Slavery is a part of the history of Philadelphia’s suburbs | Opinion

We need to reckon with a history that’s hidden in plain sight, writes Colin McCrossan.

When Jack escaped from his enslaver, John Morgan, on Sept. 24, 1770, he left Radnor Township with only the clothes on his back. We know a few things about Jack from an advertisement that John Morgan placed in the Pennsylvania Gazette: Jack was around 27 years old. He had been enslaved by John Morgan for 11 years. He wore a felt hat, homespun cloth jacket, shirt, and pants when he ran away.

Morgan offered a reward of 30 shillings for his capture. We don’t know how long Jack was free, but it’s likely he was recaptured because Morgan’s mother, Magdalen, placed an ad in the same paper in 1773 selling an enslaved man who matched Jack’s description.

Today, the land that once was John Morgan’s farm is Villanova University’s main campus, where I am a graduate student in the history department. I think about Jack’s life often as I walk to class. Crossing Lancaster Avenue, which didn’t exist in 1770, I imagine his daring escape.

White people enslaved Black people for more than 100 years in Philadelphia’s suburbs, mainly in the 1700s, but you won’t read this in a textbook or see any historical markers about it. Why? Few historians have researched this history in depth. For most people, thinking about slavery means imagining a Southern cotton plantation. In reality, the history of slavery is enmeshed in Philadelphia’s suburbs.

For the last year, I have worked as a researcher for The Rooted Project, Villanova’s initiative to study its past and the history of slavery in Philadelphia’s suburbs. I’ve researched the histories of both enslavers and enslaved people whose stories haven’t been told.

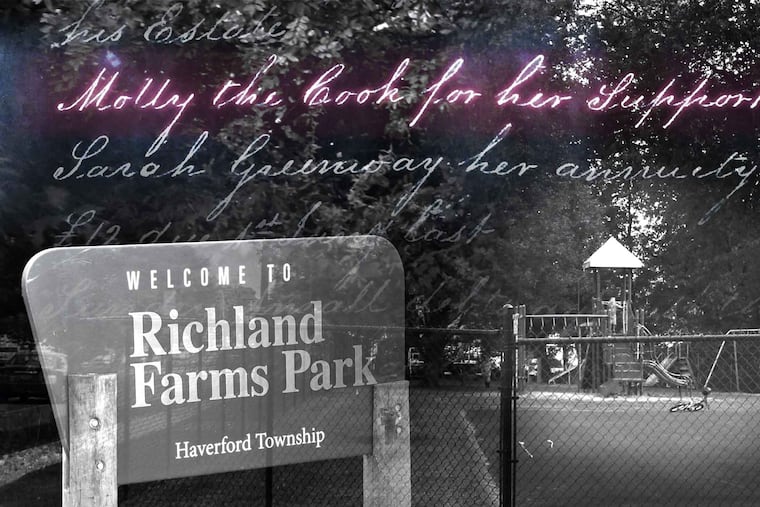

Consider Molly Richardson, a Black woman who was enslaved by the white lawyer Richard Willing in Haverford Township. She left Willing’s estate — called “Richland” — when she was freed but returned in 1799 to work as a paid cook for Willing’s wife, Margaret. Richardson also rented a room from another free Black woman in the area.

Today, Richland Farms Park, where families meet and kids play basketball, is located in the space where “Richland” once was. Knowing this history, I find it disturbing to walk through the park. This space has a violent past, and no trace of Molly’s life.

But I’ve gotten to know Molly, or at least part of her story, through my trips to the Delaware County Archives and digital searches on Ancestry.com. She was a human being. She had hopes and dreams — and she was enslaved. What does it mean when we walk through Richland Farms Park and nobody knows about Molly? Her life matters.

The erasure of Black people from public space and history is part of a larger problem. Our schools and governments have failed us by ignoring the history of slavery. It’s a national story that also happened here.

Polling has shown that Americans are under-informed about the history of slavery in the United States. A 2019 Washington Post-SSRS poll indicated that 46% of adults incorrectly believed that Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation ended slavery in 1863. In fact, slavery was outlawed by the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which passed in 1865.

The Southern Poverty Law Center has also shown that K-12 school curriculums don’t contain accurate or sufficient information about the history of slavery. As a result, students lack basic knowledge of the role slavery played in shaping our country and the impact it continues to have on race relations. In a moment of renewed national resistance to teaching all of U.S. history and rampant book-banning, students, staff, and parents are likely to learn even less.

But slavery is a part of the Philadelphia suburbs’ history. Suburban residents must acknowledge this history, tell the truth about it, and have frank conversations about how enslaved people contributed to their communities. We need school boards that champion accurate and inclusive curriculums, faith organizations that host public events, and local leaders that insist on sharing this history with their constituents.

I envision a future in which Philadelphia’s suburbs are dotted with plaques, statues, and public artworks that memorialize enslaved and free Black people like Molly Richardson and Jack who struggled to survive in an unforgiving world.

We must make this hidden history visible for all.

Colin McCrossan is a graduate student in the department of history at Villanova University, where he works on The Rooted Project, an initiative exploring Villanova’s connections to slavery, segregation, racism, and gender discrimination.