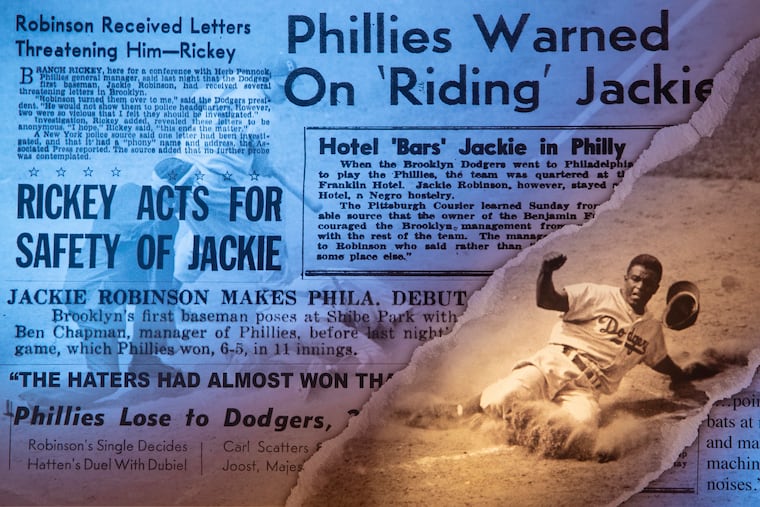

Death threats, a boycott warning and an awkward photo op: Remembering Jackie Robinson’s Philly debut 75 years ago

On May 9, 1947, Jackie Robinson played a major-league game outside of New York for the first time. And it included an experience he called "one of the most difficult things I had to make myself do.”

They stood together, side by side, in front of the home dugout and posed for the cameras. Jackie Robinson, left hand on his hip, cradled in his right hand the barrel of a bat that Phillies manager Ben Chapman gripped by the handle. In one frame, Robinson and Chapman smiled at one another. In the next, they gazed straight ahead.

It almost looked natural.

Seventy-five years later, the photo endures to mark an occasion, if little else. Robinson, the first African American player in Major League Baseball, was poised to play his first game in a city other than New York for the Brooklyn Dodgers; Chapman’s Phillies were the host. As historic moments go, it didn’t get more significant. A photo before a night game at Shibe Park seemed wholly appropriate, the perfect commemoration to send directly to Cooperstown.

» READ MORE: Jackie Robinson's legacy: 'He changed a country' and is still relevant 75 years later

If only it had been so simple, so innocent. If only the day — May 9, 1947, as hectic as any 24 hours in the integration of baseball — had gone so smoothly. If only ...

“I have to admit,” Robinson wrote in his 1972 autobiography, “that having my picture taken with this man [Chapman] was one of the most difficult things I had to make myself do.”

It was also right in line with the chaos of the day. Upon arriving in Philadelphia that morning, the Dodgers’ longtime team hotel denied them service, at least with Robinson among them. The Dodgers also went public with threatening letters that Robinson received in the mail, turning them over to the New York City police.

Oh, and the MLB commissioner’s office had to quell reports of the Cardinals’ threat of a players’ strike if the Dodgers brought Robinson to St. Louis for a series later in the season.

So, no, a Robinson-Chapman photo op didn’t seem at the time like such a big deal.

“I’ve been a pretty busy fellow the past week,” Robinson wrote in the May 17, 1947, edition of the Pittsburgh Courier, the nation’s leading Black weekly newspaper. “Between trying to play big league baseball and answering all kinds of questions about alleged strikes and threatening letters, I haven’t had much time to do anything else.”

Including, it seemed, share details of the way he had been treated by the Phillies — Chapman, in particular — a few weeks earlier in Brooklyn.

When it comes to Robinson’s rookie season, it can be difficult to distinguish between fact and myth. Robinson died in 1972, Chapman in 1993. None of the Phillies or Dodgers players who were there in May 1947 are living. Some accounts of the events don’t mesh with others.

» READ MORE: Dick Allen, the Phillies' first Black star, didn't let the boos and racism stop him from becoming an icon

A fuller picture of Robinson’s interaction with the Phillies in 1947 came to light decades later. In his autobiography, Robinson recalled Chapman and several players spewing hateful insults such as, “Hey, n—, why don’t you go back to the cotton fields where you belong?” He wrote that the episode “brought me nearer to cracking up than I ever had been.” The scene was portrayed vividly in “42,” the 2013 biopic about Robinson.

But in the aftermath of the April 22-24 series at Ebbets Field, there was little mention in the mainstream press of the Phillies’ behavior. Robinson was loath to say much after pledging to Dodgers president Branch Rickey that he wouldn’t protest when opposing players and fans attempted to bait him with racist taunts.

Over the next few weeks, some details trickled out. The Pittsburgh Courier reported that Chapman had “led his bench in a vile verbal attack” on Robinson. Chapman didn’t deny it, though he mostly dismissed it as “bench-jockeying.” He said the Phillies routinely hurled ethnic insults at their Italian, Polish, and Jewish opponents in an attempt to shift their focus.

Still, once word reached the league office — the New York Daily News reported that several fans complained that the Phillies “had engaged in unpleasant remarks” aimed at Robinson — commissioner Happy Chandler warned through a spokesman on the eve of the Dodgers’ road trip that such slurs were “contrary to the concepts of big league baseball and Americanism” and wouldn’t be tolerated.

And it was amid that backdrop that Robinson stepped off a train with his teammates on an unseasonably cold Friday morning in Philadelphia on May 9, 1947.

‘Not ready’ for Robinson

Less than a week earlier, Phillies general manager Herb Pennock phoned Rickey with a warning.

“You just can’t bring the n— here with the rest of your team, Branch,” Pennock said, according to a 1976 New York Times retelling by former Dodgers traveling secretary Harold Parrott, who was asked by Rickey to listen in on the call. “We’re just not ready for that sort of thing yet. We won’t be able to take the field against your Brooklyn team if that Robinson boy is in uniform.”

» READ MORE: John Irvin Kennedy dreamed of being the Phillies' Jackie Robinson. He never got the chance.

It was unclear to Parrott if Pennock was speaking for himself, Chapman, Phillies players, or the city. It also didn’t matter. Rickey told Pennock that the Dodgers would happily accept victories by forfeit.

When the Dodgers got to town, they took a bus from 30th Street Station to the Benjamin Franklin Hotel, their usual lodging on Chestnut Street between 8th and 9th streets. There are varying accounts of what happened next.

Parrott wrote in 1976 that the hotel manager informed him there were no rooms available and wouldn’t be in the future “while you have any [n—] with you,” even though the Dodgers provided their rooming list — including Robinson — weeks in advance. Parrott claimed to have called the Phillies for recommendations but got no answer from Pennock or owner Bob Carpenter before booking the Dodgers in the Warwick Hotel in Rittenhouse Square. The Warwick’s website confirms that the Dodgers did, in fact, stay there in 1947.

But the Pittsburgh Courier, citing an “unimpeachable source,” reported in its May 17, 1947 edition that Robinson stayed at the Attucks Hotel on 15th Street while the rest of the Dodgers were given rooms at the Benjamin Franklin Hotel.

Regardless, amid the Philadelphia hotel incident, reports out of New York were sobering.

The Dodgers turned over to the police at least two letters received by Robinson, the contents of which were described by the New York Daily News as “get out of baseball — or else!” New York City Police commissioner Arthur Wallender launched an investigation. The newspaper reported that the Dodgers also sought protection for Robinson, who had been receiving a two-man police escort out of Ebbets Field after every game.

Robinson downplayed the police presence. In his column for the Pittsburgh Courier, Robinson wrote: “The cops are just to keep the autograph hounds from mobbing me.” He dismissed the death threats as the work of “scatter-brained people who just want something to yelp about.”

But Robinson had tried to defuse the Phillies’ taunting, too, writing in the Courier that “Chapman impressed me as a nice fellow and I don’t think he really meant the things he was shouting at me.” It wasn’t until many years later that Robinson let loose. He said in his autobiography that the Phillies “brought me nearer to cracking up than I ever had been.”

‘Jackie has been accepted’

Through it all, Robinson still had a baseball game to play that night — and it was unlike any in his three-week major-league career.

The Dodgers played 13 of their first 15 games in Brooklyn, with the two road games coming at the Polo Grounds, the Manhattan home of the crosstown New York Giants. What sort of reception would he get outside New York?

Buzzie Bavasi, one of Rickey’s top deputies, said in author Jonathan Eig’s 2007 biography of Robinson that he suspected Rickey leaked news of the threatening letters on May 9 to engender public support for Robinson. Rickey, who died in 1965, never admitted to such motives.

Robinson’s arrival for a four-game weekend series at Shibe Park represented a boon for the Phillies. They hadn’t had a winning season since 1932 and were in the midst of a stretch of 31 losing seasons in 32 years. But they drew 40,952 fans for a Sunday doubleheader with the Dodgers, then a record crowd for a baseball game in Philadelphia. Even on that Friday night, in temperatures that “shivered around the freezing point,” according to the Daily News’ account, the Phillies reported a crowd of 22,680.

Chapman, likely at the urging of the commissioner’s office, issued a statement to the Associated Press before Friday night’s game. Responding to reports of abusive language directed at Robinson in Brooklyn, Chapman said, “Jackie has been accepted in baseball, and we of the Philadelphia organization have no objection to his playing, and wish him all the luck we can. Baseball is an American game, and there are no nationalities, creeds nor races involved. Jackie Robinson is an American.”

» READ MORE: Remembering Jackie Robinson in town where it started

Cue the flashbulbs.

It’s unclear whether Chapman initiated the photo op or was directed to do it by Rickey or Chandler, or both. But it was fair to question Chapman’s sincerity. And Phillies pitcher Freddy Schmidt told Eig that he overheard Chapman tell Robinson, “Jackie, you know, you’re a good player, but you’re still a n— to me.”

If Robinson heard it, he didn’t react.

Robinson batted second and played first base in that first game, a 6-5 Phillies victory in 11 innings. He doubled on a line drive to center field and scored in the fourth inning, then singled and scored in the Dodgers’ four-run eighth. According to the story in the next day’s Inquirer, Robinson “played brilliantly.”

Perhaps it was a turning point in what became a Rookie of the Year season. Robinson came to town in a 5-for-36 slump. But if he needed affirmation of the Dodgers’ belief in him, he got it after that first game in Philadelphia. Rickey sold Howie Schultz to the Phillies for $50,000, leaving Robinson as the only first baseman on the Dodgers’ roster.

The Dodgers lost three of four games to the Phillies, but Robinson had hits in each of them. By most accounts, the Phillies’ taunts were milder, although Chapman never made a public apology.

Sixty-nine years later, in 2016, the city said it was sorry for him.

Philadelphia councilwoman Helen Gym introduced a resolution to apologize “for the racism [Robinson] faced as a player while visiting” the city. It passed unanimously and was sent to Robinson’s widow, Rachel.