Hank Aaron, who overcame racism to become baseball’s home run king, dies at 86

Hank Aaron, who faced death threats and racism while chasing down Babe Ruth’s home-run record in a memorable pursuit that captured the attention of the country, died Friday morning. He was 86.

Hank Aaron, who faced death threats and racism while chasing down Babe Ruth’s home-run record in a memorable pursuit that captured the attention of the country, died Friday morning. He was 86.

Mr. Aaron, who started his career as a teenager in Negro Leagues, held baseball’s home-run crown for 33 years before his career mark of 755 homers was eclipsed in 2007 by Barry Bonds. Mr. Aaron was not just a slugger but one of baseball’s all-time greatest players. He hit for both power and average and was a solid outfielder. He is baseball’s all-time leader in runs batted in, extra-base hits, and total bases.

The Braves, Mr. Aaron’s team for 21 of his 23 major-league seasons, said he died “peacefully in his sleep.” He is the 10th Hall of Famer to die since the start of 2020, the third this year.

“Henry Louis Aaron wasn’t just our icon,” the Braves said in a statement. “But one across Major League Baseball and around the world.”

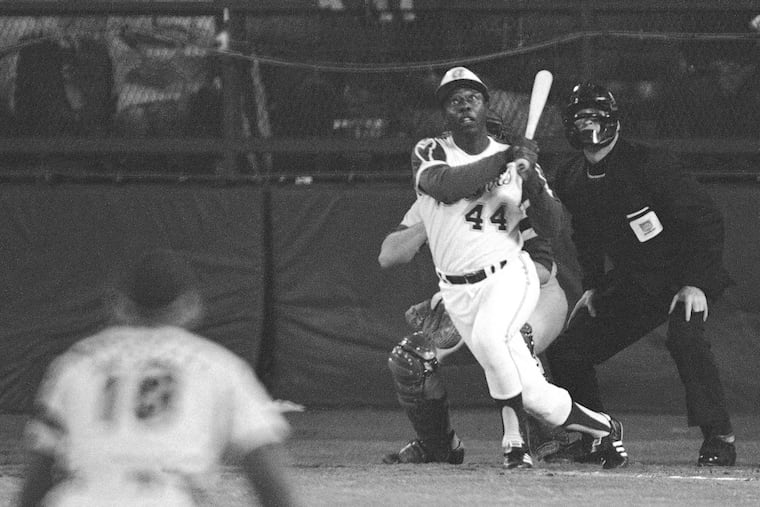

Mr. Aaron achieved icon status on April 8, 1974, when he hit his 715th career homer, passing Ruth’s mark. He grew up poor in Mobile, Ala., taught himself to hit with an unorthodox cross-handed swing, and blossomed into one of the game’s legendary figures.

Fans followed Mr. Aaron’s pursuit for more than two years leading up that night at Atlanta Stadium, watching him inch closer to becoming baseball’s home-run king. In 1973, he lamented all of the attention brought by the chase and the demands that consumed his life.

His pursuit of Ruth’s crown was marred by hate mail, death threats, and plots to kidnap his wife Billye and their children as racists could not fathom an African American holding one of the most celebrated records in sports.

Mr. Aaron kept the letters in his attic and would read them as reminders of the pain he felt. He said in 1992 that the chase “should have been the greatest experience of my life, but it was the worst experience of my life.”\

“I was just a man doing something that God had given me the power to do, and I was living like an outcast in my own country,” Mr. Aaron wrote in his autobiography, I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story. “I had nowhere to go except home and to the ballpark, home and to the ballpark. I was a prisoner in my own apartment. … That whole period, I lived like a guy in a fishbowl, swimming from side to side with nowhere to go, watching everybody watch me.”

President George W. Bush, who in 2002 presented Mr. Aaron with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, said “the former Home Run King wasn’t handed his throne” and “never let the hatred consume him.” President Barack Obama said Mr. Aaron was “one of the strongest people I’ve ever met.”

“Those letters changed Hank, but they didn’t stop him,” Obama said of the hate mail Aaron received. “After breaking the home run record, he became one of the first Black Americans to hold a senior management position in Major League Baseball. And for the rest of his life, never missed an opportunity to lead -- including earlier this month, when Hank and Billye joined civil rights leaders and got COVID vaccines.”

Mr. Aaron signed with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues for a $200 monthly contract when he was 18. He played 26 games for the Clowns, helped them win the 1952 Negro League World Series, and was signed by the Braves, who then played in Boston. Mr. Aaron reached the major leagues in 1954, just seven years after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier.

He appeared in 25 All-Star Games (including two each year in 1959-62), was a three-time Gold Glove winner, and a two-time batting champion. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, his first year of eligibility. Mr. Aaron’s walk-off homer clinched the 1957 National League pennant for the then-Milwaukee Braves, who went on to beat the New York Yankees in a seven-game World Series. He was named the NL MVP that season. He also helped the Braves reach the 1958 World Series, which the Yankees won in seven games. He retired after the 1976 season, his second with the Milwaukee Brewers after the Braves tried to move him from the field to the front office.

“Hank Aaron, thank you for everything you ever taught us, for being a trailblazer through adversity and setting an example for all of us African American ballplayers who came after you,” said Bonds, who is baseball’s all-time leader in home runs with 762. “Being able to grow up and have the idols and role models I did, helped shape me for a future I could have never dreamed of. Hank’s passing will be felt by all of us who love the game and his impact will forever be cemented in my heart.”

Mr. Aaron hit 76 of his home runs against the Phillies, who said Mr. Aaron’s “legacy is that of a gentleman who impeccably represented the game of baseball.” Mr. Aaron’s 700th homer came against the Phillies in Atlanta, off Ken Brett.

“He was one of my heroes as a kid, and will always be an icon of the baby boomer generation,” Phillies great and fellow Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt told the Associated Press. “In fact, if you weigh all the elements involved and compare the game fairly, his career will never be topped.”

Mr. Aaron’s record homer came on national TV. As Mr. Aaron rounded second base, he was met by two white teens who stormed the field. They startled Mr. Aaron after all those months of receiving hate mail, but they simply gave him a pat on the back before running away and being arrested. It became an iconic image as Mr. Aaron’s stressful home-run chase crossed the finish line.

“What a marvelous moment for the country and the world,” Vin Scully said on the TV broadcast. “A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking the record of an all-time baseball idol.”