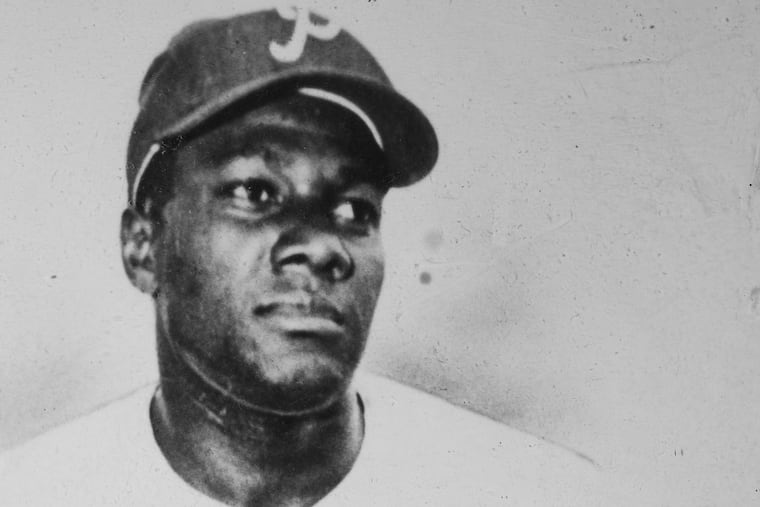

Phillies to honor John Irvin Kennedy, their first African American player

Sixty-five years after his debut, the Phillies will pay tribute to Kennedy with an on-field ceremony on June 29

ARLINGTON, Texas — Tazena Kennedy never thought she’d see the day. Her father, shortstop John Irvin Kennedy, played only five games and had just two at-bats for the Phillies in 1957, but he was still the first African American player to ever wear that uniform. He paved the way for Dick Allen, Jimmy Rollins and Ryan Howard to wear that uniform, too. She felt he deserved to be recognized.

But as the years passed, she became less optimistic. Kennedy, a native of Jacksonville, Fla., died in 1998. After the Phillies released him in 1960, he never heard from the organization again. Neither did his family until April 23 when Tazena got a call from Rob Holiday, the Phillies’ director of amateur scouting administration.

» READ MORE: John Irvin Kennedy dreamed of being the Phillies' Jackie Robinson. He never got the chance.

Sixty-five years after Kennedy’s debut, the Phillies will honor him with an on-field ceremony on June 29 at Citizens Bank Park before their game against the Atlanta Braves. The Phillies will also unveil a display to commemorate Kennedy on the stadium’s Hall of Fame level. Tazena will be in attendance along with her three daughters and her five grandchildren.

“It’s been a long time coming,” Tazena told The Inquirer. “I wish he was here to experience all of this, but I’m glad it’s happening. So that people will know that he’s a part of history. Even though it was short-lived, for whatever their reasoning was, he made it. For him to have been a Black player during that time, you had to be extraordinary, beyond extraordinary, to make it to the major leagues.”

With Kennedy’s arrival 10 years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, the Phillies became the last of the existing National League teams to integrate.

“I always hear about Jackie Robinson, Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and my father has kind of been overlooked,” Tazena said. “Now people will be able to see that he made a contribution. It just fills my heart with joy and gladness.”

Tazena was surprised when she heard from Holiday. She’d come to terms with the notion that her family would celebrate Kennedy’s contributions on their own. They would keep his legacy alive by sharing his story with anyone who would listen. Now, the Phillies are listening. It all feels a little bit surreal.

“I’m still kind of in shock,” she said. “I really didn’t expect it. He’s been gone for about 25 years. I don’t think it’ll feel real until we’re actually there, in Philadelphia, at the ballpark.”

» READ MORE: Dick Allen, the Phillies' first Black star, didn't let the boos and racism stop him from becoming an icon

Kennedy never understood why he was released, or why his big-league career was as brief as it was. In April 1957, he was coming off a strong spring training in which he’d batted over .300 and apparently won the starting shortstop job. But the Phillies traded for Chico Fernandez from the Brooklyn Dodgers a week-and-a-half before opening day. After showing what seemed to be a lot of promise, Kennedy never got an extended look. (Of the five games in which he appeared, three were as a pinch runner).

That question — why he didn’t get an extended look — lingered with him for the rest of his life. It was one that ultimately went unanswered. There is nothing the Phillies can do now to fix that. But celebrating Kennedy is an important step. It is an acknowledgment that those two at-bats and five games mattered. It is an acknowledgement that somebody had to be first, and that Kennedy was brave enough to do it.