Scott Bandura returns to Rickwood Field ‘grateful to be included’ in MLB’s Negro Leagues celebration

The minor leaguer grew up learning Black baseball history in South Philly — from his parents and on barnstorming trips with the Anderson Monarchs.

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — From front fender to muffler tail, the white, silver, and black 1947 Flxible Clipper bus could not help but awe as it sat outside historic Rickwood Field.

The passenger bus bore the name of the Birmingham Black Barons. Yet anyone who knows Steve Bandura would immediately suspect that the fingerprints all over the 1947 beauty belonged to him and his many teams affiliated with the Marian Anderson Recreation Center in South Philadelphia.

With a twinkle in his eye, Bandura, who works for the Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department, confirmed just that Wednesday. MLB wanted the bus on site so badly, it re-lettered the vehicle for this specific event.

» READ MORE: The night West Philly’s Arlington Henderson faced the legendary pitcher Satchel Paige

The sleek and shiny bus is usually very easily recognizable as the Marian Anderson Center’s transport. It has made many a trip ferrying the Anderson Monarchs teams (named after the Kansas City Monarchs). It has become a centerpiece in the Monarchs’ never-ending odyssey, as Bandura continues to find opportunities to show generation after generation of children the rich, but too often overlooked, history of African American baseball.

So the re-outfitted bus surprised no one from Philly with its presence here, in town for this singular week as baseball celebrates the Negro leagues, the Monarchs, Philadelphia Stars, and, of course, the Black Barons and their most famous player, Willie Mays.

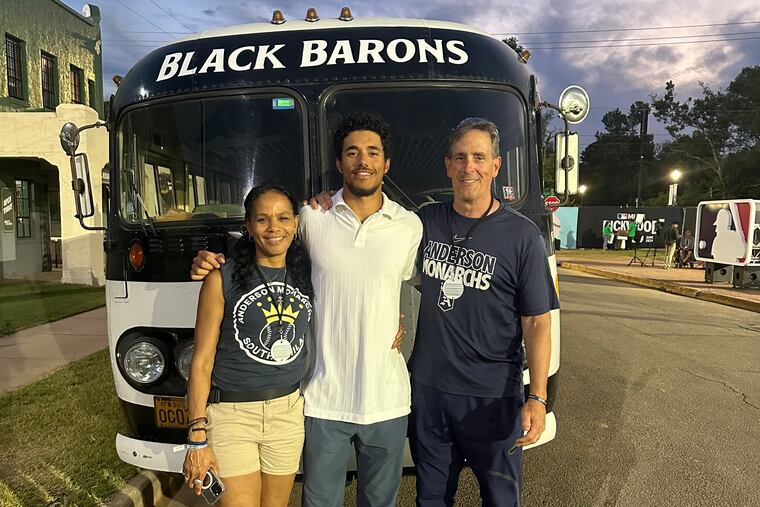

There was another very important reason Bandura and his wife Robin, a physical therapist, are in Birmingham. Their 22-year-old son, Scott, is in his first professional season in the minor leagues with the San Francisco Giants. The big-league team asked Scott Bandura and other minor league players with Black heritages to travel to Birmingham with the big-league club. The Giants and Cardinals wanted their potential future stars to experience the history made Thursday night when the teams played at Rickwood Field in the first-ever regular-season MLB game played at a Negro leagues ballpark.

» READ MORE: Scott Bandura is now a pro ballplayer, but he’s OK with being remembered as a Taney Dragon

“I am just grateful to be included,” said Scott, whose mother is Black and father is white. “They obviously took a bunch of us all the way out here, got us away from the field for a day. We could have been playing right now. They let us get away to experience this, and I am grateful.”

To Scott, who was the catcher on the 2014 Taney Dragons Little League World Series team that captured the attention of the nation, it was another experience of the sort he enjoyed often as a Monarch. He once benefited from being a part of his father’s initiatives, trips, and lessons that so richly colored his youth as an Anderson Monarch. For that reason, while MLB may have been new to Rickwood, it was not to Scott. For he and the travel-savvy Monarchs played at Rickwood in 2015.

“It hasn’t changed much at all,” he said as he stood on the field. He did notice the major-league-worthy temporary lights on cranes towering above the stands. “Yeah, I noticed those. And I guess the padded walls and the scoreboard are the only things that are different.”

» READ MORE: Willie Mays was so much to so many. His legacy — and humanity — will still be celebrated.

When the game began, Scott was in the stands, like his parents. Sharing these events with his mom and dad isn’t knew, but it never gets old, by the look of excitement on his face.

“I’m grateful for them because I got to grow up learning these things about baseball,” Scott said. “Now it’s baseball taking me to places I could never imagine, and now that I am back here and have that background, that knowledge, I can appreciate this stuff so much more.”

From the sound of it, the learning is as important as the opportunities to him. Scott absorbed his parents’ thirst for knowledge and completed his junior year at Princeton before being drafted in the seventh round by the Giants in 2023. He intends to return to Princeton in the offseason to finish a degree in economics. The Giants will pay for the final semester in the fall.

If Robin and Steve Bandura have their way, Scott won’t be the last beneficiary of the education offered at the center named for Anderson, the African American singing legend from South Philly. Nor will he be the last to know how to recite the history of Jackie and Willie, Hank and Frank almost before he learned to walk.

“He learned from an early age that what Steve has done with the Monarchs is bigger than us,” Robin said. “He’s taken that to heart.”

As for the bus, it is not a coincidence that it was made the same year Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, breaking the color barrier. Though it was brought to Birmingham on a flatbed truck, it’s done more than its fair share of long hauls.

“Out last trip covered 4,500 miles in 23 days,” Steve said.

Scott wasn’t yet born when his father used the same 1947 bus to take the Monarchs on their first national trek, to Kansas City and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, then back.

» READ MORE: Hayes: Willie Mays was the greatest baseball player ever, and there is no honest debate about it

On that inaugural trip, the Monarchs’ first stop was at Robinson’s grave in suburban New York. Scott smiles at the mention of such ventures, pointing out Robinson was never far from the baseball curriculum at Marian Anderson. So it is no surprise that Robinson is the Negro leagues player he would have most liked to meet.

“I have his ‘42′ tattooed on my wrist,” he said, a Giant’s giant salute to a Dodger.

“It’s amazing, and I think he understand the impact of Jackie Robinson more than most because we were always the only Black team in any of our leagues and tournaments,” Steve said. “Although Scott had his teammates, there was still that isolation and outsiders’ status in youth baseball.

“Like Jackie, their performance refuted a lot of preconceived notions their opponents had coming in. That whole team was filled with barrier breakers. They felt like they were blazing a trail for kids coming after them.”