Reggie Jackson calls return to Birmingham ‘not easy’ and shares the racial mistreatment he endured

The Hall of Famer gave an honest answer when asked how it felt to be back at Rickwood Field, describing some of the racism he faced as player.

Major League Baseball descended on Rickwood Field this week to honor and celebrate the Negro leagues and Willie Mays, who died Tuesday. But for one Hall of Famer, the trip to Birmingham, Ala., brought back painful memories during a time of racial segregation in America.

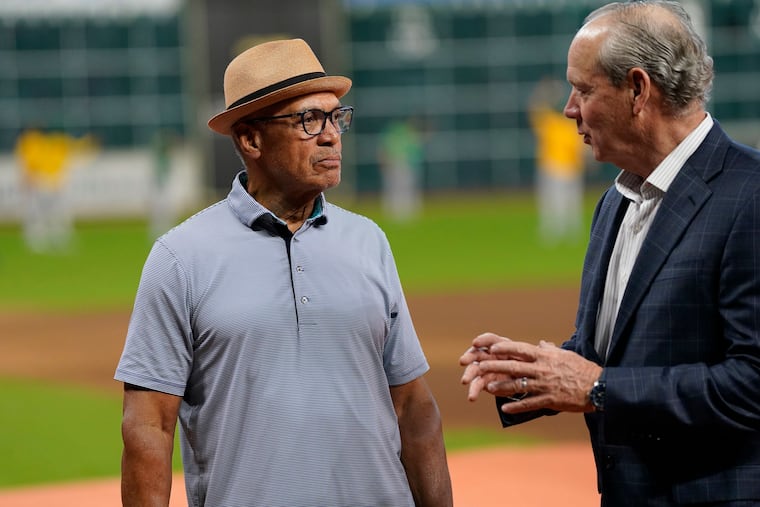

During Fox Sports’ pregame show that featured Kevin Burkhardt, Alex Rodriguez, David Ortiz, Derek Jeter, and Reggie Jackson, the crew dug into the significance of how players like Mays, Jackie Robinson, and Jackson paved the way for racial integration in baseball. Rodriguez asked Jackson, “How emotional is it to come back to a place that you played, with one of the greatest teams around?”

Jackson gave a nearly three-minute response, peeling back the layer of the racism and oppression he faced as a member of the Oakland Athletics’ minor-league club, the Birmingham A’s, led by manager John McNamara. A 21-year-old Jackson played 114 games with the club in 1967.

» READ MORE: Willie Mays was so much to so many. His legacy — and humanity — will still be celebrated.

“When people ask me a question like that, coming back here is not easy,” Jackson responded. “The racism when I played here, the difficulty of going through different places where we traveled … fortunately I had a manager and I had players on the team that helped me get through it, but I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.”

Jackson, 78, a 1964 graduate of Cheltenham High in Montgomery County, went on to describe how when he walked into restaurants, workers would “point at me and tell me that I can’t eat here.” Lodging was also difficult for Jackson and his team, as they weren’t allowed to stay at hotels because of his skin color. Even at a welcome home dinner at a country club, he said, employees pointed out Jackson and “called me the N-word.”

At one point, Jackson was sleeping on the couch at the apartment of teammate Joe Rudi and his wife, Sharon, for “three or four nights a week, for about a month and a half.” The Rudis received threats that the apartment complex would be burned down if Jackson continued staying there.

Jackson credits his manager, McNamara, for sticking up for him, saying that “if I couldn’t eat in a place, nobody would eat; we’d get food to travel.” He also pointed to his teammates Rollie Fingers, Dave Duncan, and Lee Meyers for their support, and said that without them, he “would have never made it. I was too physically violent … I would have gotten killed here [in Birmingham], because I would’ve beat someone’s [expletive].”

» READ MORE: Scott Bandura returns to Rickwood Field ‘grateful to be included’ in MLB’s Negro Leagues celebration

He played two seasons in the minors before spending the next 21 seasons in the major leagues, with the Athletics, Orioles, New York Yankees, and Angels. He led the American League in home runs four times, was the 1973 AL MVP, and finished his career with 563 home runs, which ranks 14th all-time. He was enshrined in the Hall of Fame in 1993.