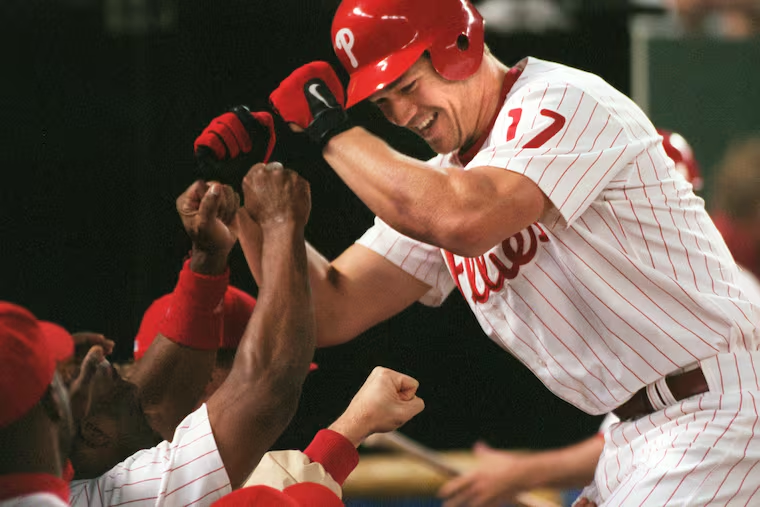

Scott Rolen is about to be a Hall of Famer, and he was never the bad guy with the Phillies

Many around here remember him as a guy who didn't like Philadelphia or its baseball fans. But in hindsight, he was right in his criticisms of the Phillies at the time.

Scott Rolen will be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame next weekend, and the occasion promises to reignite a series of debates around here that have the staying power of a syndicated sitcom. Does Rolen deserve enshrinement? Was he a great player? A very good player? An underrated player? An overrated player? And was he really the bad guy that so many fans and media, during his final few seasons with the Phillies, thought him to be?

That last question is the most interesting one, at least in these parts. A fair evaluation of Rolen’s career in the context of Major League Baseball history makes it pretty clear that he was a worthy candidate. Rolen played in the field in 2,023 major-league games, all of them at third base, which is the least-represented position in Cooperstown. There are just 17 third basemen in the Hall of Fame — not because the standard at that position is so high, but because so few full-time third basemen over the last three decades have been outstanding players — and Rolen’s combination of fielding excellence and offensive production allows him to vault that bar. He’s in, and he should be in.

The idea of Rolen being a Hall of Famer likely still rubs some Phillies fans raw. Like Eric Lindros, like Carson Wentz, like Ben Simmons, Rolen began his career in Philadelphia as a beacon of hope and left under a dark cloud. But anyone harboring animosity toward him for turning down a $140 million contract offer, coming into conflict with a couple of Phillies icons, and forcing the franchise to trade him in 2002 should have gotten over that anger long ago. If anything, the years since his departure — and the strides that the Phillies have made over that time — should cast his tenure in a better light.

“There’s a three-to-four-month period there where — I don’t know how you want to say it — there was a misunderstanding,” Rolen said Friday during a videoconference call when asked about the circumstances of his leaving the Phillies. “We weren’t on the same page necessarily. Unfortunately, it got a little public. I think we all wanted the same thing, and it didn’t come off that way necessarily.”

What Rolen wanted — what he told Phillies leadership and said publicly — was simple: Before he made any kind of long-term commitment to the team, he wanted ownership to commit to spending enough money on player salaries to put a competitive club on the field.

Rolen became the Phillies’ everyday third baseman late in the 1996 season and was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in July 2002. The Phillies had a losing record in six of those seven seasons, were in the midst of a 17-year stretch in which they finished above .500 twice, and were notorious for being a big-market team that behaved like a small-market one.

Granted, Veterans Stadium was still standing and Citizens Bank Park was coming, but Rolen was skeptical that a new ballpark would make much of a difference — not an unreasonable view for someone in his position to take. He was supposed to sign here and trust that the Phillies would cast aside all that history of futility?

“The question is, do you commit at that point two, three years down the road from a stadium?” he said Friday. “Do you commit your whole career, or do you see what free agency looks like? That was my decision at the time, and I understand that the Phillies needed to make a move. They couldn’t bank on that necessarily.”

Just as damaging to his perception among the team’s fans, Rolen drew the ire of two popular, old-school baseball men. Dallas Green, a senior adviser for the Phillies at the time, said in August 2001 that Rolen was “satisfied with being a so-so player. He’s not a great player. In his mind, he probably thinks he’s doing OK.”

Green’s upbraiding of Rolen was ridiculous — did he ever watch him play? — but he had momentum on his side. He delivered that criticism just two months after Rolen, while batting cleanup, had struggled during a three-game set against the Boston Red Sox and then-manager Larry Bowa reportedly had said: “If the number-four guy even makes contact in either Boston loss, we sweep the series. He’s killing us.”

Bowa has always maintained that he was misquoted, that he had said, “The middle of the lineup was killing us.” It was a distinction without any meaningful difference, and this was a young, allegedly entitled athlete against two heroes of the Phillies’ 1980 World Series team. This was a public-relations fight that Rolen was never going to win, especially given the antiquated manner in which the Phillies and those who followed them thought about and framed the problem. One writer who covered the team then put it this way: “This leaves the Phils with a choice: Do they build their team around Rolen? Or do they build it around Bowa?”

» READ MORE: Our top 10 Phillies draft picks of all time

The notion that any major-league franchise serious about winning would choose to build around its manager — any manager — and not its Gold Glove, .877-OPS, just-entering-his-prime third baseman is laughable now. It should have been then, and it only proved Rolen’s point that it was fair to wonder whether the Phillies understood what it took to be an elite ballclub. Through his actions and decisions, he was telling them that something was wrong, that something had to change, and he doubted that it would.

It eventually did. That doubt has dissipated over time. Citizens Bank Park became a draw and a revenue booster. Charlie Manuel, Pat Gillick, and the core of those 2007-11 teams came along. John Middleton is now a junior George Steinbrenner, willing to spend whatever he deems necessary to get his bleeping trophy back.

Rolen will soon be inducted into the Phillies Wall of Fame, and he’ll be back in Philadelphia on Sept. 22 to celebrate. Anyone inclined to boo him that night ought to keep quiet. Scott Rolen is in, and he should be in, and he’s not the bad guy anymore, if he ever was.