One terrible season derailed this former Phillie’s pitching career. It didn’t derail his life.

When players have historically bad seasons on historically bad teams, they often see their careers end. But Kyle Abbott has tried not to dwell on the “What if?”

In 1992, toward the end of baseball’s seat-of-the-pants era, when analytics and biomechanics hadn’t yet earned a spot in the dugout, Phillies starter Kyle Abbott was 0-11 and needed help.

“They’d just say, 'Go out there and do it,’ ” Abbott, who wound up 1-14 that year for the last-place Phillies, recalled recently.

Perhaps the most common advice offered the troubled young left-hander was a traditional baseball remedy that, to the detriment of his clubhouse standing, he rejected.

“I was maybe the only Christian guy in that clubhouse and I’m proud I never cheated on my wife in my baseball career," said Abbott, 51 and living in Texas. "So when I was unwilling to do that, they were like, 'Well, I guess he really doesn’t care about his career.’ ”

When the 2019 baseball season starts next month, 750 big-league players, each in his own way, will begin compiling statistics. A few may make history, though not always for the reasons they’d hoped. Last year, for example, Baltimore’s Chris Davis hit .168, the lowest average ever for a batting title-qualified player.

Some who fail as memorably as Davis or Abbott quit or get released. Others seek a change of scenery, a mechanical alteration, a new training regimen. A few bounce back. But most, burdened by the mental and physical scars of their seasons from hell, simply disappear.

Abbott, whose disposition was as sunny as his Southern California roots, is a fascinating example of a ballplayer who survived one of those sunless seasons. And if he hasn’t prospered in its wake, he certainly hasn’t been defeated.

Like most, he’ll always wonder how it happened, how a lifetime’s uphill journey so swiftly derailed. But, through interests as varied as whiskey and theology, he still seeks the success pitching once promised.

“My friends call me the 'Onion,’ ” he said during a recent telephone interview. “They say the more they talk to me, the more the layers peel away and they see all these other weird things I’m into. … It’s like I’m 51 and still haven’t decided what I’m going to do when I grow up.”

For those who remember the 1992 Phils — the “worst” in the worst-to-first story of their ’93 successors — Abbott threatened the team record for consecutive losses at the start of a season.

After five games as an Angel the previous season, he arrived here — along with Ruben Amaro Jr. — in a 1992 trade for Von Hayes. He earned a rotation spot that spring and made his first start on April 10, a 3-2 loss to Pittsburgh.

Abbott, 24, was 0-11 before getting his first win on July 18. His numbers were among the worst in club history — 1-14, a 5.20 ERA, a 1.446 WHIP, a WAR of minus-1.3.

“It was a snake-bit season,” he said. “It didn’t matter if it was me making a bad pitch at a critical time, or pitching a great game and getting beat, 1-0.”

Though it was 27 years ago, he still looks back in search of a reason. One possibility came on April 30, the night Abbott — 0-4 with a 5.76 ERA – got “rioted out” of a start in Los Angeles by the Rodney King disturbances.

“I got bumped into pitching against guys like Greg Maddux, Dennis Martinez. And there wasn’t much offense. I’d get to the sixth or seventh inning and start putting pressure on myself. What I needed to do was stay in control of myself. But it’s easy for a young pitcher to forget that.”

After Abbott’s year of unprecedented failure ended, he vowed it wouldn’t happen again.

Working out in a Marlton gym in the offseason, Abbott gained 30 pounds -- “without steroids” -- and hired sports psychologist Ken Ravizza. But he hurt his elbow in spring training and developed a second injury when he came back too soon. He spent the pennant-winning ’93 season at Scranton, broke down in ’94 after signing to play in Japan, pitched 28 innings with the ’95 Phillies, four with the ’96 Angels, and was done.

“By then the business had beaten the love of the game out of me,” he said. “I hated baseball.”

“By then the business had beaten the love of the game out of me. I hated baseball.”

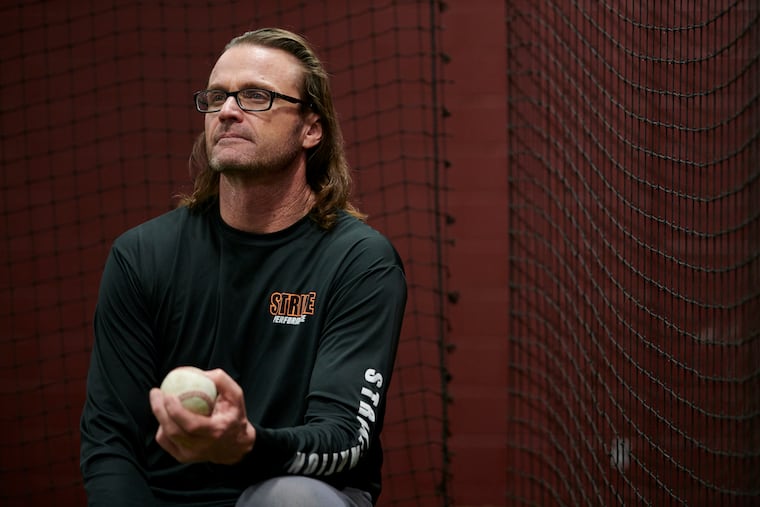

Despite that, he didn’t abandon the sport. Settling in Texas for tax reasons, he began tutoring young players. A few years ago, he co-founded a Dallas-Fort Worth-area coaching center with two other ex-big-leaguers – Daniel Ortmeier and Luke Carlin. Among the athletes Strike Performance has counseled are Red Sox reliever Colten Brewer and Nationals pitcher Austen Williams.

“It’s been a blast,” Abbott said.

He and his ex-wife (their 10-year divorce process ended in 2018) never had children, but Abbott, who lives with his girlfriend in Krum, Texas, has developed a paternal relationship with some students.

“I’m able to pour more of myself into those kids,” he said. “I’ve coached their travel-ball teams, been invited to their weddings, graduations.”

But baseball alone wasn’t enough for Abbott, who also excelled at water polo while growing up in a San Diego suburb, so he veered into areas normally off-limits for ex-ballplayers.

An outspoken Christian on a Phillies team that, many would argue, was badly in need of salvation, he earned a master’s in theology. For several years he headed the Texas Rangers’ baseball chapel, but after his divorce process began, he backed away from active ministry.

“There weren’t any hard feelings, but you become a pariah. It’s that Christian culture where you’ve got to put on an image where you’re perfect,” he said. “If you’re not it’s, 'We don’t want you in the ministry.’ ”

Abbott had traveled the globe preaching baseball and the Bible. In Italy, France, and elsewhere he took cooking courses, immersed himself in the cultures, tried to live outside the box baseball had made for him.

During his one unproductive season in Japan, he learned the language with an eye toward becoming a cultural liaison for the Japan League players then starting to come to the U.S.

“I’d travel to the winter meetings to pitch that idea,” he said. “When the Twins signed [Tsuyoshi] Nishioka, I warned them he was going to struggle with the adjustment. They didn’t listen and he failed.”

Eventually, the trips to Japan and the winter meetings grew too expensive for someone supporting himself with a few lessons and what was left of his baseball money. Abbott, who got a $190,000 signing bonus as the Angels’ first-round pick in 1989, earned $109,000 with the ’92 Phils and got a “much more lucrative contract” with Kintetsu, lives well but frugally.

“When I was a first-rounder for the Angels, my dad told me to make just enough money in the game so you can do what you want,” he said. “I’ve never been financially independent, but I’ve made enough that I didn’t have to get a 9-to-5.”

His own physical breakdowns inspired a fascination with biomechanics.

“Working on my master’s now, I realize everything I learned while I was playing is wrong,” Abbott said. “From recovery to nutrition, it’s all different. When I played, hitters weren’t concerned with launch planes. They just wanted to see the ball well. Same with pitching.”

Abbott is taking online courses in a master’s program, soon will be certified as a performance-enhancement specialist, and hopes to get his Ph.D in biomechanics. Ideally, he’ll consult teams whose injured pitchers need not just physical but mental rehabilitation.

“My experience in ’92 helps me a lot with that,” he said.

And through it all, this player who was a model citizen in raucous clubhouses has somehow found time to study and savor quality whiskey.

“Whiskey,” he explained, “is just … good.”

Get insights on the Phillies delivered straight to your inbox with Extra Innings, our newsletter for Phillies fans by Matt Breen, Bob Brookover and Scott Lauber. Click here to sign up.