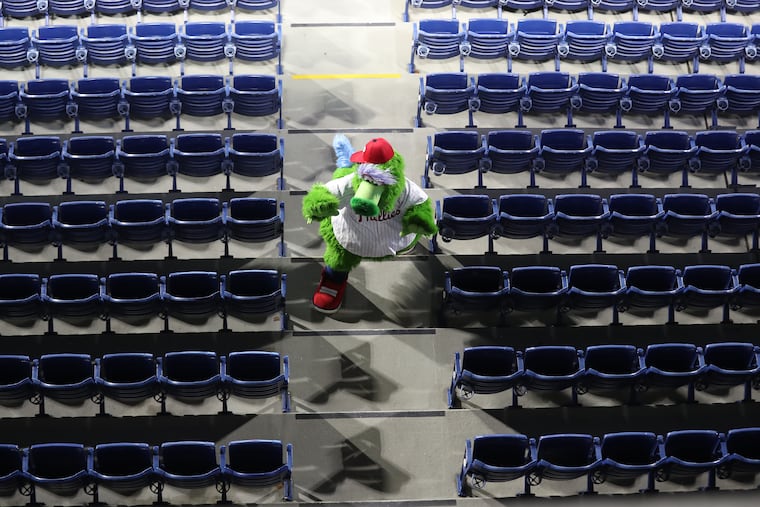

Major League Baseball couldn’t do a bubble. Can players be more disciplined to save season from a coronavirus crisis? | Scott Lauber

With the baseball season in peril, it’s becoming clear that a "bubble" was the best way to get sports back up and running. But the bubble wasn't a practical solution for MLB.

Now that the Phillies have gone back-to-back days without a positive test for COVID-19, now that they know the two positives Thursday were false readings, and now that they have been cleared to finally resume playing this week, can they really jam 57 games into 56 days to complete their 60-game schedule?

“I think we’re more concerned about just Monday,” manager Joe Girardi said Saturday. “Can we just get through Monday?”

The same question has arisen at Major League Baseball headquarters in New York.

If, as commissioner Rob Manfred said last week, more than half of the Miami Marlins' roster becoming infected with the coronavirus didn't qualify as a "nightmare" scenario for baseball, then surely the subsequent events of the last week have left him sleeping with one eye open.

MLB has more than just a Marlins problem. Additional members of the St. Louis Cardinals’ traveling party tested positive Saturday, one day after two players came down with COVID-19 while on the road in Milwaukee. Sixteen games were postponed last week. Six teams -- 20% of the sport -- didn’t play Saturday because of the coronavirus. Injuries, particularly to pitchers, are spiking because of the short ramp-up to the season and the stop-and-start schedule. And doubt is increasing that pandemic baseball can be played successfully in a non-bubble environment.

It’s little wonder, then, that Manfred contacted Players Association executive director Tony Clark on Friday, according to ESPN, to warn him that MLB might have to suspend the season this week if players aren’t more diligent about following health and safety protocol to curb further spread of the virus.

» READ MORE: Rob Manfred says baseball season in jeopardy as coronavirus positive test results turn MLB schedule into chaos

“The most important thing is that we’re all really responsible, we pay attention to where we are, when we’re there, who has masks on around us,” Girardi said. “Don’t take chances.”

But what if baseball, like the country at large, lacks the discipline to get the virus under control?

The Phillies held only their second workout in six days Saturday at Citizens Bank Park, with players reporting to the field at staggered times. After not playing since last Sunday, the team has health concerns that don’t involve an infectious disease.

“The players aren’t playing baseball right now and they are used to playing almost daily,” general manager Matt Klentak said the other day. “That presents its own health risks -- maybe not COVID-related, but orthopedic.”

It seems far-fetched -- even with a slew of doubleheaders featuring seven-inning games, a rule agreed to last week by MLB and the players’ union -- that the Phillies will play 60 games.

(Side note: Seven-inning games would be one way for the Phillies to minimize the impact of a bullpen that went from a training-camp concern to a train wreck in the first weekend of the season.)

But every team doesn’t have to play 60 games. Girardi is advocating for playoff spots to be determined by winning percentage. It happened that way because of work stoppages in 1981 and 1972, and it probably will happen again -- if baseball can even reach the finish line.

MLB officials were optimistic 10 days ago. During the intake-screening process at the outset of training camp, MLB reported 66 positive tests (58 players, eight staff) out of 3,748 samples, a 1.8% rate. From that point through July 24, there were 29 positive tests (22 players, seven staff) out of 28,888 samples, a 0.1% rate.

But that was before the season opened, when teams were mostly contained in their home cities and playing intrasquad games. As Phillies pitcher Jake Arrieta said on July 22, “There’s still going to be some uncertainty as we start to travel and play real games against different teams in different cities.”

Those concerns proved to be valid, which begs the question of whether MLB was wise to stage a season with teams based in their home ballparks and traveling regionally between cities rather than adopting the “bubble” model used by the NBA, WNBA, and MLS or the NHL’s “hub cities” approach. The NFL, which is also planning to keep teams in home markets, is surely paying close attention to baseball’s predicament.

» READ MORE: Marlins using sleeper buses to transport their coronavirus-infected players from Philadelphia

All along, many health experts believed the “bubble” offered a better chance for success. In May, Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, chairman of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, suggested a gradual approach to returning to the field that began in a quarantined environment and expanded outward.

MLB flirted with the bubble concept. One idea involved isolating all 30 teams in Arizona and playing games at Chase Field in Phoenix and a dozen nearby spring-training facilities. Another brainstorm called for an Arizona/Florida split, with teams using spring-training facilities. A third would have brought Texas into the mix and established hub cities.

Players balked at leaving their families during a pandemic. But there were other reasons why a baseball bubble was impractical. Arizona is oppressively hot in the summer, especially for outdoor games. Unlike the NBA and NHL, which will swiftly eliminate teams from their bubbles as the playoffs begin, MLB would’ve needed to quarantine 30 teams -- at least 900 players, plus coaches and staff -- for more than three months.

“The numbers of people involved and the numbers of people to support the number of players was much, much larger in our sport,” Manfred said in an MLB Network interview last week. “The duration would’ve been much longer, and the longer you go, the more people you have, the less likely it is that you can make the bubble work.”

Oh, and COVID-19 wouldn’t have cooperated, either. Over the last few months, the virus has spiked in Arizona, Florida, and Texas, the three states that have enough suitable ballparks.

“It’s spreading at an alarming rate, so I don’t know if you move somewhere for a week, will you have to move somewhere three days later again?” Girardi said. “Now, all of a sudden, there are 10-15,000 cases in that state. I think it’s just being careful what you do no matter where you live. I don’t know if there is a place to go. I really don’t. I wanted to know if they had a league in Iceland. That was my question.”

» READ MORE: The Phillies should opt out of this crazy COVID-19 baseball season | Bob Brookover

Baseball is left, then, to press forward, leaning on its 113 pages of protocols and making adjustments along the way. Two changes after the Marlins’ outbreak: MLB will mandate surgical masks instead of cloth masks on the road, and every team will appoint a compliance officer -- a hall monitor, of sorts -- to make sure members of the traveling party follow the rules.

As ever, it boils down to personal responsibility. It’s baseball’s only chance to make this work.

“I got in an elevator the other day and someone started to get in without a mask, and I just said, ‘No,’” Girardi said. “I just said, ‘Sorry.’ I don’t want to be rude, but I have a responsibility to our game that I don’t contract it and spread it around. That’s how everyone has to look at this.”

If only everyone would.