A Conshohocken financial exec and his wife help ex-prisoners find jobs. This is true Christianity. | Maria Panaritis

A Conshohocken financial wiz and his wife are living an in-the-trenches ethos of helping people that has gone out of vogue in our age of acrimony, resentment, and hoarding of wealth.

George and Mimi Limbach left their Drexel Hill home Wednesday morning and headed not to George’s job as a financial advisory firm executive in Conshohocken, not to visit any of their six grown children, but to a warehouse a half hour away that they rent in Philadelphia’s Germantown section.

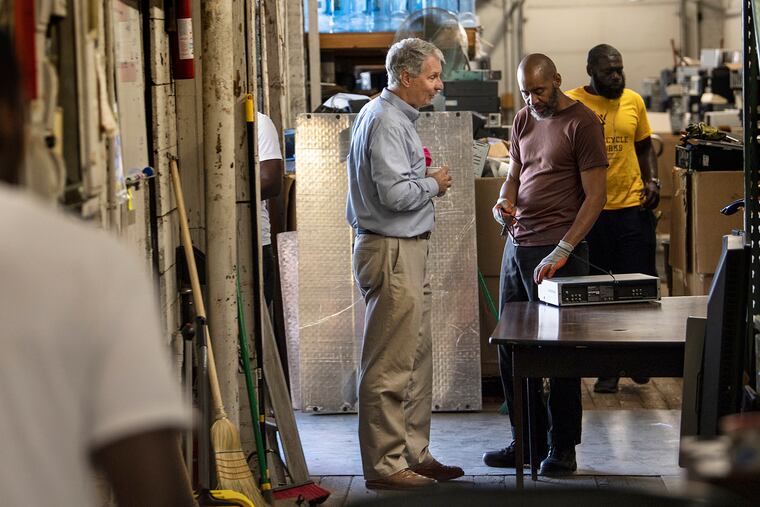

At 8:30 on the dot, George, 66, and Mimi, 65, sat in two of about 20 mismatched chairs in a circle inside a cramped room inside PAR Recycle-Works on East Walnut Lane. Then, over coffee and doughnuts, 11 former prison inmates spoke about “accountability.”

“I don’t blame nobody,” said 30-year-old Al Butcher, who did time on a burglary conviction while on drugs and while trying to provide for his two kids and the two children left behind by his dead brother. Al would soon be on the warehouse floor, taking apart old computers being scrapped by law firms, schools, and municipalities for $12.20 an hour. No one would be judging anyone else. Everyone there had made terrible mistakes but were now in search of a new way.

“I can’t change what I did," Al said. "I can only change what I’m doing now. Better myself moving forward.”

Most people, even those who proclaim themselves devout Christians, don’t bother to sweat while giving back to the world — if they give back at all. But the Limbachs have rejected the caustic hypocrisy of our age, in which far too many are complicit in denigrating the poor.

The Limbachs are living an ethos of helping people and doing so in the trenches. It is a striking humanism that has gone out of vogue in our age of acrimony, resentment, and hoarding of wealth. I heard about them from a former professor of mine who knew them in Narberth, where they raised their kids before moving to Drexel Hill.

“I was ruined by the Jesuits,” George jokingly told me in assessing how, the son of a blue-collar Bayside, Queens family, he went down this path. He was the first to attend college. But first he won a scholarship to Regis High School in Manhattan, where, as anyone who’s attended a Jesuit school can attest, he learned that serving others in need is as important as mastering prep-school calculus.

Mimi recalled childhood bike rides to the Connecticut prison near her home, and Catholic mission magazines that her devout grandmother often had around. All presented portraits of poverty that touched her at a young age and stayed with her.

She worked for 18 years at St. Joseph’s University and raised her kids. She put degrees in nursing and pastoral care and counseling to work in more recent years as a volunteer behind prison walls. It was at Philadelphia’s Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility that she met a woman who now serves on PAR’s board , Laura Ford, a former longtime director of prison ministry for Philadelphia’s Catholic archdiocese.

Ford, who has been seminal in helping get this $750,000 nonprofit off the ground, told me about one of her own unforgettable moments in prison. It was an exchange between inmates at Graterford Prison and the late Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua, who was in charge of the Philadelphia Archdiocese at the time.

“One of the lifers stood up at the end and asked if the church could help with the issue of life without parole,” she said. Bevilacqua was mute. But Ford? She called the prison chaplain and asked to meet with the lifers, a group who develop a monastic spirituality due to their isolation and life sentences. “I was so impressed by them.”

Former felons cycle in and out of the Limbachs’ recycling nonprofit every few months. Recently released inmates are there just long enough to adjust to the demands of a job and gain a foothold in the “real world.” Then they are placed with more permanent employers. Four years after starting, the Limbachs say many more stay employed than return to prison.

The weekly group talk session - run by none other than a former inmate who now helps run the place, Maurice Jones - reminds everyone of their human frailty and untested determination. There’s another message, too: You will always have help as long as George, Mimi, Maurice — and all the others there — are alive and connected to this special place.

“You’re brothers and sisters to us," George told the group warmly. “We want nothing less than for all of you to be successful.”

The Limbachs started this business after Mimi, as a volunteer at Graterford Prison, came to see just how many inmates worked hard to get out, only to return a short time later.

Most are released with little more than bus fare, so they return to dangerous addresses and routines. Many ended up inmates in the first place after deeply troubled childhoods with unstable or absent families. PAR delivers a mostly unappreciated predictor of success in life: a support network.

George not only spends time at the warehouse before heading to work at Compass Ion Advisors in Montgomery County, but he plows some of his annual earnings into its budget. He and his board also hustle to find institutions with old computers to ditch. It’s their lifeblood.

They’d love donations of equipment and cash. This would help them expand. But more immediately, their only box truck was totaled under an overpass a few weeks ago. They easily need $50,000 to buy a used one.

The Limbachs have put their words to deeds; We would all do well to do the same.