ex-spouses Amber Heard and Johnny Depp over an op-ed she wrote for the Washington Post in 2018 where she referenced her experience with domestic violence. Even before online mobs decided an imperfect woman could never be a victim and a jury decided the case mostly in Depp’s favor, many were declaring the end of #MeToo.

But that ignores some pretty major ups: Powerful and famous men have had to answer for their behavior, even if only temporarily. And, perhaps more important, multiple states have also passed laws to make workplaces safer.

And it is that space in between where progress should be measured, Black-Puerto Rican organizer and journalist Rosa Clemente told me when we spoke this week.

Clemente, a veteran organizer who is completing a doctoral dissertation on national liberation struggles, said anything else is “just noise.”

No matter the movement, there will always be backlash, a painful pendulum. There is no better example of that than the mass police reform effort that mostly went nowhere after the death of George Floyd in 2020. And there may be no more striking reminder that no victory is necessarily permanent than the Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade this summer.

The key to any sustainable movement, Clemente said, is not allowing the focus to be derailed by its visibility — even if that visibility amplifies the movement.

“We’ve seen hashtag movements blow up and then implode,” she said, adding that #MeToo isn’t one of them. “We know the difference between visibility and the work necessary to reach the people who need it.”

Burke has recently launched Survivor’s Sanctuary, a digital platform for survivors of sexual assault.

All of this talk of measuring impact brings to mind the late Congressman John Lewis’ quote about the fight for equity and social justice:

“Ours is not the struggle of one day, one week, or one year,” he famously said. “Ours is the struggle of a lifetime, or maybe even many lifetimes, and each one of us in every generation must do our part.”

It is a righteous sentiment, but I’d be a hypocrite if I didn’t also point out how hard it is to live by that creed, how painful patience can be. How I’ve tapped out on movements that mean a lot to me, exhausted and enraged by the glacial pace of progress, in search for other avenues to make some difference.

I’m tired of progress reports. I want progress.

When I shared my frustration with Clemente, she was sympathetic: “Challenging systemic inequality” is hard and heartbreaking, she said.

Disappointment and anger, she reminded me, come with the territory.

And so perhaps, if we must assess the impact of the viral #MeToo moment five short years in, that is how we should measure its success: That in these struggles of our lifetime, there is some space in between the ups and downs where we can see some progress.

It’s a reminder that change is still possible, as long as we can muster energy enough to seek out a salve for our pain and our anger. For better or worse, those fighting hardest still have plenty of both.