Philly’s Dick Perez is still the ‘Diamond King’ 40 years later. Here’s how he earned his title.

Perez is now known as baseball’s preeminent artist, but for many fans, he was the illustrator of their summers.

The letters — “hundreds of them,” Dick Perez said — come from adults who grew up collecting baseball cards in the 1980s, wanting to tell him how much they loved his work when they were kids.

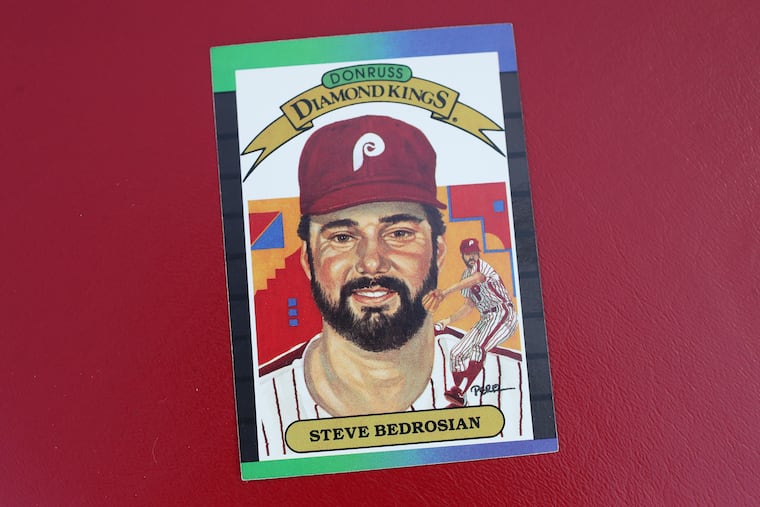

Perez is now known as baseball’s preeminent artist, but for them he was the illustrator of their summers. Perez painted portraits every fall in his suburban Philadelphia studio of the game’s biggest stars and his work was printed each spring by Donruss in its annual Diamond Kings series.

The first cards — which reintroduced artwork to the trading card industry — appeared 40 years ago and featured everyone from Mike Schmidt to Ken Griffey Jr. during a 15-year run using Perez’s work. The artist even painted a self-portrait for a card in 1994.

But he never heard anything from Donruss. No feedback, no critiques, no questions when he changed the styles of the portraits. It felt almost like he was painting them for himself, leaving Perez to wonder who was even collecting the cards. And then — decades later — the letters arrived.

“And that was so rewarding,” Perez said. “It’s great. Finally.”

» READ MORE: David Robertson’s road back to the Phillies included a stop in a Rhode Island men’s league

Perez was the official artist of the Baseball Hall of Fame, his artwork appears in two presidential libraries, and he was a regular tennis partner with Ted Williams. But for a generation, the Edison High graduate will always be the artist behind Diamond Kings. The annual series — usually about 25 cards — was included in each Donruss set just as the baseball card industry exploded in the 1980s.

A 1981 lawsuit ruling ended Topps’ nearly 25-year run as the exclusive baseball card maker, paving the way for Donruss to score a license to print cards with players’ likenesses.

But the company did not have much experience with sports cards as most of its business was made in producing trading cards for Hollywood movies. So Donruss asked Bill Madden, a New York sportswriter hired to write the descriptions on the backs of their new baseball cards, what the company could do to set itself apart. He suggested calling Perez.

Bringing back artwork

A year later, the first Diamond Kings set was printed with Pete Rose as card No. 1. The cards were a throwback to Perez’s youth in Harlem when he emptied his pockets every spring to buy new packs on his way home from school. Some of the cards, he remembered, were hand-painted, so perhaps bringing back artwork could set the Donruss cards apart.

Perez would not be able to paint every player, instead offering to paint a series of stars every season.

“Frank came up with the idea,” Perez said of his late business partner, Frank Steele. “In the 1930s, there was a subset of baseball cards called Diamond Stars. We wanted to do something similar. We would decide who would be the subjects and make our decisions in the middle of the season for the following season. I had to paint them, obviously, so I needed a head start.

“Each one took a couple days. They would send you one photograph and I wanted a lot of photographs to choose from. I wanted to control the image, not just painting a picture of something someone handed me but something I would choose. This was before the internet, so I bought magazines and 400 baseball books. I would just look for images and often choose something that they didn’t even send me. The biggest chore was just getting the image.”

Perez moved to North Philadelphia when he was a teenager after his stepfather took a job as a porter for a bus company. He attended the Philadelphia College of Art at night while working in the day at a sporting goods store and as an art studio’s delivery driver. He said his work ethic — “If you worked hard and worked until 3 o’clock in the morning most times, you’ll be successful,” Perez said — came from growing up poor.

“We weren’t starving,” Perez said. “But there were nice things happening in the world that I became aware of, and I would have liked to be a part of that other part of the world, so it was an ambition to have a good life and to be able to educate and pay for colleges for kids and live in the country and have my studio. It was just ambition. If you have that, you have a lot.”

He worked for the Eagles, was the Phillies’ official artist for more than 30 years, and has painted portraits of every Hall of Famer. He now lives in Brooklyn and his art studio is just two blocks from where Ebbets Field once stood. He grew up dreaming of being a big leaguer before finding a career that turned the greats into art.

The Hall of Fame presented President Ronald Reagan at a White House luncheon with a portrait Perez painted of Grover Cleveland Alexander since Reagan portrayed the pitcher in a movie.

“So he owns it,” Perez said. “And we did the same thing with Bill Clinton. But what the hell did Bill Clinton have to do with baseball? He didn’t play any. But Arky Vaughan came from Arkansas and that was our tie-in, so we did that. Two presidential libraries have paintings. That’s what official artist of the Hall of Fame meant. It was cool.”

Competitors follow suit

What once seemed radical about Diamond Kings is now a staple of the industry as artwork has become commonly intertwined with baseball cards. Upper Deck had artwork cards in its 1990s sets, Fleer made its baseball cards look like comic books in the mid-1990s, and Topps runs an annual limited series that allows artists to reimagine historic cards. Perez even painted a few series for Topps after his run of Diamond Kings ended. Almost every brand, just like Donruss did 40 years ago, has used artwork to set itself apart.

Perez’s first Diamond Kings set was straightforward: a portrait of each player behind a painting of that player in action. But each year — as Perez kept hearing silence from Donruss — the cards evolved. The 1996 set — the final year of Perez’ Diamond Kings — is nearly indistinguishable from the 1982 cards.

“I got tired after a while of doing the straight-up portraits,” Perez said. “So I started changing the background and doing full figures and just doing crazy things for my own fun. They never had any comments about my work. They thought it was art and that it was OK.”

» READ MORE: Chase Utley has moved to England to spread the gospel of baseball — and he’s already converted one Brit

Perez’s experimentation made each year worth collecting, something he would not know until he opened those letters. Some of the fans ask for an autograph. Others tell Perez how much they enjoyed Diamond Kings. And others have become artists, just like Perez, and wanted to know how he became the Diamond King.

“They can’t believe that there’s a place in society for someone like me, who loves the game and can paint them,” Perez said. “They want to know how I did it so they can do it. But it doesn’t work that way. Everything was serendipitous. Everything came from meeting the right person at the right time. You have to perform, but you have to be lucky.”