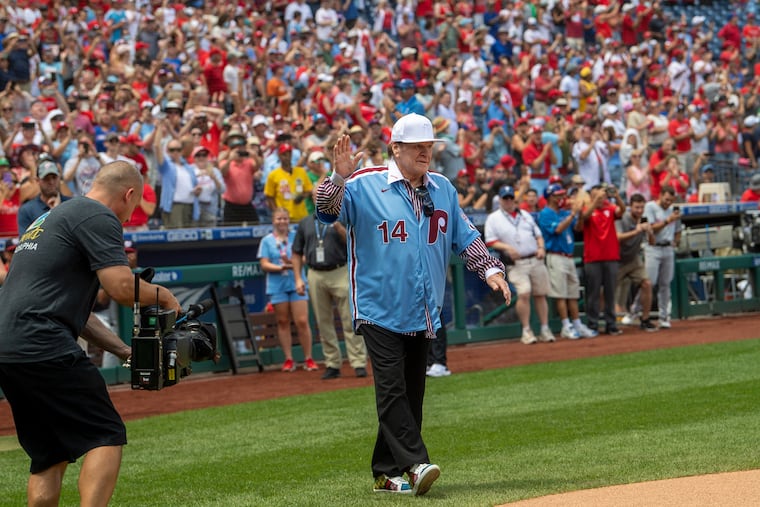

The day Pete Rose proved he does not belong in baseball. Or anywhere in public.

Pete Rose showed the same lack of class in his appearance with the 1980 Phillies that he has always shown, and it's what the Phillies deserved for inviting him.

If there is one compliment that you can give Pete Rose without feeling the need to rinse your soul out with Listerine, it is that he has consistently kept the world informed about how unattractive a human being he really is. There are plenty of celebrities who act one way in public and another in private. Rose? He’s never paid much attention to his surroundings. From his infamous on-field push of umpire Dave Pallone to his long list of off-the-field transgressions (illegal gambling, tax evasion, etc.), Rose has always made it perfectly clear to anybody with an ethical pulse that he was, is, and will continue to be a bona fide and unapologetic jerk.

» READ MORE: The rise and fall of Pete Rose: Gambling, statutory rape allegations and ban from baseball

All of this brings us to an important philosophical question that the Phillies should be asking themselves after Rose spent his Sunday embarrassing himself and everybody in the organization who thought it was a good idea to include him in their celebration of the 1980 world championship team. When a jerk acts like a jerk, is it entirely his fault? Or does the blame fall partly on those who thought he might act another way?

Maybe that sounds like a leading question, but that’s the point. There’s only one direction things could have gone. The idea that Rose’s appearance in Philadelphia would be some sort of celebratory triumph completely ignored the notion that his absence might have been due in part to the fact that he was not someone who was pleasant to have around. By the end of Sunday’s proceedings, that inconvenient truth was no longer possible to ignore.

» READ MORE: The Phillies didn’t have to bring back Pete Rose. But they could make things easier on themselves. | Mike Sielski

Rose began his day by condescendingly referring to a female Inquirer reporter as “babe” while dismissing her question about his admitted relationship with a girl who decades later offered a sworn statement that she had been under the age of consent when the relationship began before she turned 16. Later, he responded to a similar query from a different reporter by asking, “Who cares what happened 50 years ago?” It is unclear if anybody thought to remind him that he was attending a commemoration for something that happened 42 years ago. Rose later attempted to make amends with the first reporter by offering to sign 1,000 baseballs for her. He also found time to drop a couple of profanities on live television during the Phillies’ broadcast of their 13-1 win over the Nationals.

In short, Rose came across as exactly the sort of person who would do all of the things that he has been accused of over the years, because he came across as a person who operates with a fundamental belief that he exists at the top of the food chain and, thus, the rules do not apply to him. His purposeful use of the word “babe” to diminish a female Inquirer reporter who dared to question him carries more than a whiff of the same disturbing power dynamic that former MLB investigator John Dowd accused him of exploiting during the 2015 radio interview that led to the civil suit that resulted in Jane Doe’s statement. His insistence that “nobody cares what happened” 50 years ago suggests an ingrained belief that “what happened” happened only to him, and that the girl with whom he was involved does not even rise to the level of somebody who might care about what happened.

Keep in mind, these are just the most concerning symptoms of Rose’s character. Even before Dowd’s comments and Jane Doe’s testimony during the ensuing civil suit, Rose had spent the majority of his post-playing career providing evidence that he was a man whose only redeeming quality was his ability to handle a baseball bat. A little more than a year before the August day in 1989 when Bart Giamatti announced Rose’s lifetime ban for betting on baseball, Rose had pushed an umpire while managing the Reds and received a month-long suspension that at the time was the longest ever for an on-field incident. A year after the ban, Rose was sentenced to five months in prison for tax evasion stemming from his failure to report income stemming from memorabilia sales. Through it all, Rose adapted a public posture that painted himself as the victim, a man who does not need to apologize.

» READ MORE: Rose on critics of his appearance with the 1980 Phillies team: ‘It was 55 years ago, babe.’

Truth is, the gambling ban might be the best thing that ever happened to Rose. Instead of forcing him into the anonymity of retirement as just another among hundreds of Hall of Famers, it allowed him to market himself as a pariah and turn his exclusion into a lucrative cottage industry. More significantly, it masked the increasingly obvious reality that his banishment from baseball was a product of something much deeper and darker than a gambling habit.

At some point, though, the blame needs to fall on the people who cannot see Rose for anything more than his on-field production. Five years after the Phillies were forced to scuttle Rose’s Wall of Fame induction following the Jane Doe revelations, they attempted to reconcile their invitation to him by stating that he was only being honored as part of a team. But how many times must a person prove that he does not deserve the benefit of the doubt before the focus should shift toward those who continue to provide it to him? This goes not only for principal owner John Middleton and the Phillies organization, but the members of that 1980 team who supposedly encouraged Rose’s inclusion.

Rose accomplished plenty on the field, and the Phillies are correct that you cannot write that out of the history books. But the only thing he accomplished on Sunday was proving that he does not belong in baseball, and probably not in public. You can only hope that it proves to be his greatest accomplishment yet.