Daughter of a paralyzed gunshot survivor pens a children’s book to help families through trauma | Helen Ubiñas

The National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center estimates as many as 45,000 Americans have been paralyzed from gunshot wounds. Bottom line: This book could help.

I’m always on the lookout for resources that might help a support group for paralyzed gunshot survivors with whom I admittedly have a special relationship.

Nearly two years after they formed out of necessity, it’s still a struggle for many members of A Wheel Family to access basic aid for themselves and their families.

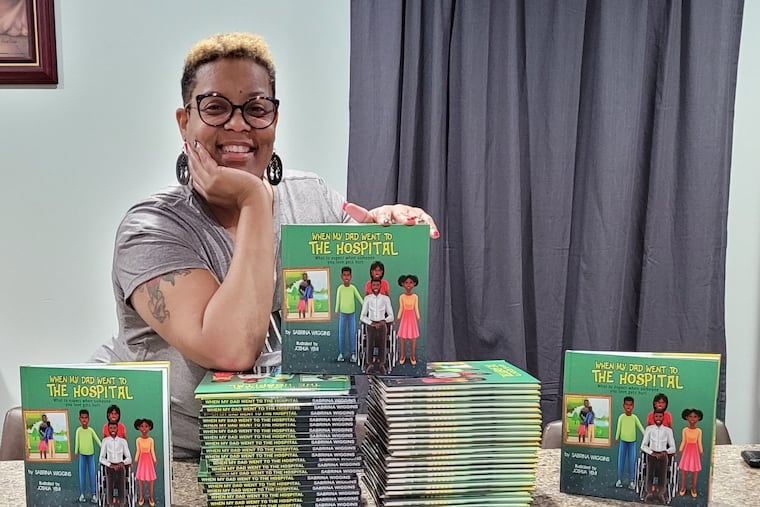

So, when I got an email from Sabrina Wiggins about her new book for young readers whose loved ones have been shot and paralyzed, I thought: Maybe this can help. Several of the members are parents.

Wiggins, 44, a financial analyst for the U.S. Department of Defense, lives just a few hours away in Maryland.

She was in third grade when her father, Benjamin Wiggins, was shot and paralyzed. But it wasn’t until she was in therapy decades later that she realized she’d never confronted the lingering trauma.

“I went back to that time and place, and realized how much of the things that I’ve done since were affected by that time in my life,” she recalled when we spoke.

So, Wiggins, a mother and grandmother, did what she often does when working through her emotions: She wrote about them, and then turned them into a self-published book. (It’s marketed as a children’s book, and can certainly be read to them, but it read to me more as one for teens and young adults.)

When My Dad Went to the Hospital is based on Wiggins’ experiences coping with tragedy at a young age.

In the book, the young narrator, Serena, and her brother, Benny, are just a couple of days into their new school year when their lives are shattered by their father’s shooting.

“It turned our world upside down,” Wiggins said.

Wiggins’ father, now 67, was shot by a girlfriend’s ex-boyfriend, Wiggins said. The injury paralyzed his right side and affected his ability to speak.

Wiggins doesn’t spend a lot of time writing about the specifics of the shooting, instead choosing to focus on the aftermath of tragedy and trauma.

“Learning how to cope with such an experience is not something that many parents or guardians are equipped with, and I think that it is important that both adults and children get the counseling they need,” she said.

An estimated 300 people in the United States are shot every day, with about 200 surviving with life-altering injuries, according to data from the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.

Years after my colleague David Gambacorta and I wrote about those who are shot and forgotten, the numbers of paralyzed survivors are still incomplete because most hospitals don’t specifically categorize or track this type of injury.

But even the available data are stark: The National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center estimates as many as 45,000 Americans have been paralyzed from gunshot wounds. In a first-of-its-kind report released in 2020 by the Philadelphia Public Health Department that sampled 2016-17 shootings, one in seven city shooting victims ends up paralyzed in some way.

Bottom line: Wiggins’ book would resonate with many families. Too many. It’s currently available on Amazon, but if any librarians are listening, it would be a valuable book to get into neighborhood libraries, trauma hospitals, and victim service organizations.

Wiggins recently invited members of the local support group for paralyzed gunshot survivors onto her podcast highlighting those impacted by violence. They talked about the book.

Among those she interviewed was one of the group’s founding members, Leon Harris.

Harris was a 17-year-old honor student when he was shot by robbers as he walked home from his job in 2007. Now he’s a husband, and he and his wife, Tierra, are parents to a 3-year-old daughter, Noel.

Noel has asked about his legs, he later told me. And his responses have been some variation of: “Daddy was hurt by a bad man. He can’t run and jump and play like you can, but he makes the best of the situation and we’re still gonna have fun.”

It’s enough for now, but he knows there will come a day when she’ll need more, and Wiggins’ book can help. (She already likes the illustrations by Joshua Yemi, he told me.)

“I think it all goes back to awareness,” he said. “Anything that helps bring awareness is necessary. There’s peace of mind knowing there are people out there in the community who have been through this, and it’s unfortunate to say, but with what’s going on out there, there will only be more.”