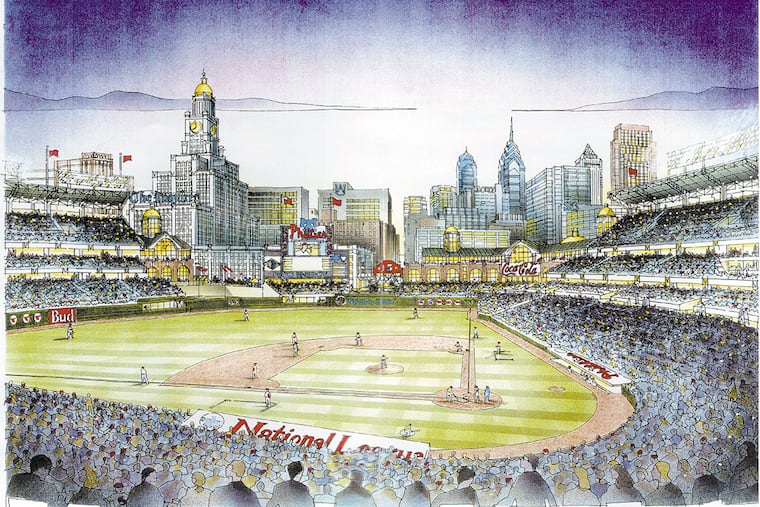

What if the Phillies ballpark had been built in Center City?

Aside from the ballpark's current location, there were three other serious contenders.

In the spring of 1992, the city of Baltimore unveiled the latest addition to its downtown revitalization project, and incidentally, started a revolution.

Oriole Park at Camden Yards, with its downtown location, nostalgic ambiance and charming 19th century warehouse backdrop, kicked off an ultra-urban, retro-themed stadium boom. Nine retro-modern parks were built in the decade following Camden Yards’ arrival, and another nine — mostly sticking to principles established by the Baltimore design — would open before the end of 2010.

Bill Giles and David Montgomery, who were then heading the Phillies, visited Baltimore shortly after the grand unveiling and, so the story goes, got that new-ballpark-smell lodged in their brains. The two began concocting plans to flee the dilapidated Veterans Stadium and build their own iconic playground.

It was the ’90s, and the Vet was one of the worst — if not the worst — stadium in two major professional sports leagues. By the middle of the decade, both the Eagles and the Phillies were itching to ditch the concrete bowl in favor of new and separate spaces.

The Eagles preferred to stay close to their longtime home, looking at the South Philadelphia Sports Complex near the Spectrum and the Wells Fargo Center (then First Union Center), which was built in 1996.

The Phillies, on the other hand, favored a downtown location with a view and amenities. But that didn't come to pass, and in the end, the Phillies abandoned their cross-town dreams and settled down with the rest of the family in South Philly.

What drove the decision? The usual suspects: money, infrastructure, politics.

Twenty years after the team kicked their pursuit of a downtown location into high-gear, we take a look at what could have been. Aside from the ballpark's current location, there were three other serious contenders:

Broad and Spring Garden

Giles and Montgomery envisioned a baseball diamond closer to Center City’s skyscraper-reflected sunlight and buzz of young-professional exuberance.

The early favorite: the southwest corner of Broad and Spring Garden, next to the old Inquirer building and midway between Temple University and Center City.

Mike Rosen, head of the now-defunct Philadelphia Virtual Reality Center that worked with the Phils' architecture firm Ewing Cole on location scouting, called the site an "economic driver."

"You would have re-energized that part of the city, similar to Baltimore," he said. "It would have activated that whole corner of Spring Garden."

To make it work, streets would have been closed and traffic rerouted. But, Rosen said, the positives outweighed the negatives.

“It would have created, right there in the heart of the city, its own vitality,” he added. “When people got out of the gate they would head into the neighborhoods and fill the restaurants as opposed to just hopping in your car and leaving.”

Gary Jastrzab, executive director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, said he wasn't involved in the project at the time, but he believes most planners were pulling for this location. And the commission ultimately voted for it.

"The sense was that it was close to Center City in a reasonable walking distance, well served by public transit, there are a lot of parking facilities in and around the area that would accommodate the parking, and so on," he said.

Rosen said the Broad and Spring Garden site would have done “something extra” for the city, unlike Citizens Bank Park, “which is just another building amongst a bunch of other sports buildings.”

An executive with the Phillies who participated in the search for a ballpark location countered that the Sports Complex has its own list of advantages. It’s easily accessible to area highways and positioned to serve the whole tri-state area. It’s not far from the airport, there’s a subway station nearby, and it has a lot of parking.

The team also says a majority of fans and season ticket holders had opposed the downtown ballpark, citing congestion, parking prices and hassle. And it would have cost the Phillies more money, adding parking garages, relocating utilities, and fitting a major modern facility onto Philly's 300-year-old infrastructure.

Politics also intervened.

State Sen. Vincent Fumo — who in 2009 was convicted of 137 counts of federal fraud and ultimately served 61 months in prison — reportedly vetoed the site.

Fumo represented the district where the park would have been built. But he opposed the site, Rosen said, because "his house was four blocks down the road."

According to news reports at the time, Fumo gave other reasons: The potential for traffic and parking problems in the area, and community opposition.

31st and Walnut

Jastrzab didn’t join the City Planning Commission until 2001. But looking back at the potential sites, he said, “I would have liked to see the ballpark built on what was then known as the postal lands, where Penn has developed its Penn Park.”

“If you ever walk through that area, it has a magnificent view of Center City skyline,” Jastrzab said, “and since the batter is supposed to be facing toward the northeast, it would have been just a great location for a ballpark.”

The location — at 31st and Walnut streets in University City just south of the main Post Office and adjacent to the Schuylkill — not only offered cinematic views, but also sat next door to 30th Street Station and subway lines.

The Phillies executive, who requested anonymity because he was discussing confidential real estate negotiations, said the West Philadelphia site was favored by developer Dan Keating. It had a lot of promise, but also a lot of drawbacks, such as congestion and parking issues, the official said.

Jastrzab said he wasn't sure what specifically killed that proposal, but he recalls a lot of pushback from surrounding communities and from the University of Pennsylvania, which "had another use in mind," he said.

It would eventually become home to Penn Park, including two athletic fields and a multi-purpose stadium.

The Phillies executive said both concepts were provocative.

"University City was very cool, but Broad and Spring Garden was the leading contender for a while," he said.

13th and Vine

The 13th and Vine streets pitch was a last-ditch effort by the new mayor, John Street, to salvage a Center City ballpark location. But he ran into a tremendous amount of opposition.

"The Chinatown community had really felt that their particular neighborhood had been seriously impacted by a whole bunch of different municipal projects over the years," Jastrzab said.

Those projects included construction of the Vine Street Expressway, the Convention Center, and even Independence Mall, which limited the neighborhood to the east side.

"If you have ever traveled down Vine Street from I-95 heading toward the Schuylkill Expressway, that's an area where Vine Street goes from above ground to below ground, you can just imagine what a ballpark sitting there as you descend below ground might look like. I think it could have been really spectacular," Jastrzab said. But in practical and engineering terms, he said, the site was fairly constrained.

There were also the typical concerns about traffic, parking, the effect on businesses and access to public transit.

The architect Mike Rosen said flatly: "It just didn't work there. You couldn't get to it."

The Phillies executive said the mayor's proposal was "well intentioned," but was cost-prohibitive with all of the work that had to be done.

Bonus round

There were other, less-popular ideas bandied about in the late 90s and early 2000s, including sites in Port Richmond and Kensington, over the train yard north of 30th Street Station, FDR Park, and South Broad Street at Washington Avenue.

Some residents swooned over the success of the San Francisco Giants' harbor-side AT&T Park, and proposed a similar stadium on the waterfront at Delaware Avenue and Spring Garden.

Rich Villa, an architect and partner at Ambit, drew up some sketches.

His designs, while they were not commissioned by the Phillies and were developed after the Sports Complex site was chosen, do offer an idea of how a stadium would have fit on the waterfront.

Fellow Ambit architect and partner Jason Birl said the stadium would have done what many current projects along the waterfront are still hoping to accomplish: "Activate the river."

Ultimately, it was not where the Phillies wanted to set up shop.

A fifth option was not opposed by any local civic groups, but actually championed by them: the old Schmidt brewery on Girard Avenue in Northern Liberties, which eventually became The Piazza at Schmidt's.

The civic group, comprising of local business people and residents, even came up with a catchy name for the new stadium: Liberty Yards.

Even though the residents thought the stadium would have benefited the area, as with the other sites, the Phillies just weren't interested.

In the end

All stadium proposals face major hurdles. But if the political will had been different, would a Center City ballpark have surmounted the other concerns — density, infrastructure, cost?

According to the Phillies executive, "I think so, yeah."

"If the neighborhood opposition was smaller, and the political support was stronger, then yeah I think that would have changed things."

Fast forward 20 years, and this is what we got: a quirky brick box designed for a dense urban enclave, built on a full city block and set among a sea of parking spaces. Fans got nice sight lines, wide concourses, and easy access to the major highways.

“At the end of the day, I think the right decision was made to build it down here,” the Phillies executive said.

Gary Jastrzab tended to agree.

“A downtown ballpark would have really been a magnificent thing to have,” he said. “Having all of the stadiums down there — football, baseball, an indoor arena — that’s not so bad either.”